Max Lawton is the translator of many, many works, including a number of books by the Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin. The recent publication of two of those translations, Blue Lard and Red Pyramid was the occasion for my email-based interview with Max. We began in earnest late last fall and finished up on Leap Day, 2024. While Blue Lard was our starting place, we meandered, discussing future translations of Sorokin’s work, like The Norm and Dispatches from the District Committee, as well as some of Max’s other translation projects, books like Michael Lentz’s Schattenfroh and Stefano D’Arrigo’s Horcynus Orca. We also got into Max’s own fiction, which I anticipate seeing in bookstores soon. I want to express my gratitude to Max for generously sharing his time in this interview, and more importantly, making more Good Weird Stuff available to monolingual slobs like me.

Biblioklept: Max! Congrats on the publication of Blue Lard and Red Pyramid. I want to start with Blue Lard, because I think it’s a big deal that it’s getting an English language publication. It’s also my favorite Vladimir Sorokin book that I’ve read, and I know that it’s one of yours as well. The novel is perhaps Sorokin’s most (in)famous one, and I think it’ll attract new readers. What can readers expect when approaching the novel?

Max Lawton: Like TELLURIA, BLUE LARD is all about textures: literary, historical, ideological… However, unlike TELLURIA, BLUE LARD has a telos to it—an endpoint. I am firmly of the belief that BLUE LARD is Vladimir’s best novel. He had taken a long break from prose (about 7 years) before writing it, so this text simply burst forth from him and ended up as a neat showcase of all of his aesthetic preoccupations, but held together by an edifice that has proportions none too short of classically harmonious. What should readers expect… hmm… the first section is rather challenging. One needs to surf its wave and not expect full comprehension. There is a glossary of Chinese words and neologisms at the back of the book, but I’m not sure it’s worth consulting in the expectation of further understanding. The middle section of the book—characterized by a faux-archaic language—is also terribly strange, but with fewer neologisms. The last section of the book—an alternate iteration of Post-WWII Europe—is formally very smooth, but insanely transgressive in terms of content. And I haven’t even mentioned the rather unorthodox parodies of Russian classics in the novel’s first section! What should readers expect? In short: to have their minds blown!

Biblioklept: Yeah, Blue Lard zapped me in the wildest way, and you’re right when you suggest the reader should “surf its wave and not expect full comprehension.” The first section is disorienting, but I think it also orients the reader to the radical disorientation to come. And the parodies of Chekhov, Tolstoy, Akhmatova, et al. are fantastic; there’s something really joyful in these deviant mutant performances. Sorokin constantly shifts linguistic registers in his work, which I know poses challenges and opportunities for you as a translator. For example, you’ve stated that in translating the polyglossia of Telluria you tapped into a range of voices including Chaucer, Faulkner, and Mervyn Peake. I’m curious about your process in translating Sorokin’s Russian classics parodies in Blue Lard.

ML: This is a fantastic question. The fundamental issue, however, is that Vladimir isn’t really interested in parody. If the clone-texts were a neat pastiche of Russian greats, that would be one thing. But Vladimir describes them as “essence hunts.” Oftentimes, they do not read like the authors they are “imitating.” This is especially so for Nabokov and Pasternak. Tolstoy and Akhmatova are in the middle. Then Dostoevsky, Platonov, and Chekhov are right on the money; their essence seems to line up with their outer form––their noumena are no different from their phenomena. For Dostoevsky, Platonov, and Chekhov, I did appeal to previous translations of their work, as not to do so seemed like a grave error. But, for the others, I had to think more outside of the box. With Nabokov, the one thing I “added” to the translation was recommended by a couple of professors and approved by Vladimir: I worked in a few of Nabokov’s pet words in English, as he is actually more famous for his writing in English than in Russian. For this reason, the insanely bizarre Nabokov “essence-hunt” reads more like a parody in English than in Russian––not that it isn’t very alienating in both languages. The Dostoevsky parody was especially fun to translate, as it allowed me to indulge the worst instincts of a Dostoevsky translator. I leave it to you to figure out what that might mean. The fundamental question posed by these parodies and the way they both resemble the texts of the original authors and not is: what does it mean, aesthetically speaking, when phenomena do not align with noumena?

Biblioklept: That seems like a central thread of what I’ve read from Sorokin in general—this aesthetic disarrangement of what we know, or what we think we know, and what might actually, I don’t know, be. To go back to Blue Lard: it reads like the work of someone joyfully detonating and reinventing realities. The “plot” of the novel is a series of displacements that culminate in this fucked up and hilarious reinvention of Postwar Europe. But as you mention above, that section is composed in a really precise, lucid, “smooth” manner, which only serves to highlight its transgressive content. The tonal shift isn’t exactly jarring, because by this point the reader has been through a linguistic gauntlet—but it does imbue the “alternate history” at the end of Blue Lard with an uncanny tinge.

