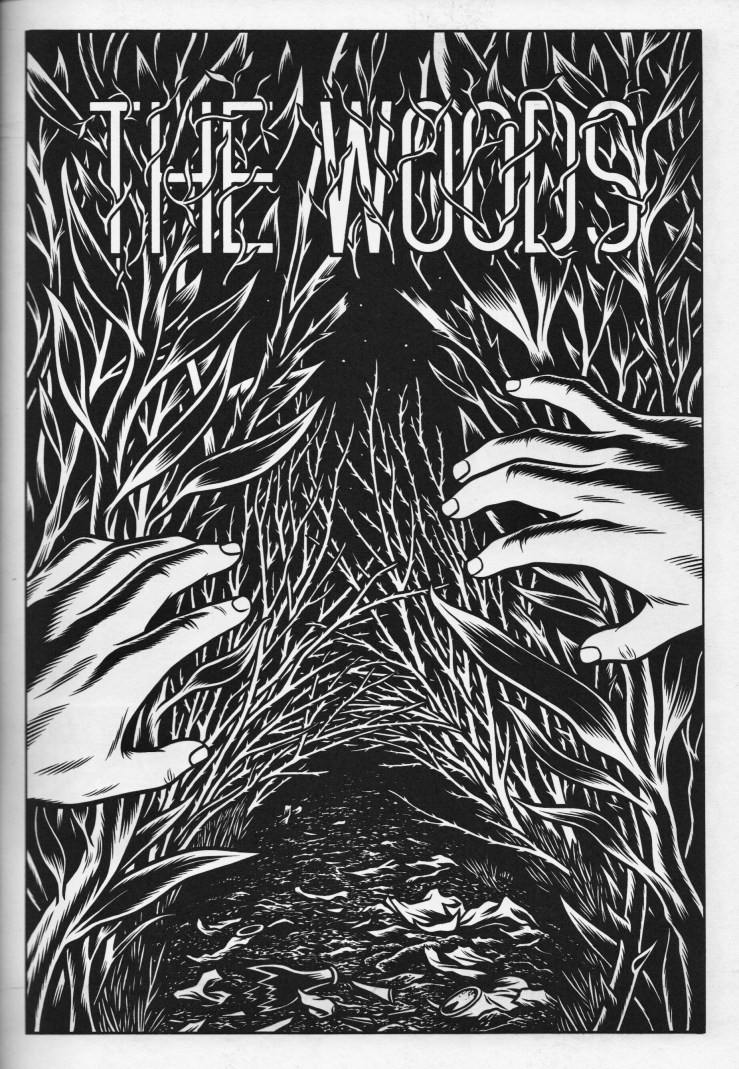

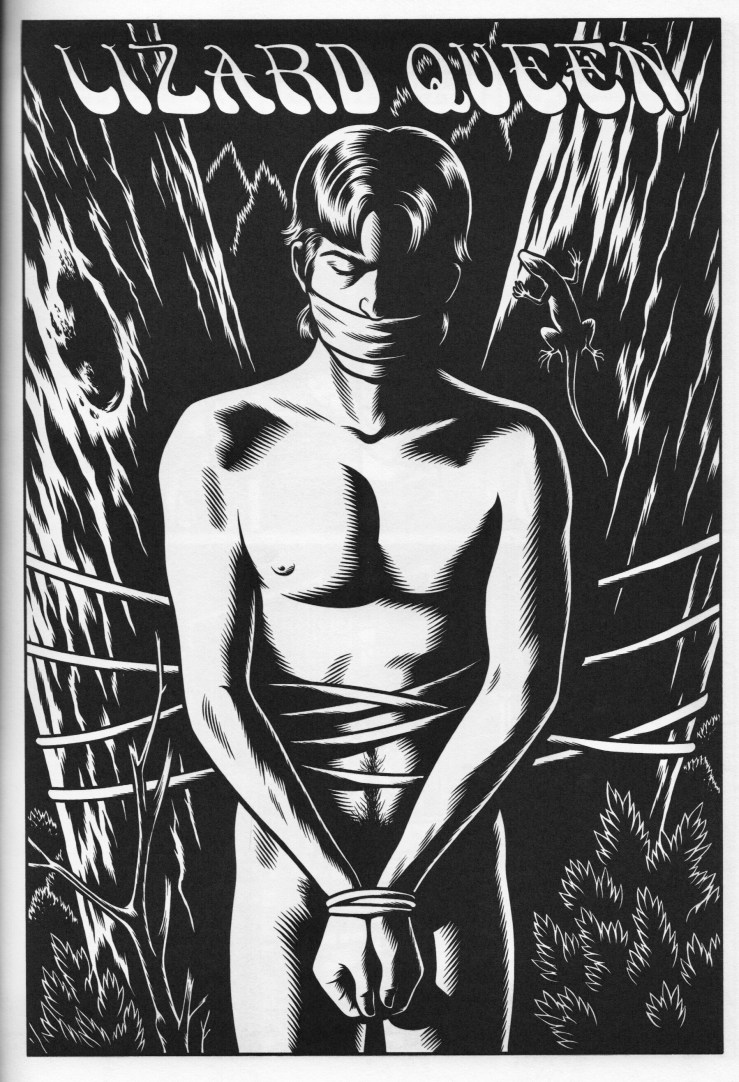

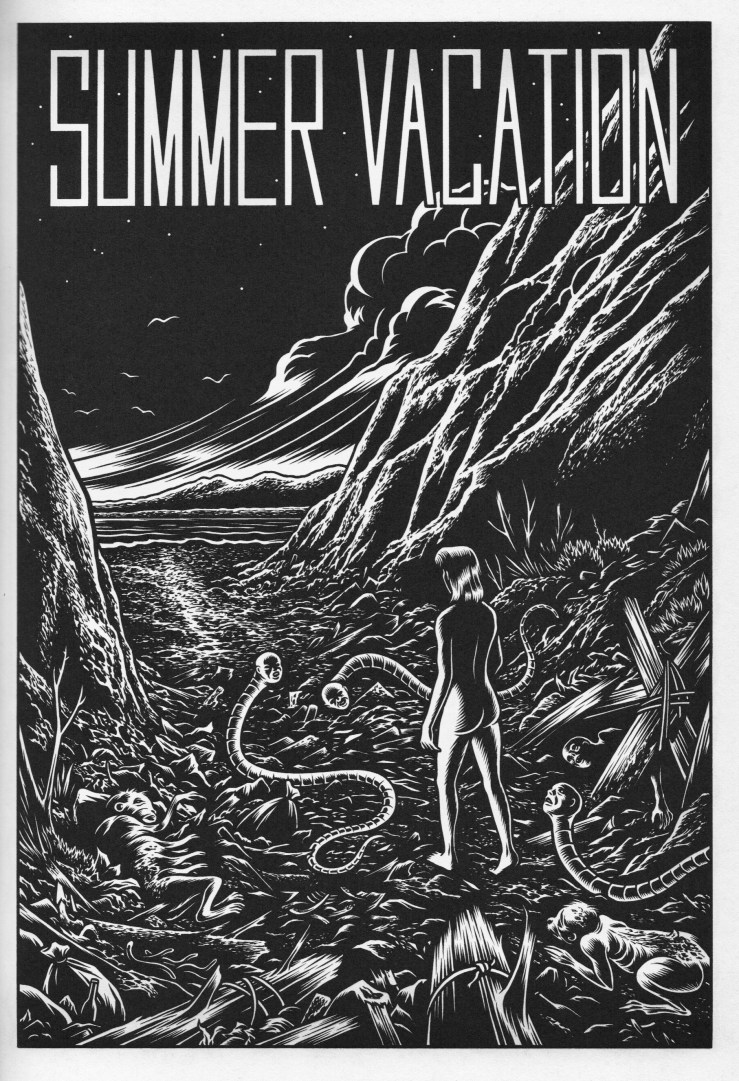

With Halloween approaching, here are three creepy full page panels from Charles Burns’s Black Hole (Pantheon, 2005).

