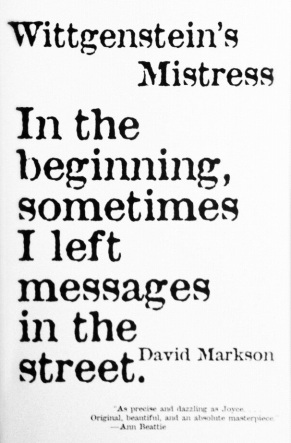

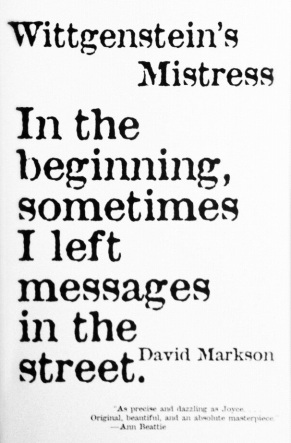

This is not a review.

This book was recommended to me.

An experimental, philosophical novel.

I really wanted to like this book.

I had read the reviews & after being unable for a few years to buy it secondhand, I bit the bullet & bought it new.

The beginning is intriguing.

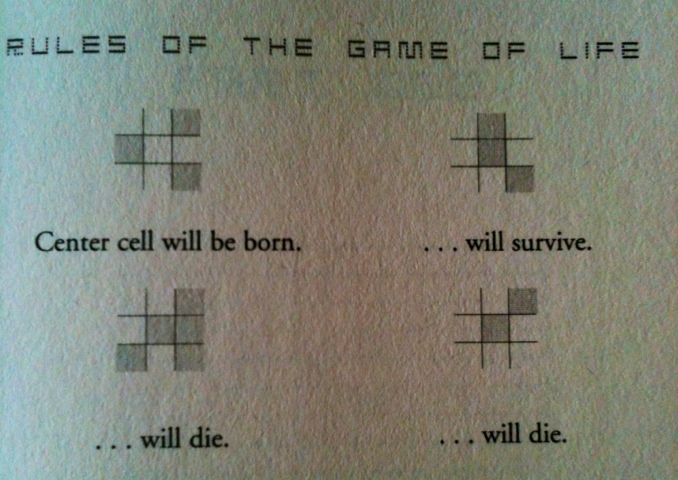

The concept of the book is dead simple.

The idea is this: Kate is a painter; she is the last person on earth, maybe; she is alone in a house on the Long Island beach

Markson picks up Kate’s dialogue in media res and trusts the reader enough to piece together what the heck is going on: she is the last person left on earth and is making her way through it as best she can, telling us her story as she goes.

Short declarative sentences loop feverishly around her brain, repeating themselves, correcting themselves, contradicting themselves, and filling in missing information many pages later.

The narrator’s voice rings true.

It is frustrating, repetitive, and does not offer much in the way of style and language.

No chapter breaks, no real paragraphs even.

Read at random.

This book received 54 rejections before finding a publisher. This I can believe.

Her little apercus are all about observation and remembrance, the real and the false, blah, blah.

(Joyce, Baldwin, Pynchon, Cortazar).

The book was meandering, rambling & jumped all over the place.

Not that oddness is bad.

It never centers on anything.

It’s the type of book best discussed in groups, since it does bring up some interesting themes—the fragility of memory and sanity, the ineffectiveness of language, the impact of philosophy and literature.

There’s nothing for the reader to latch onto and follow, other than the voice.

What about the subtext?

Like Wittgenstein said, “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent.”

I am mad. I am crazy. Yesterday I died but returned in time to write this.