The Magpie on the Gallows, 1568 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569)

The Magpie on the Gallows, 1568 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569)

“Haymaking”

by

William Carlos Williams

The living quality of

the man’s mind

stands out

and its covert assertions

for art, art, art!

painting

that the Renaissance

tried to absorb

but

it remained a wheat field

over which the

wind played

men with scythes tumbling

the wheat in

rows

the gleaners already busy

it was his own—

magpies

the patient horses no one

could take that

from him

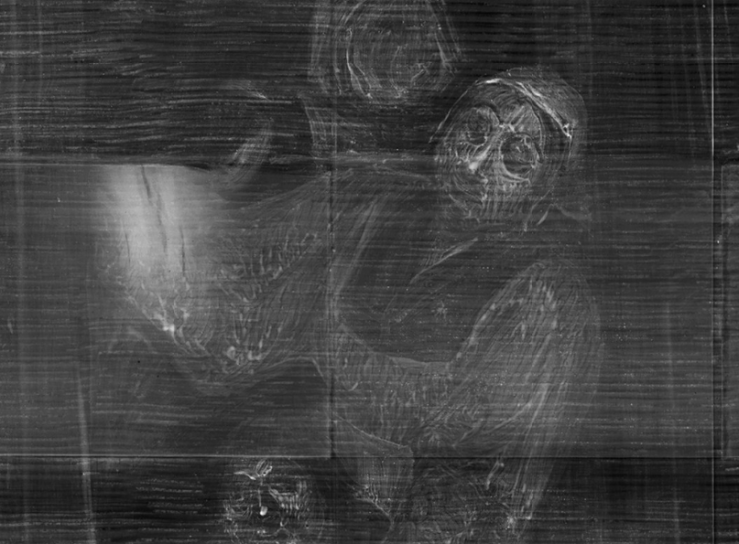

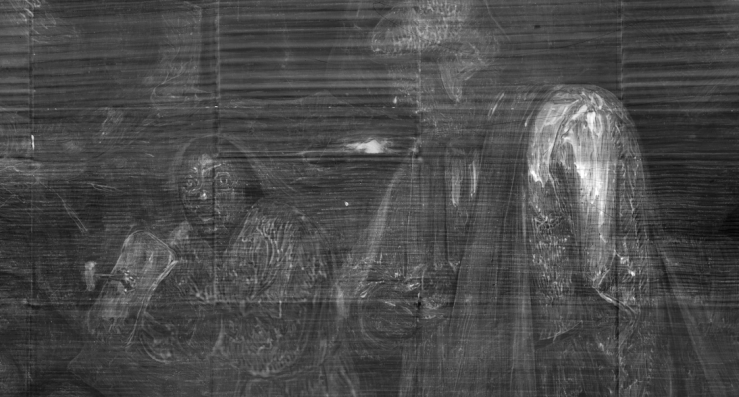

X-radiographic details from The Battle Between Carnival and Lent (1559) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c 1525/30–1569). From Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna’s marvelous feature Inside Breugel.

Twelve Proverbs, c.1560 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder Original

“Breughel”

by

Aldous Huxley

from Along the Road, 1925

Most of our mistakes are fundamentally grammatical. We create our own difficulties by employing an inadequate language to describe facts. Thus, to take one example, we are constantly giving the same name to more than one thing, and more than one name to the same thing. The results, when we come to argue, are deplorable. For we are using a language which does not adequately describe the things about which we are arguing.

The word “painter” is one of those names whose indiscriminate application has led to the worst results. All those who, for whatever reason and with whatever intentions, put brushes to canvas and make pictures, are called without distinction, painters. Deceived by the uniqueness of the name, aestheticians have tried to make us believe that there is a single painter-psychology, a single function of painting, a single standard of criticism. Fashion changes and the views of art critics with it. At the present time it is fashionable to believe in form to the exclusion of subject. Young people almost swoon away with excess of aesthetic emotion before a Matisse. Two generations ago they would have been wiping their eyes before the latest Landseer. (Ah, those more than human, those positively Christ-like dogs—how they moved, what lessons they taught! There had been no religious painting like Landseer’s since Carlo Dolci died.)

These historical considerations should make us chary of believing too exclusively in any single theory of art. One kind of painting, one set of ideas are fashionable at any given moment. They are made the basis of a theory which condemns all other kinds of painting and all preceding critical theories. The process constantly repeats itself. Continue reading ““Breughel” — Aldous Huxley”

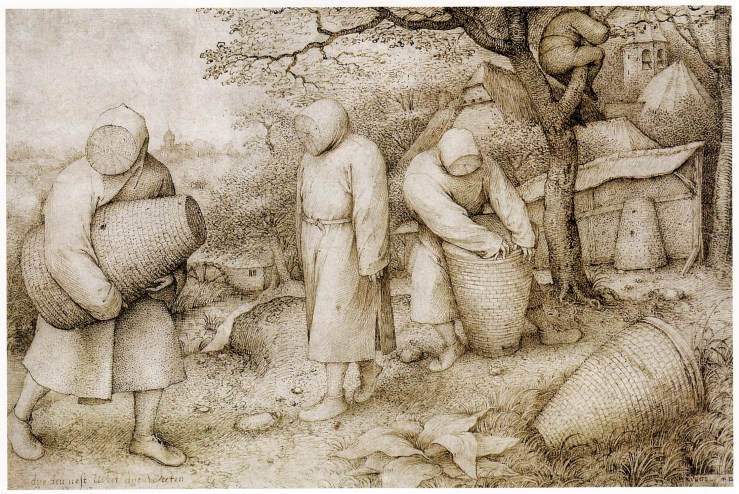

The Peasant and the Birdnester, 1568 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569)

William Carlos Williams’ final and posthumous book Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems (1962) opens with a cycle of ten ekphrastic poems that describe (and subtly interpret) ten paintings by the sixteenth-century Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

These poems are, in my estimation, some of Williams’ finest. Possibly the most famous of these poems is “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” a devastating observation of how inclined we are to look away from miracles.