Tag: Black Hole

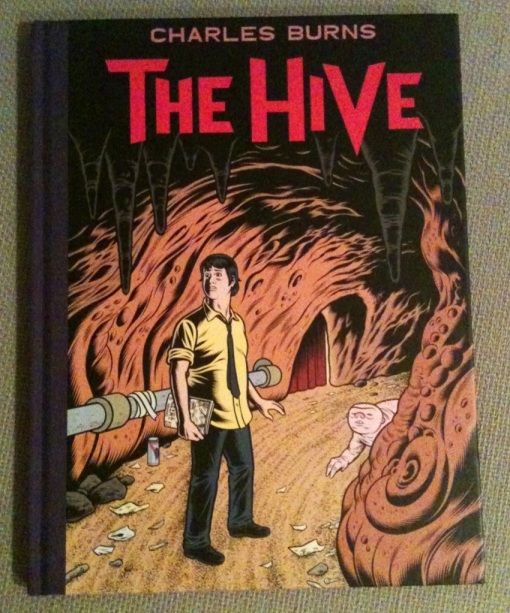

Charles Burns Enriches His Wonderfully Weird Trilogy with The Hive

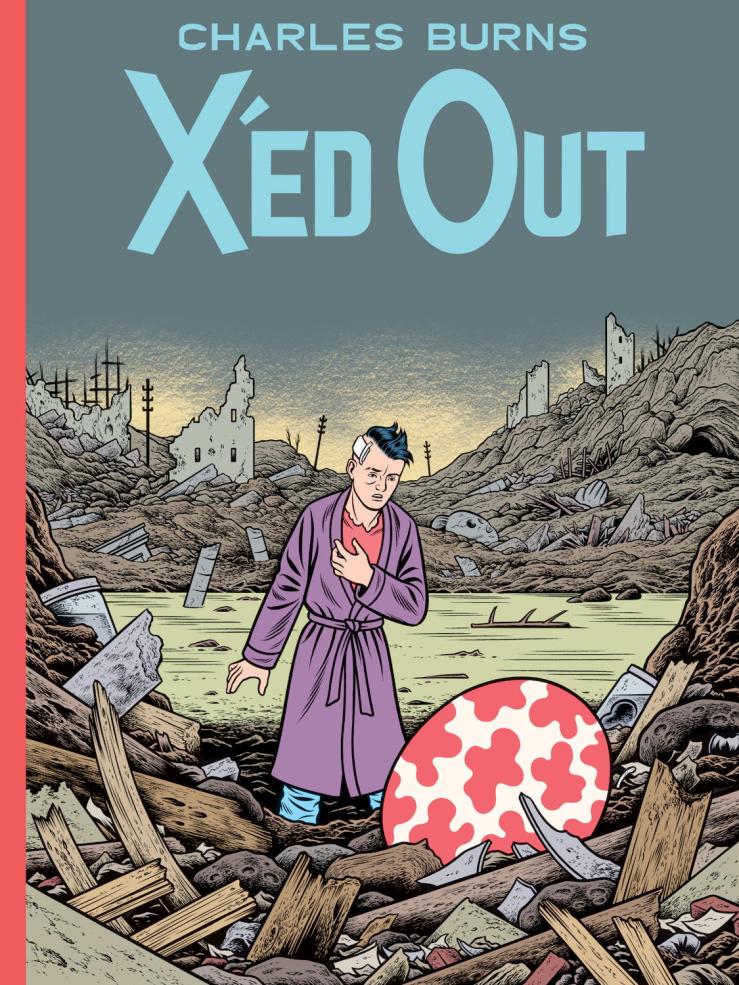

In X’ed Out, Charles Burns created a rich and strangely layered world focusing on Doug, a confused and injured young man. In his parents’ suburban basement, Doug parcels out the last of his late father’s painkillers, slipping from haunted memories of his relationship with Sarah into fevered nightmares of abject horror and then into a wholly other world, a realm that recalls William Burroughs’s Interzone. In this alien world, Doug takes on the features of Nitnit (an inversion of Tintin), the alter-ego he adopts when performing spoken word cut-ups as the opening act for local punk rock bands. What made X’ed Out so compelling (apart from Burns’s thick, precise illustration, of course), was the sense that this Interzone was a reality equal to Doug’s own “real world” — that it was somehow more real than Doug’s dreams.

The Hive (part two of the proposed trilogy) deepens the richness and complexity of the world Burns has imagined. The title refers to a location in Interzone. Doug (or Nitnit) has found employment in The Hive as a kind of mail clerk or janitor. His primary role though is secret librarian, catering to the reading needs of the breeders of The Hive. One breeder seems to be a version of Doug’s ex-girlfriend; the other is a double of Sarah, who asks Doug/Nitnit to bring her romance comics—which he does—only he skips a few issues. These missing issues stand in for the information Doug (and Burns) withholds from the reader, the missing fragments that have been x’ed out.

