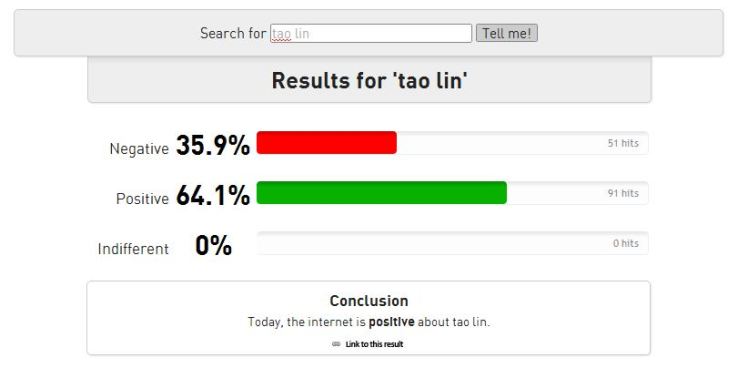

I am taking a class titled 21st-Century Fiction: What Is The Contemporary? and three of the books in this photograph are part of the reading list. Absent titles are by Dan Chaon, Kathryn Davis, Ben Marcus, Blake Butler, Sheila Heti. Some others. Wanted titles: Tao Lin’s Taipei (which I am reading now, which is surprisingly good).

I don’t know anything about Dodie Bellamy beyond the fact that she is often grouped with Kathy Acker, who are both often grouped with Dennis Cooper, who are all New Narrative people. New Narrators make the author present, her body and sexuality usually the prime subject. Letters of Mina Harker is a “sequel” to Dracula, except Mina Harker is a young woman who lives in 1980s San Francisco. On conceit alone, it reminds me of Kathy Acker’s Don Quixote: Which Was a Dream.

Richard Powers and Evan Dara are often grouped together, mainly because Powers blurbed his first book, The Lost Scrapbook, and that both of them write books that weave disparate discourses into their fiction. Also, there is speculation that Powers is Dara (Or Dara is Powers). Flee is, according to its publisher Aurora Books, about “in which a New England town does just that.” I’ve read the first chapter, titled “38,839,” and it reeks of Gaddis (in a good way). Disembodied voices colliding into each other, a cacophonous plot; the absurd & banal drama of everyday, throwaway conversation. An Australian book show on Triple R Radio, who have a good and very rare interview with Gerald Murnane (whose book Inland I was really, really jazzed on), also really loves Dara. I’m pretty excited to read this one.

Evan Dara and Richard Powers are often grouped together, mainly because Dara’s first book was blurbed by Richard Powers, and that both of them write books that weave disparate discourses into their fiction. Dara might be Powers (or Powers might be Dara?), but that doesn’t really matter. The Echo Maker is supposed to be one of those Big, Important American Books (as noted by the shallow, embossed seal on my used copy of the book). As I write this, I am listening to Powers read from The Echo Maker from an old Lannan Foundation talk (who also really love Gass) and I am really intrigued. I haven’t flipped through this, so I will reproduce the back copy.

On a winter night on a remote Nebraska road, twenty-seven-year-old Mark Schluter has a near-fatal car accident. His older sister, Karin, returns reluctantly to their hometown to nurse Mark back from a traumatic head injury. But when Mark emerges fro a coma, he believes that this woman–who looks, acts, and sounds just like his sister–is really an imposter. When Karin contacts the famous cognitive neurologist Gerald Weber for help, he diagnoses Mark as having Capgras syndrome. The mysterious nature of the disease, combined with the strange circumstances surrounding Mark’s accident, threaten to change all of their lives beyond recognition.

Can Xue (which roughly translates from Chinese, according to my mother, to “persistent & dirty snow”) is hailed by western critics to be the Chinese avant-garde heir to Kafka and Borges. Can Xue is a pen name for Deng Xiaohua. She is of my mother’s generation and her class, which means she grew up persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, which means she was sent to a “re-education camp” in the Chinese sticks and learned to farm. She taught herself English, has written criticism on Kafka and Borges. The strangeness of Kafka echoes in Xue. While the former’s strangeness arrives in the narrative with a kind of grim inevitability, the discovery of a debilitating truth lands like an obvious punchline that the reader stupidly forgets (or realizes too late, like the classic Seinfeld episode “The Comeback“), Xue’s arrives with a kind of startling innocence against the backdrop of dramatic irony. It is like watching, in Michael Haneke’s words in his great interview in The Paris Review, a tragedy from the perspective of an idiot. The title story, “Vertical Motion,” can be read here.