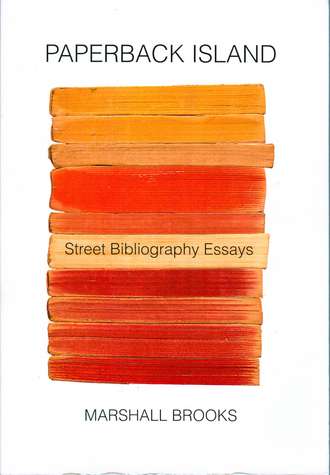

Marshall Brooks’s recent collection of memoir-essays Paperback Island explores the ways that friendship and place influence what we read, how we read, and how we make—and keep—books. Marshall began his career in publishing in 1971, reading manuscripts for Harry Smith at his legendary publishing house The Smith. In 1979 he created Arts End Press. Subtitled Street Bibliography Essays, Marshall’s latest book provides fascinating insights into a world of post-Beat publishing that is slowly slipping away (that is, aside from in memories and books). Marshall was kind enough to talk to me over a series of emails. He was generous and thoughtful, and also interested in my own life—in my kids, in my reading and teaching, but also in the bookstores in my community. It was a pleasure to talk with him. The end of our email exchange found him in NYC, attending a memorial for Harry Smith. Marshall lives in Vermont with his wife and two sons. Check out his website and read my review of Paperback Island.

Marshall Brooks’s recent collection of memoir-essays Paperback Island explores the ways that friendship and place influence what we read, how we read, and how we make—and keep—books. Marshall began his career in publishing in 1971, reading manuscripts for Harry Smith at his legendary publishing house The Smith. In 1979 he created Arts End Press. Subtitled Street Bibliography Essays, Marshall’s latest book provides fascinating insights into a world of post-Beat publishing that is slowly slipping away (that is, aside from in memories and books). Marshall was kind enough to talk to me over a series of emails. He was generous and thoughtful, and also interested in my own life—in my kids, in my reading and teaching, but also in the bookstores in my community. It was a pleasure to talk with him. The end of our email exchange found him in NYC, attending a memorial for Harry Smith. Marshall lives in Vermont with his wife and two sons. Check out his website and read my review of Paperback Island.

Biblioklept: Will you tell us a little bit about how Paperback Island came together?

MB: My original idea was to write about the books that a friend and I shared in our youth and on into our early twenties. My friend was a champion reader. I had recently published a piece about this reading friendship. A strictly “about books” piece related to the story sounded like a good idea, but I quickly became bored with just writing about the books alone. In the end, it was not a challenging enough assignment. A recently completed piece about attending Tuli Kupferberg’s funeral and another piece celebrating sub-underground journalist Sid Bernard more ably filled the bill in terms of complementing the first story. From there, the book took on a life of its own. By the end, I was hard put to keep up with its various twists and turns. It was unlike any other writing experience that I have ever had. Owing to my wife’s keen editorial encouragement, I persisted — for the better part of a year. It is really a book about people whose lives are, or were, inextricably intertwined with books. I love books, but I love people more. My journalist friend Bill Ruehlmann pointed this out in his review of the book. He’s right. Ultimately, PAPERBACK ISLAND is all about love.

Biblioklept: The opener about that “champion reader,” Liam O’Dell, resonated strongly with me, as I imagine it will with other people who love books and reading—most of us have had someone in our lives who pushes us to read new stuff, different stuff.

In the same essay, you talk about how the early 1970s was a kind of information age that prefigured the internet. At the time were you aware of a shift in access to information, books, etc., or was this change something you only noticed after reflection?

MB: I was very conscious of the shift at the time. It was intoxicating.

Biblioklept: What was that shift like, as a reader? What sources were most important to you?

MB: Beginning in public school — ca. 1966 – 1971 — new paperbacks were for sale in the schools, courtesy of a special program to encourage independent reading. A lot of Signet books to begin with, and, later in high school, Vintage Books, among others. These books had all been designed (or, in many cases, redesigned) with an entirely new, young hip readership in mind. (E.g., 1984 and ANIMAL FARM.) They were not the drear-looking relics of my parents’ generation. The new, fresh book design suggested possibility to me. Genuine potential, plus limitless variety. Memorable reads: THE MYTH OF SISYPHUS (with cover art by Leo Lionni — Leo’s son, Mannie is a fan of PAPERBACK ISLAND, by the way); Dos Passos’s USA trilogy (with pen & ink illus. by Reginald Marsh); A CONTROVERSY OF POETS contemporary poetry anthology (Anchor Books, 1965, ed. by Paris Leary and Robert Kelly); EXPRESSWAYS, poems by J.D. Reed (Simon & Schuster, 1969, pb ed.); STUDS LONIGAN, by James T. Farrell (Signet). The underground / alternative press was also an important influence (these papers being highly visible in Boston — they were hawked on the sidewalk all over town). The underground press scene dramatically symbolized that just anything could be written about and printed. Indeed, thought. The papers’ contents often made little or no positive impression on me, but the overall freewheelingness of the papers certainly did. Society, obviously, was becoming much more fluid, looser — Richard Nixon or no. Impossible for a teenager to miss. There were also two reliably good sources for small press publications in Cambridge: the Grolier and Pangloss bookshops. The former only sold — sells — poetry. Most of the time, I did not know what to make of the little magazines that I bought. But this was a good thing — something I looked forward to — being another instance of where you had to make up your own mind about something owing to its relative strangeness, its resistance to categorization. I put a great deal by being able to do this.