ML: I actually think that the second half of the novel was more difficult to translate than the first. There’s a specific rhythm of Russian speech that is pun-filled and, I guess you’d say, overripe. This is how Russians speak in a sophisticated milieu even now. And I think it comes across as if it were wearing a fedora, so to speak, when it’s translated too directly. For that reason, I went back to the rhythms of dialogue at play in Old Hollywood films to find something that felt stilted but didn’t simply register as dissonance to the Anglophone ear. Of course, translating the narration of the book’s second half was more a question of reduction—making it as transparent as possible so that the horrors at its bottom would be visible. This wasn’t difficult, but was a good exercise in Hemingwayesque (or Sadean) style—Vladimir loves Old Man Ham and doesn’t much like Sade. As somebody who has written a lot of screenplays, Vladimir does sometimes enter a mode of narrative prose that seems to owe a lot to the way that screenplays are composed. With reference to the first half of the book with its constant destabilizing, I would say that it can be easier to translate things that sound utterly deranged because the question of normalcy goes out the window. As you will see in 2025, this is why the Soviet rhythms of THE NORM were a particular pain to render… we simply don’t have that register!

Biblioklept: Okay, so the fact that you drew from Old Hollywood patter actually makes a lot of sense to my ear. There’s like a heightened artificiality to the section, but one grounded in “realism,” which, again, lends to this uncanny rhythm.

ML: Yes, exactly. I have made this comparison before, but it bears repeating: Sorokin is a bit like a Russian hybrid of David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino. I very much hope that the dialogue in my translations of his work falls onto the Tarantino side of that spectrum. It should be crisp patter––highly rhythmic. Not stilted and highly unreal like Lynch’s screenplays. But, as with Tarantino and Old Hollywood films, something in Sorokin’s crispness eventually begins to limp, cloy, gum up the works… to glitch!

Biblioklept: The Norm is Sorokin’s first novel, right?

ML: THE NORM is more or less Sorokin’s first novel. Things are a bit complicated at the beginning because he was simply writing “into his desk” with no prospect of publication. So, the early novels were sort of composed alongside one another. THE NORM is a Soviet Disneyland of abject horror: eight rides, each representing a different aspect of the USSR’s shittiness. Everyone knows it’s the book in which people eat shit, but it actually goes way deeper than that. The section people most love in Russia is a deranged epistolatory one, in which the distant relation managing an intelligentsia family’s dacha loses his mind with rage at having been saddled with its maintenance. Part 5––the best.

Actually, here’s a fun spoiler-free preview of the book––this diagram-thing will be included in the edition coming out from NYRB Classics in 2025.

TRANSLATOR’S LINATI SCHEMA FOR THE NORM

I. Contemporary dialogue. For a Soviet person, the same shock an Irish person might have had upon reading Dubliners. No point foraging through the American ‘80s. Therefore: the NOW.

II. Critical exegesis. These are mere words. American slang when necessary––then to explain the original by way of scholarly apparatus.

III. A thesis: Russian’s rhythms are generally quite defined by rurality. The agrarian empire was industrialized too quickly––couldn’t do away with the rurality of speech. But, so as not to exaggerate, to make the dialogue in “The Scourge” sound like a film noir about louche characters. Again: contemporary speech when necessary (esp. with the editors interrupting the text). Pilfering phrases from Constance Garnett for the Anton frame-narrative.

IV. Making the poems as perfect as any poems can be in translation. Total metrical adequacy.

V. No contractions. A dash of Benjy Compson. Instead of rhyming insults, total obscenity (“dickass professor” instead of the more literal “dickessor”).

VI. The occasional need to make a slogan more grammatical in English than in Russian.

VII. Not perfect lines, but shattered fragments. A meta-commentary on the clunkiness of official poetry (of poetry an sich as well?). The main thing: that the reader feels the clunky, contorted poetry when it supplants the prose, but that I not give into Miltonic excess entirely. Impossible to translate these as perfect poems as in Part V.

VIII. To occasionally add syntax to the gibberish so that it scans. “Jabberwocky.”

Biblioklept: I’m about halfway through The Norm—haven’t gotten to Part 5, which I’ll read tonight. The first section was, uh, hard to swallow, but also very funny. And once it told me how to read it, I was quite taken with how even in some of his earliest stuff, Sorokin has already found this strange, mutating form, a kind of narrative hot potato (or “hot norm” if we’re feeling extra abject today). I loved the third section, especially the sinister shift it takes.

