In high school I bought American Psycho from Barnes & Noble and read it in a few weeks. I knew it was full of awful, horrible stuff that I would never be able to forget but I did it anyways. I was fascinated, revolted; I laughed out loud. I became that one guy that burst everyone’s bubble by telling them that the movie sucked or at least totally missed the point of the book (whatever point there might have been) and that it also left out every one of the funniest scenes, and, oh that the ending was total bullshit. People would ask me if I “liked” the book and I would evasively respond: “I don’t know if it’s a book one can actually like…” or “I don’t know if like is the right word…”—and just generally avoid making any kind of decision about the book, or its author, that prince of darkness Bret Easton Ellis.

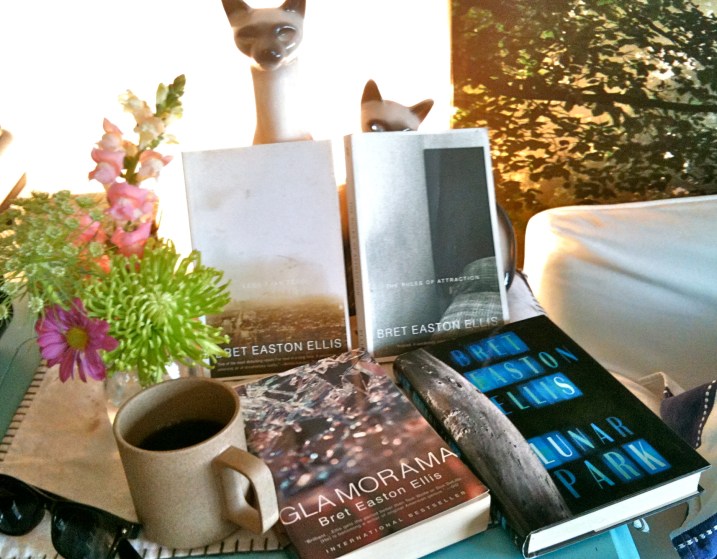

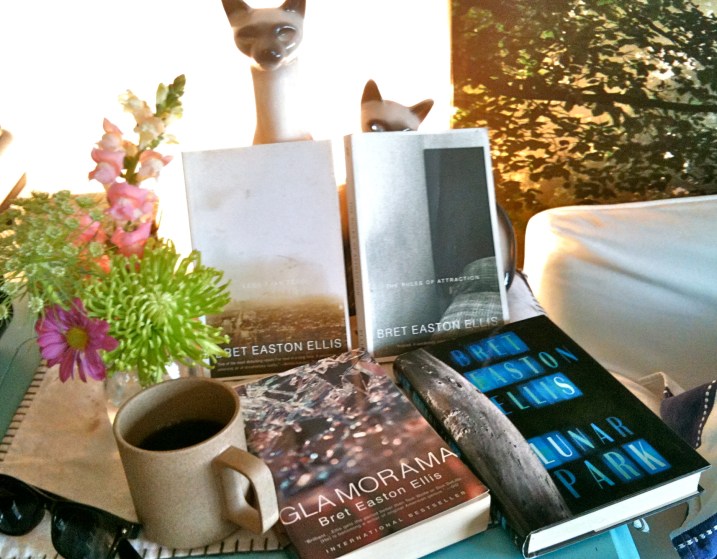

But Bret Easton Ellis intrigued me. Later, when the film Rules of Attraction came out I saw it in the theater by myself and purchased the DVD. It was a much better film than AP, and that was satisfying to me in some way. I didn’t read the book, nor was I moved to seek out Less Than Zero, although at some point I found Glamorama at a used store and bought it for the heck of it, but I don’t think I ever even tried to read it. I was interested in BEE but only from afar. He had definitely scarred me with AP. It was a singular experience at the time and (to this day has maybe been matched only by Jerzy Kosinski with my combined readings of Steps and The Painted Bird). I wasn’t really looking to be haunted in that way any time soon.

