Mike Watt and Adam Harvey adapted the “Shem the Penman” episode of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake for the Waywords and Meansigns project. Raymond Pettibon provided an illustration.

Tag: Punk Rock

Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (Book Acquired, 11.18.2014)

This one looks pretty good: Viv Albertine’s memoir Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. U.S. publisher St. Martin’s Press’s blurb:

Viv Albertine is a pioneer. As lead guitarist and songwriter for the seminal band The Slits, she influenced a future generation of artists including Kurt Cobain and Carrie Brownstein. She formed a band with Sid Vicious and was there the night he met Nancy Spungeon. She tempted Johnny Thunders…toured America with the Clash…dated Mick Jones…and inspired the classic Clash anthem “Train in Vain.” But Albertine was no mere muse. In Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys., Albertine delivers a unique and unfiltered look at a traditionally male-dominated scene.

Her story is so much more than a music memoir. Albertine’s narrative is nothing less than a fierce correspondence from a life on the fringes of culture. The author recalls rebelling from conformity and patriarchal society ever since her days as an adolescent girl in the same London suburb of Muswell Hill where the Kinks formed. With brash honesty—and an unforgiving memory—Albertine writes of immersing herself into punk culture among the likes of the Sex Pistols and the Buzzcocks. Of her devastation when the Slits broke up and her reinvention as a director and screenwriter. Or abortion, marriage, motherhood, and surviving cancer. Navigating infidelity and negotiating divorce. And launching her recent comeback as a solo artist with her debut album, The Vermilion Border.

Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. is a raw chronicle of music, fashion, love, sex, feminism, and more that connects the early days of punk to the Riot Grrl movement and beyond. But even more profoundly, Viv Albertine’s remarkable memoir is the story of an empowered woman staying true to herself and making it on her own in the modern world.

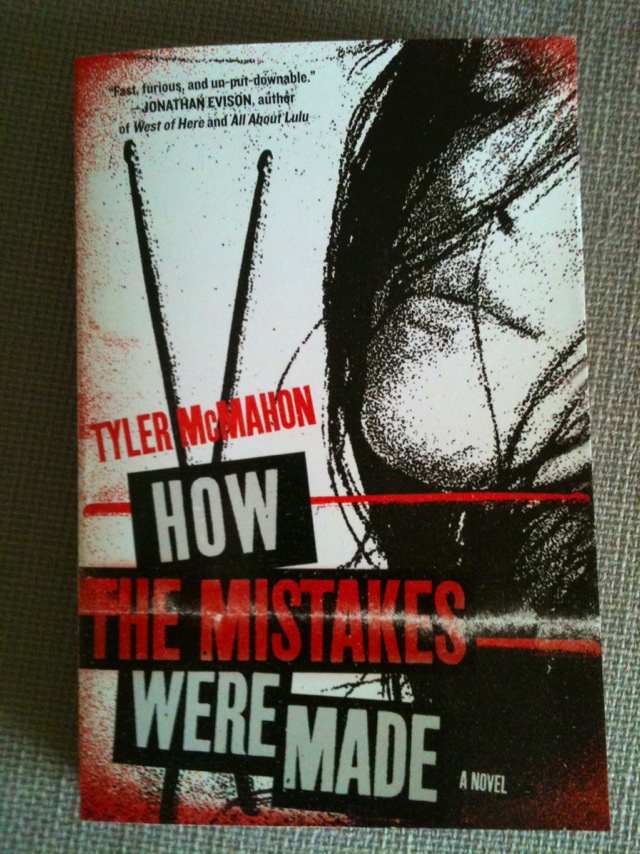

Book Acquired, 10.29.2011

How the Mistakes Were Made, a novel by Tyler McMahon. Description from the author’s site—

Laura Loss came of age in the hardcore punk scene of the 1980s, the jailbait bassist in her brother Anthony’s band. But a decade after tragedy destroyed Anthony and their iconic group, she finds herself serving coffee in Seattle.

While on a reluctant tour through Montana, she meets Sean and Nathan, two talented young musicians dying to leave their small mountain town. Nathan proves to be a charismatic songsmith. Sean has a neurological condition known as synesthesia, which makes him a genius on lead guitar. With Laura’s guidance, the three of them become the Mistakes—accidental standard-bearers for the burgeoning “Seattle Sound.”

As the band graduates from old vans and darkened bars to tour-buses and stadiums, there’s no time to wonder whether stardom is something they want—or can handle. At the height of their fame, the volatile bonds between the three explode in a toxic cloud of love and betrayal. The world blames Laura for the band’s demise. Hated by the fans she’s spent her life serving, she finally tells her side of how the Mistakes were made.