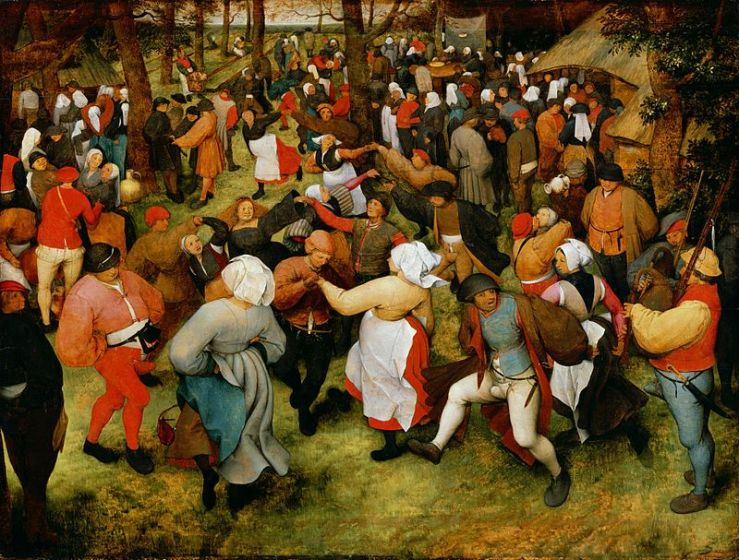

Another of Williams’ Brueghel poems, “The Dance,” which takes The Peasant Dance as its subject, is also widely-anthologized; however Williams’ poem “The Dance” was published in The Wedge (1944). Williams’ “The Dance,” which begins “In Breughel’s great picture, The Kermess, / the dancers go round,” is frequently and incorrectly cited to have been published in Pictures from Brueghel (a cursory internet search shows this misinformation appears in Harper’s, as well as the last resort of lazy high school students, Shmoop). Williams did publish a poem called “The Dance” in Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems, but this “Dance” is very much one of those other poems (this “Dance” begins “When the snow falls the flakes / spin upon the long axis,” for the record). That The Peasant Wedding is another subject of Pictures of Brueghel may also account for the spread of this misinformation (which can be resolved simply by opening the second volume of The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, which includes both The Wedge and Brueghel). But I find myself going on a bit too much about this simple mistake.

Let’s get to the poem:

“The Wedding Dance in the Open Air”

by

William Carlos Williams

Disciplined by the artist

to go round

& roundin holiday gear

a riotously gay rabble of

peasants and theirample-bottomed doxies

fills

the market squarefeatured by the women in

their starched

white headgearthey prance or go openly

toward the wood’s

edgesround and around in

rough shoes and

farm breechesmouths agape

Oya !

kicking up their heels

“The Wedding Dance in the Open Air” echoes the sensual depth of Williams’ earlier poem “The Dance” (1944), which emphasized the hips and bellies and shanks of those dancers who are “swinging their butts” (!) to “the squeal and the blare and the / tweedle of bagpipes” as they prance about.

The word “prance” is repeated too in “Wedding Dance” — and not only do our partygoers prance, they even “go openly / toward the wood’s / edges,” the edge of civilization where civilization gets made.

At the other edge of the painting, the foreground, are some of the boldest of Williams’ “riotously gay rabble.” But should I call them “Williams’ ‘riotously gay rabble'” or Brueghel’s? I think that it is Williams’ interpretation that matters here, but Brueghel gives him the material with which to grapple.

Look at those colors, look at those codpieces! Look at the hands, twisting, gripping, artfully fingering!

Williams captures the painting’s sexual energy not just in lines that highlight the “ample-bottomed doxies” who fill this market square, but also in the vivacious images of “mouths agape” and heels a’ kicking. The poem pulses with an energy proximal to the painting, an energy simultaneously alien and native, highlighting not only the difference in the two art forms—poetry and painting—but also the space between the viewer and the thing being viewed.

Enhancing the poem’s ekphrastic powers of imagery and feeling are the subtle rhymes of Williams’ “The Wedding Dance.” While one can find the odd (very odd) rhyme or three in WCW’s poetry, “The Wedding Dance” makes for one of the poet’s more direct concessions to poetry’s most common formal feature. The second stanza gives us “gear” slipping into “their,” picked up again in the fourth stanza’s “headgear,” and more subtly touched on in the final lines of stanzas six and seven, “breeches” and “heels.” Hell, “edges” in the fifth stanza basically rhymes with “breeches.” This thread of slant rhymes approximates the off-kilter, elliptical dance Brueghel depicts. Williams kneads guttural g sounds and harsh rs into his poem, roughening his poetry to match his rustic subject. And yet there’s just the right measure of sensuality that slips through the poem, just enough to get the rough words wet.

Like any successful ekphrasis, Williams’ poem transcends a mere physical description of art. He does describe The Wedding Dance in Open Air, yes, but the description does more than relay the physical contours of Brueghel’s art, or Williams’ analysis of Brueghel’s art—William gives us something of the painting’s spirit, captured in language, sound—another way of feeling something beautiful. Oya!

Hunter in the Snow I, 2016 by Joshua Hagler (b. 1979)