ML: THE NORM is a highly compressed preview of all the tendencies Sorokin would be working out in the first half of his career—all the way up until BLUE LARD. Of course, you have the binary bomb structure of the short stories, in which a highly ordinary situation that would typically make up the raw material of Soviet official prose is ruptured and gives way to something abject. This will be explored a great deal more in the short stories of DISPATCHES FROM THE DISTRICT COMMITTEE, coming out from Dalkey next year. ROMAN and MARINA’S THIRTIETH LOVE, also binary bombs, but novels rather than stories, belong to the NORM-universe as well. Sorokin’s imitation of the world of Russian classics in ROMAN is as precise as his immersion in Soviet shit. Indeed, in THE NORM, one cannot help but note the intense specificity of Sorokin’s engagement with the Soviet Life-World. His prose would not be quite as specific in and after BLUE LARD—it would be more imaginative and less grounded in any one reality. Perhaps what tortured Sorokin during the first half of his career was his inability to imagine a world other than the Soviet Union. In all books after THEIR FOUR HEARTS (so BLUE LARD AND all that follows), though he may be haunted by the Russian past, the worlds he imagines are light and free—defined by his own language alone. After BLUE LARD, it is only his short stories that are weighted down by the gritty details of Russianness.

Biblioklept: You mentioned Russians love the fifth section, the “deranged epistolatory.” I loved the section too—it’s a kind of linguistic unraveling, but a strangely sympathetic one. Why do you think this chapter resonates with Sorokin’s native audience? Can you tell us a bit about translating it—was it fun? Difficult?

ML: That part was only tricky when Soviet-houseware vocab would pop up—obviously not my area of expertise. But, beyond that, in the sections where Sorokin is exploring a very pronounced directionality, I find it somehow easier to ride along with him. Translation is more about translating intent than individual words, so when the intent is very legible, it makes the translator’s job easier. That section is so beloved because it depicts a Soviet archetype of resentment and envy—wasn’t all of that meant to have gone away? Isn’t this the Shining Future? Well, it turns out that people are still animated by precisely the same sorts of petty evil. The idea of this section is a lot like what Dostoevsky wants to convey with the Underground Man: human beings are immutably illogical, petty… From that perspective, there is something divine about the gibberish at the section’s end—as divine as Dostoevsky’s 2+2=5.

Biblioklept: I really enjoy the gibberish and jabberwocky that infiltrates The Norm (particularly the lulling but clunky rhyming in the seventh section). That polyglossic strand seems woven throughout Sorokin’s work but is more palpable in this early novel than his later stuff. (Not sure if novel is the right word for The Norm but I don’t really care.) In Blue Lard and other later works, Sorokin employs neologisms and a range of non-Russian-language terms, but these are deployed in a more narratively-coherent manner than what’s happening in The Norm. In your estimation, is this simply an evolution in style? Is it purposeful, or just a writer doing his thing? Is this a stupid question?

ML: THE NORM is what all of Sorokin’s later works emerge from. In that sense, it’s undoubtedly true that this “narrative experiment” (you’re also right that it’s not a novel in any real sense) is less laser-focused than books like BLUE LARD, in which tropes like gibberish or corporeal-mutilation-as-metaphor have been worked out to a precise science. Sorokin wrote the book when he was a young man, passing around pamphlets of each part to his friends in the Moscow Conceptualist Underground. They were over the moon about it. In fact, there’s no meaningful way in which THE NORM can be differentiated from MY FIRST WORKING SATURDAY (mostly collected in Dalkey Archive’s forthcoming DISPATCHES FROM THE DISTRICT COMMITTEE), ROMAN, or MARINA’S THIRTIETH LOVE. All these books are a singular meta-work that deconstructs the ideological and literary languages of the Soviet Union, during the period when Sorokin was coming of age as an artist.

Biblioklept: Can you tell us a little more about Dispatches from the District Committee? Also, if this is something you can get into, how do you go about placing Sorokin’s work with the U.S. publishers—is there a thought into which titles go to Dalkey and which go to NYRB?

ML: DISPATCHES FROM THE DISTRICT COMMITTEE is the dark Dale Cooper to the RED PYRAMID’s sweet pie-eating FBI man. Whereas the latter was structured in accordance with a certain sort of classical form (yes, it’s fucked, but its stories are fucked (and fuck) in a harmonious way, as it were), DISPATCHES is a collection of early binary bombs from Sorokin’s famous MY FIRST WORKING SATURDAY collection, along with a few bits of juvenilia and a few late-period stories. Without exception, these are woolly and insane tales, some of my favorite things Sorokin has ever written. And it is in this collection that we truly learn the meaning of the “binary bomb” of which he so often speaks: in such stories, the first half is the technically-accomplished outlining of a typical Soviet situation or Soviet literary mode, but, about halfway through the story, the pin of the grenade is pulled and all that which is “normal” about the tale we’ve been reading gives way to the abject and the obscene––to Joycean gibberish and Bataillean acts of violence. In a way, this collection is the ninth part of THE NORM, and I wouldn’t object to readers approaching it in that way.