Book trailer—

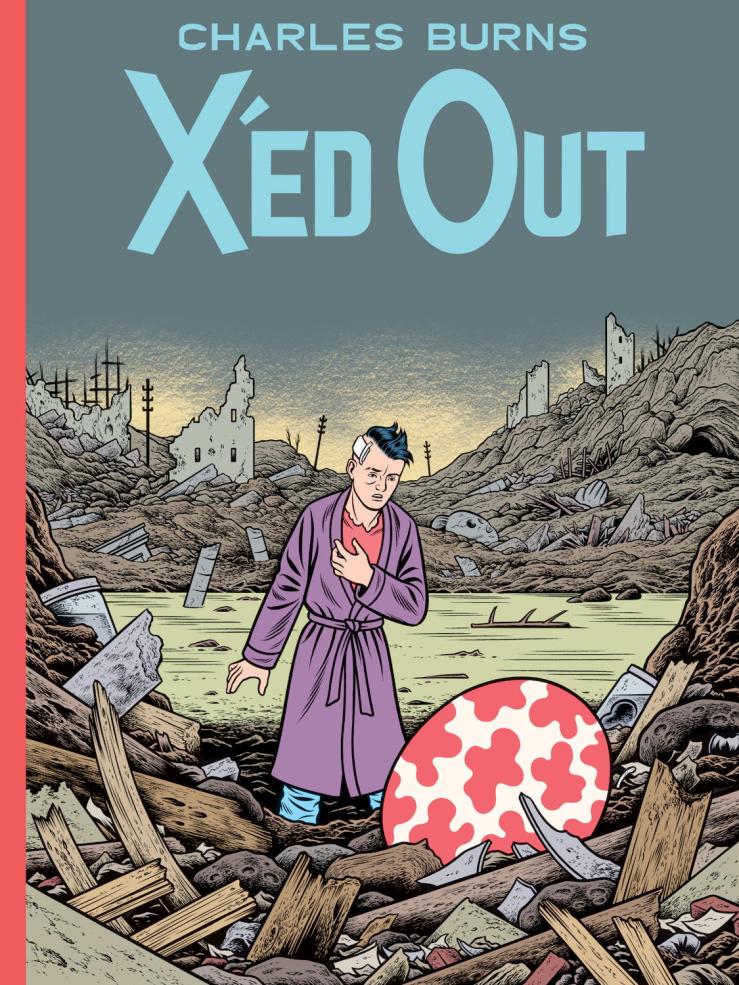

X’ed Out — Charles Burns

If you like Charles Burns, go ahead and pick up X’ed Out, the first (and very promising) entry in a new trilogy. Skip this review. You’ll probably be happier (and more unsettled) just experiencing all that vivid, glorious weirdness for yourself without any potential spoilers. If you need convincing, read on.

X’ed Out begins in a strange fever-dreamland that doesn’t immediately announce itself as such. Instead, we tentatively enter this weird world with Doug, the book’s protagonist, who, like Alice following the white rabbit, chases his (long dead) childhood cat through a crack in the wall. Doug traverses a cavernous, ruinous place, littered with murky detritus and swamped in a strange flood, to finally arrive in a bizarre desert town that approximates William Burroughs’s Interzone. Populated by mean lizards who dress like Mormon slackers and other grubby grotesques, the terrain readily recalls both Tatooine and Asian bazaars. Hapless Doug, still in pajamas, house coat, and slippers — and marked by an as-yet-unexplained head wound — soon finds himself under the guidance of a strange little diapered dwarf, who may or may not have his best interest in mind. The dreamworld unravels as Doug glances an old man — an “oldie,” as the dwarf says — who we will learn later is Doug’s father. An all of a sudden we’re back in the real world, back in waking life.

But no. That’s not right. Not “back” — we were never in the waking world to begin with. Significantly, X’ed Out begins in the Burroughsian dreamworld and then moves to a conscious, concrete reality. Burns’s dreamworld sequences explicitly reference Belgian cartoonist Hergé’s seminal Tintin comics (you can see how X’ed Out’s cover riffs on the Tintin adventure The Shooting Star here). Doug’s dream face is an expressive, stark mask, a naïve, cartoonish contrast to the bizarre nightmare to which it reacts.

Doug — the waking world Doug, the “real” Doug, that is — pulls a similar mask over his more realistically drawn face later in the story when he does his “Burroughs thing” at a slummy art punk party. Alienated from the scenesters who don’t get his cut-up poetry performance, Doug takes up with Sarah, a girl from his photography class with a thing for razor blades and pig hearts. The same night they meet, he loses his girlfriend, and her crazy boyfriend goes to jail for assaulting a cop. They initiate their romance in Patti Smith records, lines of cocaine, and sick Polaroids. Ah, young love.