I can still remember where I was when I heard about Lunar Park. I read about it at The New York Times, on the family computer at a friend’s parents’ house in Rutland Vermont. I saw that Ellis had a new book, skimmed the article, and saw mention of “meta” elements, the use of a character named “Bret Ellis” who was decidedly not intended to be the actual author of the book, but rather a sort of parallel dimension version of BEE who had settled down in the suburbs and had kids. This was all interesting to me and I made the mental note, “Read Lunar Park.” That was in August 2005.

Fast forward to May 2010. In the five years since Lunar Park came out everything about my life has changed. I am living in Los Angeles pursuing a career in screenwriting. I have been married for a year and I have an apartment and two cats. And it is in this apartment that I come across a VICE interview with the man himself, on the eve of the publication of his new novel Imperial Bedrooms. I find myself reading the interview and it dawns on me that I have never read or heard this man speak, I’ve barely seen photographs of him, and that basically everything I think I know about him has been pure conjecture derived from conversations over the years.

My idea of Bret Ellis as this detached, cynical, deviant creature is immediately thrown out the window by seeing pictures of him wearing a hooded sweatshirt and sitting at a desk. In some of the photos green palm trees can be seen behind him and it becomes clear very quickly in the interview that he now lives in Los Angeles as well. I end up reading the entire article and thinking that Ellis is just a guy like anyone else, not especially pretentious or malevolent, as he had been accused of being by people I had spoken with at times. And what’s more he made reference to “the Stephen King part” of Lunar Park.

My mind exploded.

What Stephen King part? I remembered and reinstated my mental note: “Read Lunar Park.”

And a few weeks later, as though on cue a beautiful hardback first edition copy of LP appeared at the used book stand at my neighborhood farmer’s market. I bought it on a Saturday morning and opened as I was cooking lunch, expecting to get a taste and maybe read a page or two while the food cooked. I ended up sitting on the couch for the entire day reading. That night I couldn’t wait for my wife to fall asleep so I could sit up late and maybe finish, and I started to do just that until I became so frightened by the story that I literally had to put it away until it was light outside. I had a little trouble sleeping that night but ultimately it was okay, and the next day I finished the book. Immediately I was on the phone telling friends to read it. I made several of my local friends borrow my copy and one-by-one everyone came back to me with the same positive report, and regardless of their previous experience or lack-there-of with Ellis’s writing, everyone who read it adored it.

My admiration extended past just the book or my experience reading it. It reconciled the past and my memories and suddenly I found myself saying “I like Bret Easton Ellis” or even going so far as to thinking of myself as a fan of his. I slowly started keeping up with his online presence, (going so far as even joining Twitter just to follow him) and I find the experience genuinely rewarding. Don’t get me wrong: he’s obviously a weird guy sometimes (anyone who could write the habitrail scene in AP would have to be I guess) and I don’t always agree with his randomly asserted opinions about books and movies (I disagree in particular with him about music: our tastes are just simply different). But overall, I think he has a valid and useful perspective on culture and entertainment. Perhaps some of the detractors still see him as the austere, decadent, nihilistic provocateur that I feared and resented in high school, but I have an impossible time jiving that notion with the man who tweeted recently that he had been talked into getting really stoned and going to see The Lorax.

And I guess this all ties in with his recent series of tweets that he is considering a pseudosequel to American Psycho. Suddenly, this proposition seemed so appealing. It’s been twelve years since I read AP, and in that time I don’t think I’ve ever opened it again, and now suddenly I find myself wanting more, hoping that Ellis decides to go through with it.

So yesterday in excited anticipation I went down to the farmer’s market and this time the used book guy had two beautiful paperback copies of Rules of Attraction and Less Than Zero. I bought them both. Even if Ellis does convince himself to write the Los Angeles Patrick Bateman story, it will be years before it will be published and in my hands, so I guess I need to relax and catch up on everything I missed out on so far.