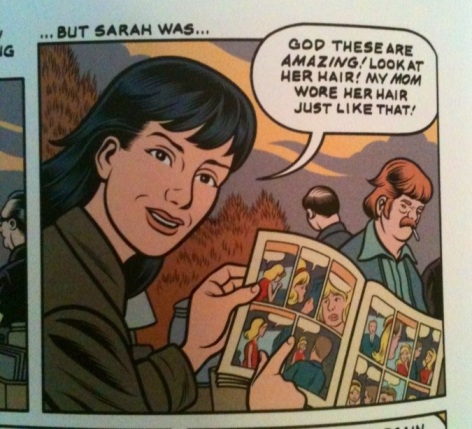

Burns uses romance comics as a framing or organizing device, a motif linking the disparate worlds of his narrative. In the “real world” — which is to say the world of Doug’s memory — we learn that he buys a stack of old romance comics for Sarah on their first date.

Throughout the narrative, Burns plays his characters against the extreme, often hysterical dramas of 1950s and ’60s romance comics; his strong lines and heavy inks readily recall the early works of Simon and Kirby, but more precise and careful—something closer to Roy Lichtenstein, only more sincere, more emotional.

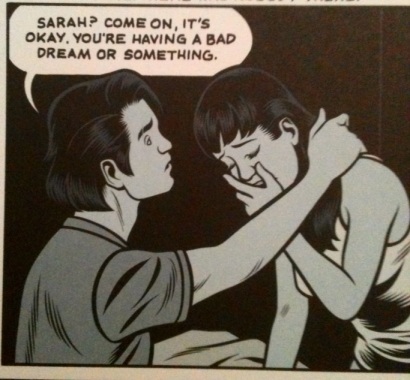

In The Hive, we learn more about Doug’s troubled relationship with Sarah, who has problems out the proverbial yingyang (not the least of which is a violent psychopathic ex-boyfriend).

Burns weaves the story of Sarah and Doug’s relationship into the fallout of Doug’s father’s death—a death Doug was completely shuttered to, we realize. Doug’s drug-dreams dramatize the missing pieces of these narratives, and the Interzone set-pieces propel the mystery aspects of the narrative forward, as Doug’s alter-ego plumbs the detritus of his psychic fallout. Through the metatextual motif of reading-comic-books-as-detective-works, Burns explores themes of trauma, abjection, and distance. Images of pigs and cats, freaks and punks, portals and holes litter The Hive.