The publishers themselves divided the books, but I do think there was a certain logic to how it shook out. The Dalkey books tend to be the cult-classic Sorokin novels that are particularly beloved by people in Russia: by his “cult readers.” And the NYRB books are the books foreign readers tend to come to first. This narrative might become a bit stranger in coming years with NIGHTINGALE GROVE and THE SUGAR KREMLIN, but I’d say that’s how the chips have fallen for the time being.

Biblioklept: Speaking of The Sugar Kremlin and different publishers: the manuscript I have includes wonderful color illustrations by Yaroslav Schwarzstein. If I understand correctly, these illustrations have appeared with other editions of the book? Is the plan to include the illustrations in a U.S. edition? The Dalkey edition of Their Four Hearts includes illustrations by Gregory Klassen—has he collaborated with Sorokin on other works? Can you give us some background on Sorokin’s relationship with visual artists?

ML: I’m not sure those illustrations are going to be in THE SUGAR KREMLIN, alas… But Greg Klassen’s wonderful frontispieces for DISPATCHES are going to be included. Sorokin was a visual artist before he was a writer, so his texts are profoundly visual. He also has a lot of love for illustrated editions of his novels and stories––especially the deluxe editions put out by ciconia, ciconia in Berlin. In the future, I would love to put out English editions of Sorokin’s illustrated works that are just as deluxe as the German ones. In a sense, Sorokin writes like a painter. When I read his books, I can always see exactly what’s happening on the page in my mind’s eye. But it’s funny to imagine an illustrated edition of something like BLUE LARD––his linguistic abilities outpace those of any theoretical artist. I am also working to get a couple of American film adaptations of Sorokin’s books and stories off the ground here in LA. Cinema is very dear to him––and he’s written quite a few scripts.

Biblioklept: Yeah, Sorokin’s writing is very imagistic, photographic, cinematic—for all the wild unreal shit that happens, it’s anchored in highly visual, sensual prose. I think that imagistic quality is important to the storytelling, especially when he drops these “binary bombs” as you put it (or is that Sorokin’s term?). I think the term is appropriate; I also like how novelist Will Self describes this signature structure in his introduction to Red Pyramid: “Each of his stories is a sort of mutant Mobius strip, in which to follow the narrative is to experience the real and fantastic as simultaneously opposed and coextensive.” I’m curious how Self’s introduction came about—can you tell us a little bit about that process?

ML: The binary bomb is Sorokin’s term of art for his own early stories, not my own. In fact, the term in Russian is closer to “lil’ binary bomb”. Will’s introduction is just so beautifully written—Vladimir and I think it’s one of the best texts ever written about him. I’d met Will a long time ago—first when he did a reading from Shark at Columbia when I was doing my undergrad there, then when he debated Zizek in London when I was at Oxford (Will won the debate by a wide margin, you can still find it on YouTube). Will has always been one of my heroes—one of the writers whose books showed me a possible path forward with my own writing when I was starting high school. In fact, for contemporary English-language prose, one couldn’t do better than his “technology trilogy”—UMBRELLA, SHARK, and PHONE. Anyways… I’d emailed Will a few times about my writing and received polite replies, but, when I was in London on the eve of the release of THEIR FOUR HEARTS and TELLURIA, he tried to meet up with me, didn’t succeed, then we met up in NYC, where he was doing a bit of research for his new novel. We became fast friends and, just as Will has become a big fan of Sorokin, so too has he become a mentor to me. To my mind, Will represents all that which is glorious about the English literary tradition: its irreverence, wildness, erudition, biting wit… It means a great deal to both me and Vladimir to have him “coming out to meet the reader”—and doing such a damn fine job of introducing the book! To all those readers who haven’t yet touched Sorokin, I would recommend starting out your odyssey with Will’s intro to RED PYRAMID, then reading the collection itself, then reading BLUE LARD.

Biblioklept: You’ve touched on the timeline for publication for some of your Sorokin translations. Any news on when we might expect to see Roman or The Sugar Kremlin on anglophone shelves? What about your translation of Michael Lentz’s surreal opus, Schattenfroh?

