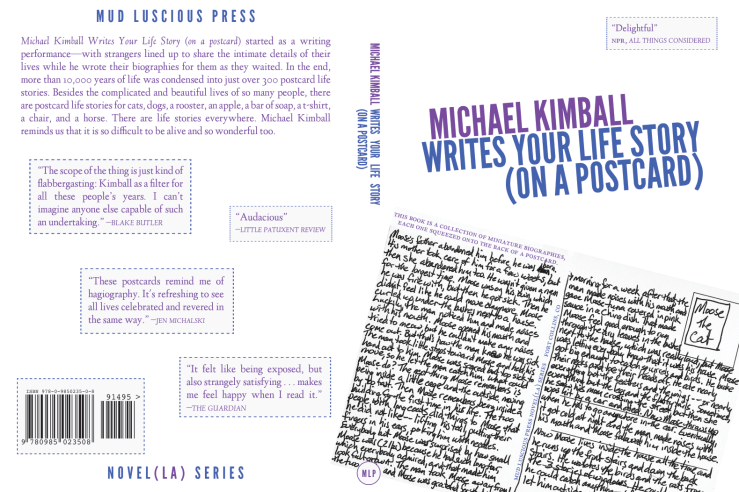

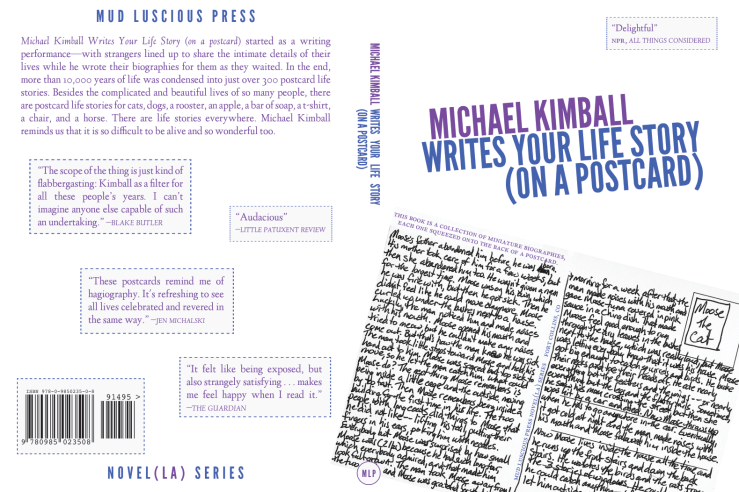

Michael Kimball’s latest book Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (On a Postcard) had its genesis in a performance piece at the Transmodern Performance Festival a few years back: Michael interviewed people for a few minutes and then crammed their biographies onto postcards. The project soon evolved into a blog, where Michael interviewed hundreds of people of all ages from around the world. The work is now collected in a book from Mud Luscious Press that features over fifty of the biographies, including the life stories of several contemporary writers, one dead U.S. President, a rooster, a T-shirt, a few cats, Edgar Allan Poe, and Michael himself.

In addition to Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (On a Postcard), Michael is the author of Big Ray, Us, Dear Everybody, and The Way the Family Got Away. He still holds the Meryl S. Colt Elementary School record for the 600-yard dash. Check out his website.

Michael was kind enough to talk to me about this latest book over a series of emails.

Biblioklept: What’s the hardest thing about writing someone’s life story on a postcard?

Michael Kimball: There are difficult things at different stages of the process. The first difficult thing is asking the right questions for the particular participant. The second difficult thing is being representative when condensing what I’ve been told. The third difficult thing is writing small enough to squeeze six hundred words or so onto a single postcard.

Biblioklept: When you started the project, it was a planned performance piece of sorts, but your description of it at the beginning of the book makes it seem rather off-the-cuff. Did you have a plan for the questions you would ask? How did the questions change as the project progressed?

MK: That first performance was definitely off-the-cuff. I had no idea what I was going to ask people and how I was going to write their life stories on a postcard. I mostly started with something pretty open-ended and then asked more specific questions about whatever I was told. As the project progressed, I developed a set of starter questions that elicited basic information and then asked more specific questions from there. Basically, I considered whatever I was being told to be important and then asked more questions about it.

Biblioklept: You interviewed people by email, in phone, in person — how did how you were doing the interview affect the process? Did you prefer one way over the other?