Burns has always been a perfectionist of dark lines and strange visions, and his last full graphic novel Black Hole was a triumph of atmosphere and mood. With the first two entries of his trilogy, however, Burns has showed a significant maturation in storytelling, characterization, and dialogue. I often thought parts of Black Hole seemed forced or rushed (no doubt because Burns faced daunting production troubles during the decade he worked on the novel—including his original publisher Kitchen Sink folding). With X’ed Out and now The Hive we can see a more patient artist, working out an emotionally complex and compelling story in rich, symbolic layers.

I reread X’ed Out and then read The Hive in one greedy sitting; then I went through The Hive again, more slowly, more attendant to its details and nuances. We had to wait two years between X’ed Out and The Hive—and it was worth the two year wait. So if we must wait another two years—or more—for the final entry, Sugar Skull, so be it.

Charles Burns’s The Hive (Book Acquired 10.15.2012)

For some reason—some reason founded on no reason at all but rather superstitious suspicion—I didn’t believe Charles Burns would follow up X’ed Out, the first chapter of a proposed trilogy. I suppose X’ed Out had unresolved cult classic written all over it (written metaphorically, of course).

X’ed Out was one of my favorite books of 2010. From my review:

In Black Hole, Burns established himself as a master illustrator and a gifted storyteller, using severe black and white contrast to evoke that tale’s terrible pain and pathos. X’ed Out appropriately brings rich, complex color to Burns’s method, and the book’s oversized dimensions showcase the art beautifully. This is a gorgeous book, both attractive and repulsive (much like Freud’s concept of “the uncanny,” which is very much at work in Burns’s plot). Like I said at the top, fans of Burns’s comix likely already know they want to read X’ed Out; weirdos who love Burroughs and Ballard and other great ghastly fiction will also wish to take note. Highly recommended.

So, of course I was stoked when Burns’s sequel The Hive showed up a few weeks ago—in fact, the only thing that got in the way of me reading it immediately was that it showed up in a package along with Chris Ware’s Building Stories (this is, without question, the best package I’ve received in six years of doing the blog).

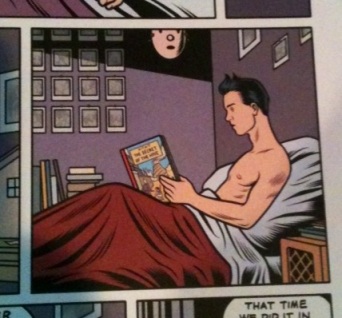

Anyway, I’ll be revisiting X’ed Out and then reviewing The Hive in the next week or so. For now, a few pics. Two from the interior above. And our hero Doug, in his alter-ego/costume Nitnit (inverse Tintin):

I dig this panel in particular: A take on Roy Lichtenstein via Raymond Pettibon via the romance comics those pop artists were riffing on:

The AV Club Interviews Charles Burns

The AV Club’s Sam Adams interviews Charles Burns about Tintin, Burroughs, why he’s not involved in making the Black Hole movie, 1977, why he had to change how he colored his art, and his new book, X’ed Out. There’s also this nugget (we’d been wondering)–

The AV Club’s Sam Adams interviews Charles Burns about Tintin, Burroughs, why he’s not involved in making the Black Hole movie, 1977, why he had to change how he colored his art, and his new book, X’ed Out. There’s also this nugget (we’d been wondering)–

AVC: Is the completed three-volume work going to be called X’ed Out?

CB: They’re all going to be different stories. So for the next one, it says “Next: The Hive.” So the next book is called The Hive.

AVC: Is there a name for the trilogy?

CB: No, not in my mind.

Charles Burns Interviewed

Vodpod videos no longer available.

Charles Burns Annotates a Page from X’ed Out

At New York Magazine, Charles Burns annotates a page from his excellent new graphic novel X’ed Out. See the slideshow here. A sample–

X’ed Out — Charles Burns

If you like Charles Burns, go ahead and pick up X’ed Out, the first (and very promising) entry in a new trilogy. Skip this review. You’ll probably be happier (and more unsettled) just experiencing all that vivid, glorious weirdness for yourself without any potential spoilers. If you need convincing, read on.