ML: The Sorokin timeline is still a bit unclear. ROMAN and THE SUGAR KREMLIN will be coming out in the next two or three years, I would say. Actually, I take that back: THE SUGAR KREMLIN will be coming out in 2025, but ROMAN is a little bit more unclear. There is some discussion of ROMAN and MARINA’S THIRTIETH LOVE being released together in a slipcase.

SCHATTENFROH is the novel. I am most excited about having translated after BLUE LARD. It is such an incredible, strange masterpiece, and I really don’t think the Anglosphere is ready for it. That will be coming out in 2025 and in fact, my translation, or rather, the very final draft of my translation is due at the beginning of the fall, and my editor Matthias and I are thinking a lot about how much work that will be to get done.

Biblioklept: Who’s publishing Schattenfroh? I’m going to ask you an unfair and stupid question: What is Schattenfroh?

ML: I can’t reveal who will be publishing it, but a press release about all these books is coming within the month. In brief, SCHATTENFROH is about a man named Nobody, who, coincidentally, bears a great deal of resemblance to Michael Lentz, being forced to write a book called SCHATTENFROH by his father’s ghost, whose name is also Schattenfroh. The process of the book’s composition—the journeys undertaken during its composition and the technical elements of its assembly (and deconstruction)—are what it’s about. It also deals with family history, metaphysics, World War II, Hegel, the baroque, German urban planning, incest, the apocalypse, death, and much else. It is one of my favorite novels without question.

Biblioklept: Can you touch briefly on some of what went into translating Schattenfroh? The book is formally daunting; at times reading in it is like walking through a surreal nightmare; other times the prose is austere, even spare…

ML: In certain respects, I felt the inherent affinity to SCHATTENFROH I have felt to other texts I am deeply infatuated with as a translator (BLUE LARD, Antonio Moresco’s trilogy, Céline…). On the other hand, the technical vocabulary that crops up from time to time as a conceptual gag was absolutely brutal to work with and I am indebted to my editor Matthias Friedrich for the good work he’s done, of which there is still much to do. The printing press vocab will require a specialist in medieval printing technology to give it a rather intensive read, just as the section in which a museum guard quizzes the protagonist about a technical architecture article from an East German architecture journal will require an intensive edit by a perfectly bilingual scholar conversant in architecture and physics. Lentz has the luxury of using texts as found objects––we, alas, do not! Matthias has also been a great help with identifying quotes, which we then have to translate or find extant translations of. The latter option is preferable, as it safeguards the encyclopedic quality of the book––you see a quote, Google it, and dive deeper into the world of the novel. The most problematic translation question is what to do with historical quotes from Luther and others like him that have been translated into English, but into modern English, whereas the German is dense as hell and difficult to read due to its archaicism. Translations of Luther from the era he lived would be ideal, otherwise I’m left attempting to kitschify the English into an approximation of the archaic German.

Biblioklept: I expect Schattenfroh to become a cult novel for anglophones after your translation comes out. Do you know if it has a similar reputation in Germany?

ML: The fascinating thing about SCHATTENFROH is that it doesn’t have too much of an audience in Germany. It’s very much a cult novel. Its release in English will provide a new opportunity for more German readers to discover it. With that said, those German readers who have read the book have, for the most part, fallen in love with it. It’s the sort of novel one can’t believe is still being written. On the other hand, there’s a way in which SCHATTENFROH is the sort of book that might find an audience in America more readily than it has in Germany—this is just my suspicion.

Biblioklept: And you’re also translating the Antonio Moresco trilogy—is that correct?

ML: Yes, I’m very excited to dredge the depths of its pornographic scatology. It’s one of the most metaphysical projects I’ve ever encountered––moving from Moresco’s own lived experience as a monk and revolutionary to the most distant reaches of interstellar space in a frozen Steinian mode that is as gorgeous as it is infuriating. This trilogy is on the level of SCHATTENFROH and BLUE LARD and will be adored by all readers of 2666, THE 120 DAYS OF SODOM, and SOLENOID. The second book in the trilogy in particular, CANTI DEL CAOS, will be an event in English publishing that I hope will reach the heights of the reception to Bolaño’s masterpiece. I am also translating HORCYNUS ORCA and am still terrified of the Sicilian therein. The great writer and translator Francesco Pacifico will be editing these translations.

Biblioklept: I’ve heard raves of Stefano D’Arrigo’s Horcynus Orca from Andrei at The Untranslated.