MK: I preferred the in-person interviews. There was a different kind of intimacy with those and there are a bunch of people I interviewed that way who are now friends. Of course, that wasn’t practical for lots of the interviews, since most people lived so far away from me. And the method did influence the process. With the phone interview and in-person interviews I was taking notes as fast as I could, but that was never fast enough. With the email interviews, it was easier for people to give me more detailed answers. Also, since I had the full text of their answers, I could use more of their language.

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

MK: I tried to use the participant’s language wherever I thought it gave some sense of the person. At times, I thought of like using third-person close narration. Besides that, I was trying to be as objective as possible and I think that gave the life stories a certain consistency of tone. Clearly, I tend to write sentences a certain way, but beyond that I tried to keep myself out of it.

Biblioklept: What about pieces like “Chair” or “T-Shirt” — how did they come about?

MK: The first non-person one I wrote was Red Delicious Apple, which popped into my head almost fully formed, which happened because I used to almost always have apples on my desk, which just meant that I spent a lot of time with apples. But writing Red Delicious Apple opened up a lot of possibilities and so T-Shirt is written about my favorite t-shirt and Chair was written about a chair I once broke. And I have a great affection for animals, so I loved writing ones like Moose the Cat, Sammy the Dog, and Abby the Horse.

Biblioklept: You wrote over three hundred postcards. How did you choose which ones you would include in the book?

MK: The book would have been over seven hundred pages long if I had included all the postcard life stories, but it was difficult leaving any of them out. So, ultimately, it came down to trying to showing the range of the postcard life stories, which is why nearly every one I wrote about a non-human made it into the book.

Biblioklept: How did the Poe biography come about?

MK: That was for Gigantic’s Gigantic America issue. They asked me to write one of the great American bios that they printed on special card inserts and I suggested Poe, who had just had some anniversary of his life or his death.

Biblioklept: Several pieces in Life Story are about contemporary writers. Was writing about these writers different than writing about anyone else in the collection?

MK: Early on, it was other writers who seemed particularly keen on the project — Adam Robinson, Karen Lillis, Elizabeth Ellen, Elizabeth Crane, Blake Butler, etc. I approached every postcard life story the same way, but then let the participant tell me where they wanted to take it. I tried to ask questions that followed their answers.

Biblioklept: I imagine most people who asked to participate in the project were forthcoming with their answers. I’m curious though if you noticed any topics that people avoided or glossed over or maybe required additional prodding from you. Did you ever feel like your part of the interviewing process pushed your subject into uncomfortable territory?

MK: I didn’t realize it until later, but part of what made the project work was that people came to me wanting to tell their life story (rather than me asking them if they wanted it told). Still, there were a few times that people were reluctant to say things. There was one woman who was reluctant to talk about her husband and I couldn’t figure out why, but then they divorced not long after that. And there was one man who didn’t want to talk about his mother because she was really sick. But usually if there was reluctance, it was some kind of abuse or some other horrible thing that had happened to the person. In fact, I was reluctant to talk about the abuse I grew up with in my own postcard life story when it was initially written. In general, I tried to ask the difficult question, but then let the participant decide whether they wanted to answer and how much they wanted to tell me. And with particularly difficult life stories, I always showed the participant what I wrote and asked them if they were OK with it being public before I ever put their postcard life story out into the world.

Biblioklept: Talking about one’s own life clearly has some kind of therapeutic value. Do you think reading about one’s own life carries a similar value?

MK: Since starting the project, I’ve learned there are quite a few therapeutic techniques that involve narrative and telling (or retelling) one’s life story. Part of that process is hearing one’s life story told back or reading about one’s own life. There can be something useful in that perspective and there can be something reassuring about having a manageable version of one’s life story.

Biblioklept: What are you working on now?

MK: I’m very slowly working on two different novels and thinking about a third. I’m not sure if I’ll ever finish any of them.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

MK: I used to steal so many books, especially when I didn’t have the money to keep pace with my reading appetite and I couldn’t find the things I wanted to read in the library. I’ve tried to make up for that by giving away lots of books these days. I stole so many books that I’m not sure I can remember a specific instance. But it was always kind of thrilling and it seemed to make reading all the more exciting. Sometimes, if I didn’t like a book I would sneak it back into the bookstore.

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…

Biblioklept: Did you prefer to use as much of the subject’s language as possible? Maybe I’m getting into what you described as “the second difficult thing” — how much of yourself do you see in the pieces? I think there’s clearly a voice, a tone that unifies the pieces . . . I’m curious how much of the process was crafting or editing or revising or repurposing the subject’s original language…