A week or so ago, I wrote about the books (specifically novels) that I can’t seem to finish despite beginning them five, six, seven plus times. In that post, I noted that there “are certain books I’ll probably never ‘finish,’ that I have no aim of finishing,” and hence didn’t include in my silly little list. Such titles seemed to need their own post.

“Finish” is probably the wrong verb to use to denote the act of reading, in traditional sequence, all the words on all the pages of a grand great novel. I have never really “finished” the books that I’ve read the most times from cover to cover—books like Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Their Eyes Were Watching God, Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Blood Meridian, 2666. Something about such books remains somewhere inside of me, unfinished (in contrast to the many, many novels—most often contemporary “literary” fictions—that I truly finish by reading and then jettisoning from memory). The great books that I’ve finished are unfinished. Something of the really great novels wriggles around in the background of consciousness, whispering, howling.

Putting together a little list of books I’m always reading but will likely never finish was not difficult, although I should clarify that I’ve intentionally left off a good number of critical texts—stuff like Derrida, Foucault, Kristeva, etc.—as well as the letters, notebooks, and journals of writers that I return to again and again. I tried to stick to novels. But are the works pictured/listed here—Tristram Shandy, The Anatomy of Melancholy, Don Quixote, Finnegans Wake, and 1982, Janine—are these actually novels? The question is complex and productive, but I’ll answer it with the simple, “Yes, but– ”

(And yet, parenthetically: That the novelness of these novels is suspect is perhaps a key to why these are the works that fascinate me, that these unnovelly novels make me stumble; I resort to shelving them, grab for critical interpretations, guides, commentaries, etc.—in the hopes of…of what?)

Joyce’s Finnnegans Wake is a nice starting place for this little list. The novel’s famous opening line (“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs”) actually completes the novel’s “final” (non-)sentence (“A lone a last a loved a long the”). So Finnegans Wake is a loop, an infinite jest. Over the past decade, I’ve dipped into the book again and again, using Joseph Campbell’s Skeleton Key as a friendly guide. I’ve learned to have fun with Finnegans Wake, taking something from its language, its connections, its syntheses, while abandoning the pretense that I’ve anything to gain by trucking through it at full speed just to “finish” it.

I pick up Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman less often than I used to, having recovered from trying to understand it. The novel seems to me proof that the term “postmodern” is simply a description of a way of seeing, and not a set of aesthetic conditions. Also, I love that Sterne loves the dash—

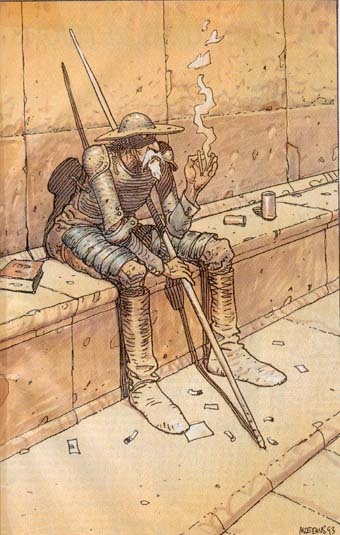

It’s perhaps a great moral failing on my part that I’ve never made it past the first few chapters of the Second Part of Don Quixote. I’m familiar with it, largely by way of Nabokov’s lectures and summaries. Anyway, I fail to understand Don Quixote; I fail to read it rightly.

Alasdair Gray’s 1982, Janine doesn’t have the same reputation as the other novels I’ve listed here; its inclusion wasn’t so much an afterthought but a realization—I bought it four years ago and have yet to shelve it. It’s always on a coffee table, the edge of a sofa, next to my bed, cooing, Start again. I start reading it and then I skip ahead to its weird black heart, then I read from the end, then I go back to the beginning. Then I put it aside, having made no “progress.”

I don’t know what Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy is. Is it a novel? (Wait. I think we went through this above). I first encountered it as a bewildered undergrad, checking out an old huge hardback edition from the library. I made a small dent (aided by Ritalin). All that Latin is Greek to me. In his preface to the NYRB edition, William H. Gass advises, “Be prepared to proceed slowly and you will soon go swiftly enough. Read a member a day; it will chase gloom away.” I have not read a member a day, but I do like to pull Melancholy from the shelf late at night, after a few glasses of wine, and dip into it somewhere. I will never finish it.

And yet I’ve retained more from these unfinished novels than most of the contemporary fiction novels I’ve read. Anna Livia Plurabelle. The priest burning poor Quixote’s beautiful books. The marbled pages, the blacked out pages, the squiggles of Tristram Shandy. The typographic explosions in 1982, Janine. The dirty bits. The lists. The force of language, above all.

In a sense, not “finishing” these grand weird novels keeps them vital to me, present somehow, promising in their possibility, taunting and tantalizing in their pregnant unfinishabilty.