ML: It’s thanks to Andrei that I’m going to be translating SCHATTENFROH, Moresco’s trilogy, HORCYNUS ORCA, and, in a few years, Palol’s BOÖTES. He’s a great friend and mentor to me and there are few things in the world I appreciate as much as his taste and total aesthetic honesty. He is a source of great guidance to me, and I am deeply, deeply grateful that I stumbled on his blog and that he responded to me when I sent him the illustrated manuscript of THEIR FOUR HEARTS back in 2019. A true OG.

Biblioklept: Amazing. Andrei is a champion reader. Reading is such a private, internal process; it’s easy to overlook that great writers need great readers. And translators are clearly in the vanguard of great readers.

This is probably a really stupid question, but when you’re writing your own fiction, like your novel The Abode, are you in, like, a totally different zone than the translation sphere?

ML: Will Self always asks me about this and expresses concern that I’m being over-influenced by the fiction I translate, but, for whatever reason, I have found that translation is a self-contained system in my literary life. The words of the original enter me, then are flushed out like water turning into piss. I have the capacity to be influenced by texts, but the very fact of translating means that I also exorcise the influence. The commonality between my own prose and translation is the focus on style, but the difference is the question of what to write that must necessarily plague any original writer. That is the most difficult part of writing––ontological doubts. I have a good feeling that the Anglosphere will soon get to read my first novel PROGRESS, my short-story collection THE WORLD, and my second novel THE ABODE. These three books represent the first era of my writing. After I’m done with THE ABODE, the autofictional monstrosity I’m writing now, I’m going to stop writing for a while––just play black metal with my new band here in LA and read. Then see when I’m driven back to the blank page (though, to be honest, I’m half-lying: I already have two new novels planned out––they’re just very different from the first three books).

Biblioklept: To your parenthetical post-dash clause: When you write that your plans for these two new books differ from the first three, what do you mean? Style? Subject? Did this difference come from a conscious choice?

ML: Yeah, the first three are very selfish books in a sense. MAX LAWTON looms over them rather heavily. For the follow-ups, I’ve been thinking about certain American styles that are generous, biblical: Cormac McCarthy, Marilynne Robinson, etc. I want to write a few books from which I am utterly absent, and I want them to be shorter, with the sentences screwed in tight. In brief, I want to write grown-up books. These first three are my graphomaniacal youth-culture books––Bret Easton Ellis casts a long shadow over them too.

Here are links to a few of my short stories that have recently been published:

(And again, Svetlana Sachkova’s Russian translation.)

And Matthias Friedrich’s German translation of “The Man Who Signed Too Much”

Biblioklept: There’s that line near the end of the prologue of The Abode, where the third-person narrator tells us that “Max wasn’t interested in the ups and downs of a typical Bildungsroman or campus novel”…

ML: Yeah, I’ve always wanted to write a massive slab of autofiction but am keenly aware of the clichés that dog the form. This is the sort of cheeky line that might get thrown out in further revisions of the text but represents my desire to combine disparate tendencies: the neuroticism of Proust, the hedonism of Bret Easton Ellis, and the metaphysics of William Blake. Though my German reader says it reminds him of THE CORRECTIONS… In a sense, THE ABODE is all about wanting my cake and eating it too.

Biblioklept: I liked the line, especially in its context, which I hope you don’t mind if I share here with some readers:

“Max wasn’t interested in the ups and downs of a typical Bildungsroman or campus novel, didn’t believe he’d ever end up with a single woman to whom he would pledge his affections––he was the plinks of the second synth coming in over the washes of the first and each click of the metronome showed him something else––something he was meant to see, something pure and visionary that had been vomited up from the very center of the earth.”

The synth metaphor is lovely.

ML: Thanks so much! I tried to make the language chewy and specific without losing the pellucid quality of 19th-century narrative prose. My first novel PROGRESS is very dense stylistically in a way I strived to move away from.

Biblioklept: The style of Progress seems to rhetorically approximate the narrator’s attempt to register the material world he is moving through with his sense of interiority, selfhood, whatever. (That inside/outside distinction manifests in a number of the book’s motifs, including all the pissing and shitting.) I don’t know if I think of the style as dense, necessarily. The clauses stack up, but they also flow and move. I mean, I think the book is quite readable; it’s not like, Oh fuck another giant paragraph! Maybe that’s because Progress is, at least in part, about, “Y’know, like, apocalyptic stuff,” to quote one character out of context.

ML: I wrote PROGRESS during Covid and the lack that seemed to inform it was my feeling that narrative prose had ceased to describe the world as it exists (I was also reading a lot of Heidegger at the time). The conceptual sci-fi narrative is an excuse to describe the freeways and all that exists around them as if it were a natural idyll. The book is a beach on which the detritus of our age washes up––I catalog it.