But all of that is in another kind of dreamworld, the past, a retreat for the “real,” contemporary Doug, who spends his few waking hours cringing in his bathrobe, poring over old photos, and eating the occasional Pop Tart. At night he eats pain pills and goes to Interzone-land, a place that seems as real and solid and valid as his past with Sarah, a past he has apparently lost. Doug bears a huge patch over half his head (significantly x-shaped in his Interzone version), and both this wound as well as the psychic trauma he’s obviously endured (and is enduring) remain unexplained throughout X’ed Out. However, Burns’s often-grisly images hint repeatedly at a past event filled with violence and loss. X’ed Out leaves us in the Interzone, with the dwarf making long-term plans for Tintinized Doug. There’s even talk of establishing residency and employment–it feels like Doug is here to stay (at least in his non-waking hours). X’ed Out ends maddeningly with a girl who visually recalls Sarah being borne by lizard men to a giant hive. The dwarf explains that she is their new queen–and like some insect queen, she is a breeder. Yuck. The ending is the biggest problem with X’ed Out, simply because it leaves one stranded, wanting more weirdness.

In Black Hole, Burns established himself as a master illustrator and a gifted storyteller, using severe black and white contrast to evoke that tale’s terrible pain and pathos. X’ed Out appropriately brings rich, complex color to Burns’s method, and the book’s oversized dimensions showcase the art beautifully. This is a gorgeous book, both attractive and repulsive (much like Freud’s concept of “the uncanny,” which is very much at work in Burns’s plot). Like I said at the top, fans of Burns’s comix likely already know they want to read X’ed Out; weirdos who love Burroughs and Ballard and other great ghastly fiction will also wish to take note. Highly recommended.

X’ed Out is available in hardback from Pantheon on October 19th, 2010.

End of the Century–The Heartbreaking Story of the Ramones

If you love the Ramones, you really shouldn’t watch the 2003 documentary film End of the Century–it will only break your heart.

I love the Ramones; I’ve loved the Ramones since I was a kid. I was lucky enough to see them in concert about twelve years ago (even then we were hip to the fact that the Ramones without Dee Dee–the C.J. version of Ramones–was not really the real Ramones). My favorite memory of the show was Joey saying that the venue of the show was built on top of a pet cemetery. Then they played “Pet Cemetery.” Genius.

So well and anyway. End of the Century. This is an excellent music documentary, a standout in a genre which is generally hit or miss. Unlike weaker films that rely on narrators or musicians influenced by the subject*, End of the Century is composed entirely of interviews (both archival and original to the film) with the Ramones themselves (Dee Dee, Tommy, Joey, Johnny, Marky, Richie (Richie wears a conservative suit in his interview, and mostly complains about not getting a taste of “that T-shirt money”) and C.J. (C.J. comes across as naive, energetic, and wholly endearing, making me feel kind of bad about my previous opinions of him). In addition to the Ramones’ first-hand accounts, there are plenty of interviews with managers and friends and family and roadies and so on–eyewitnesses who candidly relate the good, the bad, and the ugly in excruciating detail (there is plenty of ugly). Raw live footage dating back to the early 70s brings to life the sheer volume and bizarre intensity of a Ramones show.

So why so heartbreaking? Well, here’s the deal. We know that the John and Paul didn’t like each other. We know that Mick and Keith bicker. We know that bands have “creative differences” and egos get bruised and so and so on. But with the Ramones, well, I guess I always thought of them, as well, cartoons of themselves. But End of the Century makes it very clear that these guys were very, very serious about themselves and what they did. They were in no way cultivating an image: the Ramones really were what you thought they were. And they hated each other. Like, years-of-not-talking-to-each-other hatred, right up until their retirement. They were bitter–they really wanted to be successful. Now, I always thought of the Ramones as legendary, as huge, as the original punk band. But they wanted to be huge, huge like the Beach Boys or the Beatles. Hits on the radio huge (a quick aside: the accounts of working with Phil Spector on the 1980 album End of the Century, in the hopes of gaining a top 10 hit, are hilarious. Apparently Phil held the band plus entourage at gunpoint, threatening to shoot them if they returned to the hotel. The reason for Phil’s hostage-taking: he wanted them to hang out and watch movies. But I’m sure Spector’s like, totally not guilty of murdering that chick in his house). So a lot of the movie is the Ramones lamenting that they “never made it” (again, to me this was ludicrous). But really it’s the hatred, the meanness of their interviews, their complete dismissal of each other that I found most disconcerting (particularly heartbreaking is hearing Johnny’s non-affected nonchalance over Joey’s relatively recent (to the time of the movie’s shooting) death from lymphoma). Maybe I’m just a foolish fan who wanted my cartoons.

The film ends by noting that Dee Dee died of a heroin overdose two months after the film finished shooting. Johnny Ramone died in 2004. The principal members of the band all died within a few short years of each other, like married folks often do.

To end on a lighter note, check out this footage from the film, featuring Dee Dee’s rap project, Dee Dee King’s “Funky Man” (listen for this embarrassing nugget: “I’m a Negro too!”)

* There are one or two very brief interviews (like one or two sentences) with famous fans, including, of course, Thurston Moore, who is contractually obligated to appear in any film about any musician. Check out his prolific (and incomplete–unless my memory fails me he’s also in the 1995 Brian Wilson documentary I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times) filmography here.