X’ed Out begins in a strange fever-dreamland that doesn’t immediately announce itself as such. Instead, we tentatively enter this weird world with Doug, the book’s protagonist, who, like Alice following the white rabbit, chases his (long dead) childhood cat through a crack in the wall. Doug traverses a cavernous, ruinous place, littered with murky detritus and swamped in a strange flood, to finally arrive in a bizarre desert town that approximates William Burroughs’s Interzone. Populated by mean lizards who dress like Mormon slackers and other grubby grotesques, the terrain readily recalls both Tatooine and Asian bazaars. Hapless Doug, still in pajamas, house coat, and slippers — and marked by an as-yet-unexplained head wound — soon finds himself under the guidance of a strange little diapered dwarf, who may or may not have his best interest in mind. The dreamworld unravels as Doug glances an old man — an “oldie,” as the dwarf says — who we will learn later is Doug’s father. An all of a sudden we’re back in the real world, back in waking life.

But no. That’s not right. Not “back” — we were never in the waking world to begin with. Significantly, X’ed Out begins in the Burroughsian dreamworld and then moves to a conscious, concrete reality. Burns’s dreamworld sequences explicitly reference Belgian cartoonist Hergé’s seminal Tintin comics (you can see how X’ed Out’s cover riffs on the Tintin adventure The Shooting Star here). Doug’s dream face is an expressive, stark mask, a naïve, cartoonish contrast to the bizarre nightmare to which it reacts.

Doug — the waking world Doug, the “real” Doug, that is — pulls a similar mask over his more realistically drawn face later in the story when he does his “Burroughs thing” at a slummy art punk party. Alienated from the scenesters who don’t get his cut-up poetry performance, Doug takes up with Sarah, a girl from his photography class with a thing for razor blades and pig hearts. The same night they meet, he loses his girlfriend, and her crazy boyfriend goes to jail for assaulting a cop. They initiate their romance in Patti Smith records, lines of cocaine, and sick Polaroids. Ah, young love.

But all of that is in another kind of dreamworld, the past, a retreat for the “real,” contemporary Doug, who spends his few waking hours cringing in his bathrobe, poring over old photos, and eating the occasional Pop Tart. At night he eats pain pills and goes to Interzone-land, a place that seems as real and solid and valid as his past with Sarah, a past he has apparently lost. Doug bears a huge patch over half his head (significantly x-shaped in his Interzone version), and both this wound as well as the psychic trauma he’s obviously endured (and is enduring) remain unexplained throughout X’ed Out. However, Burns’s often-grisly images hint repeatedly at a past event filled with violence and loss. X’ed Out leaves us in the Interzone, with the dwarf making long-term plans for Tintinized Doug. There’s even talk of establishing residency and employment–it feels like Doug is here to stay (at least in his non-waking hours). X’ed Out ends maddeningly with a girl who visually recalls Sarah being borne by lizard men to a giant hive. The dwarf explains that she is their new queen–and like some insect queen, she is a breeder. Yuck. The ending is the biggest problem with X’ed Out, simply because it leaves one stranded, wanting more weirdness.

In Black Hole, Burns established himself as a master illustrator and a gifted storyteller, using severe black and white contrast to evoke that tale’s terrible pain and pathos. X’ed Out appropriately brings rich, complex color to Burns’s method, and the book’s oversized dimensions showcase the art beautifully. This is a gorgeous book, both attractive and repulsive (much like Freud’s concept of “the uncanny,” which is very much at work in Burns’s plot). Like I said at the top, fans of Burns’s comix likely already know they want to read X’ed Out; weirdos who love Burroughs and Ballard and other great ghastly fiction will also wish to take note. Highly recommended.

X’ed Out is available in hardback from Pantheon on October 19th, 2010.