Biblioklept: So, besides your novel Progress, your short story collection The World, your autofiction-in-progress The Abode, the Moresco trilogy, Horcynus Orca, Schattenfroh, and a slew of Sorokin–what other projects are you cooking up?

ML: There are a couple of others (as if I didn’t have enough on my plate!). First is my new translation of GUIGNOL’S BAND in a single volume––the previous translations of the book’s two parts were done by two translators and put out by two publishers. It is my contention that GUIGNOL’S BAND may be Céline’s greatest novel. The extremity of his style increased all throughout his career, but, by the time it reached its point of extremity, the content had, alas, curdled (here, I’m thinking of the final trilogy recounting his years spent as a Nazi). GUIGNOL’S BAND, on the other hand, is a showcase of the way Céline would blow up his own idiom, but in the context of a propulsive London novel with a lot of crime and capers. It is my hope that a new translation of GUIGNOL’S BAND will truly bring home to the Anglosphere the quiddity of Céline’s “musical orality.”

My friend Ralph Hubbell and I are also hoping to translate Oğuz Atay’s great novel THE DISCONNECTED, which has already been translated into English, but, speaking delicately, needs to be redone if it is to be published (Ralph and I have written a lot about this and gotten into hot water for what we’ve said). The book is akin to a mix of ULYSSES and CATCHER IN THE RYE. It’s the best novel ever written in Turkish, and I sincerely hope we get good news from Istanbul in the near future––the offer from the Anglophone publisher that wants the two of us to retranslate the book still stands.

Biblioklept: The last time I interviewed you, I ended with my standard last question, Have you ever stolen a book? and you admitted that you hadn’t. Any updates there?

ML: I still haven’t stolen any physical books, but I hope that my work continues to be another kind of theft: stealing great books out of the maw of Anglophone oblivion and putting them into the hands of readers eager for fiction that is dense, extreme, and difficult. I am of the sincere conviction that the demand for these books is high and, to any Anglophone publishers reading this, I say this: take a chance, publish something that pushes the envelope, and you might just be surprised by the reaction…

In my original review of

In my original review of

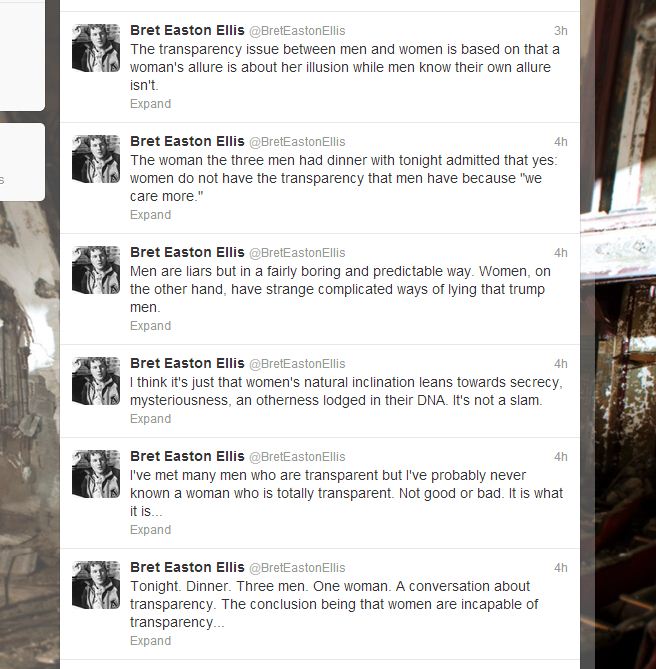

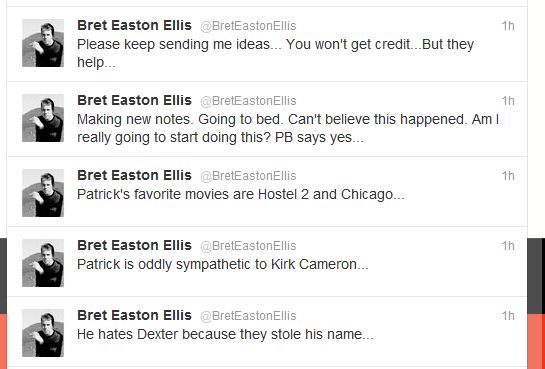

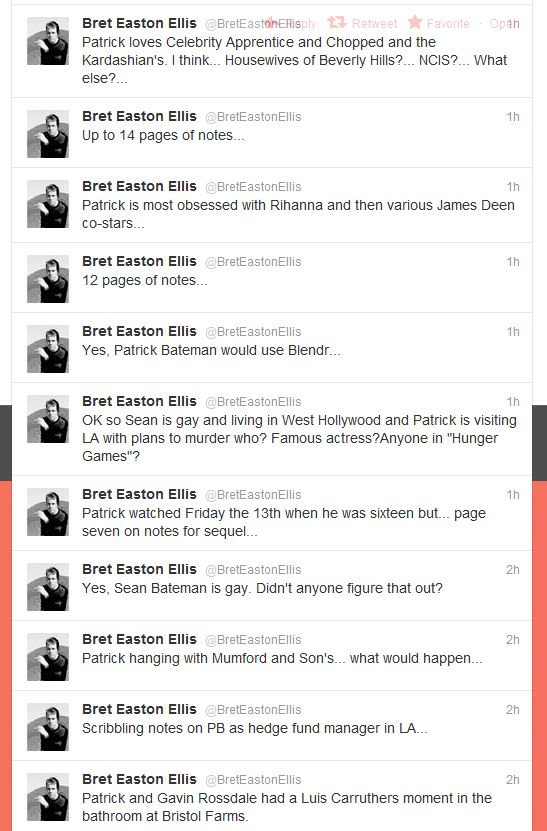

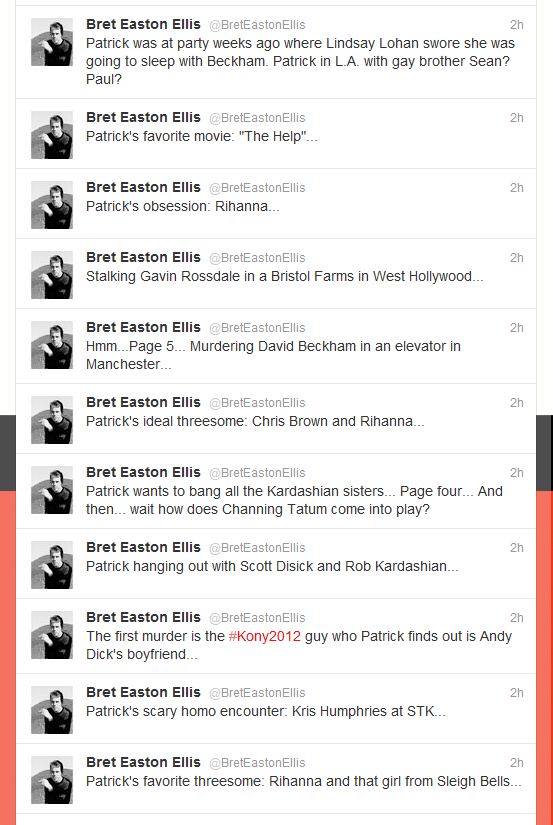

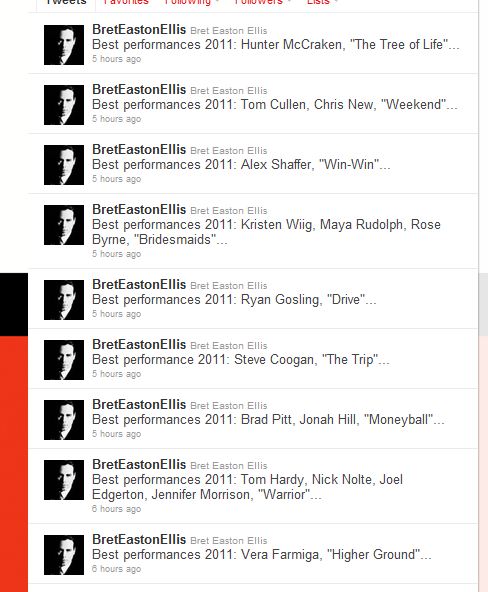

I’m not sure what Ellis’s tweet meant, and attendees of the Hackney reading claim that he was more considered and measured in his tone than the actual words of his response seem to entail. His end of the agon with Wallace is also rife with its own set of problems—his contemporary is dead, horribly dead, a suicide, (the kind of death that makes an essay like this one, an essay that claims to find affirmation of life in DFW and empty nihilism BEE, particularly hard to swallow, I suppose)—making it all the harder to respond. I read his “too soon” remark from the Hackney reading to be in earnest.

I’m not sure what Ellis’s tweet meant, and attendees of the Hackney reading claim that he was more considered and measured in his tone than the actual words of his response seem to entail. His end of the agon with Wallace is also rife with its own set of problems—his contemporary is dead, horribly dead, a suicide, (the kind of death that makes an essay like this one, an essay that claims to find affirmation of life in DFW and empty nihilism BEE, particularly hard to swallow, I suppose)—making it all the harder to respond. I read his “too soon” remark from the Hackney reading to be in earnest.