Biblioklept: You bring up James T. Farrell here—there’s a fascinating chapter of Paperback Island about how you came to possess a large number of his paperback books. It’s one of several microlibraries discussed in the book. Why are microlibraries important in the age of digital archives?

MB: As you know, children’s books — in traditional book form — remain popular with both children and their parents. In the same vein, I believe that micro libraries fulfill a similar need. The physical surprise quality of the book is married with other special elements and the experience of the book (or books) becomes very much more than simply its contents. In the case of the JTF Paperback Library, Farrell himself is physically detectable. For all that I know, his DNA may well be present (he left enough fingerprints). For some people, myself included, having an author’s library — either whole or in part — can be a stirring experience. Humbling, too. Digital archives have their place, but I don’t think you can savor them in quite the same way that you can a cache of books — a collection you feel privileged to either own or borrow from. I think we all need a form of savor. Bibliophiles, notoriously, know where to find theirs.

Biblioklept: Do you feel antipathy toward e-readers like the Kindle or Nook?

MB: Not at all. My wife just returned from a writer’s conference in Boston (theme: using social media). The breaking word in Boston was that all sales are up — e-books, traditional books, and so on. If there are more readers everywhere, great. I also think that many books should only be available electronically or are best served this way.

Biblioklept: What kind of books are best served electronically?

MB: To return briefly to the idea of the 1970s prefiguring the internet and related developments, I remember well the 1971 publication of the COMPACT EDITION OF THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY being hailed as revolutionary at the outset. William Buckley reviewed the, then, space-age OED in the NY TIMES and shared with everyone how he was customizing his copy with Scotch-taped tabs so as to facilitate his word searches. 12 volumes, 150 pounds worth of books, shot down to two crisply printed volumes (slipcased, replete with a high-end Bausch & Lomb magnifying glass in its own drawer). All this via the miracle of offset printing technology. 21 years later, the cd-rom version of the OED arrived. I still have my copy of the two volume OED, by the way, purchased for a dollar from the Book of the Month Club 30 years ago. But I honestly don’t know if the BOMC, itself, still exists. Well, easily enough clarified — I’ll Google it. [Ans.: It exists. M.B.]

It is difficult to imagine the OED not being served well by the latest technology in light of e-media’s enhanced cross-referencing and search powers, for example, or the ability to present a practically limitless amount of information, which, previously, had to be squelched. All sorts of books, could benefit, really, via the e-book format including guilty pleasure reads. Why sacrifice — or recycle, even — wood pulp on their account? But in the instance of Sid Bernard’s THIS WAY TO THE APOCALYPSE, designed by Stephen Dwoskin — who so deftly exploited both “hot” and “cold” type in his design work, and was, later, a noted underground filmmaker as well — I’ll opt for the original letterpress edition over any other. Likewise, the companionably funky, pocket-size 3rd edition of the AMC NEW ENGLAND CANOEING GUIDE (1971), with its map pockets fore and aft within the inside covers. (THE AMC GUIDE — Liam O’Dell’s bible, by the way.) The new stuff can be great — and lead to wonderful things — but let us not disparage good, traditional book design either.

Biblioklept: How did you meet Harry Smith? What were some of your early experiences at The Smith?

MB: I met Harry Smith in June 1971. After having written him earlier in the year inquiring after work — of any kind — Harry offered me a part-time editorial job doing a little of this and that. It was a decidedly free-form proposition. I went to The Smith in lieu of attending my high school graduation in Massachusetts. Located at 5 Beekman Street, in Downtown, NYC, The Smith office was a dream come true. Both atmospherically speaking and in every other conceivable way. Prior to my arrival at The Smith, I had never been in the company of adults whose main objectives in life centered on poetry and writing, exclusively. This was another world entirely. One of good humor, too, I should add. Harry, himself, had a fine sense of humor. He and I laughed a lot together, practically non-stop. All sorts of people dropped by the office. Menke Katz, the first poet that I was ever introduced to. Novelist Clancy Sigal, just in, no doubt, from London (where he was based). Bob Reinhold, who wrote Stanley Kubrick’s first movie script. Harry knew a lot of people like Bob. Obscure writers and literary personalities that only a place like NYC could sustain in bulk. Practically within minutes of our meeting, Harry gave me keys to the amply cluttered two-room office to have copied so that I could let myself in and out; he also gave me mss. to read. I continued to read mss. throughout my time at The Smith as part of my job. (The absolutely infinite variety of typing styles and stationery was fascinating to me, by the way.) I was to put aside anything that might be of interest to Harry. News gathering for the muckraking THE NEWSLETTER (On the State of the Culture) was something that went on all of the time. If you are lucky enough to find copies of THE NEWSLETTER (in a university special collection, say), they form a uniquely excellent record of both mainstream and alternative publishing from that era. Essential, as well as being a tearjerker — that world is entirely vanished.

Biblioklept: I like that you bring up the mechanics, the physicality of working for a publisher — the “infinite variety of typing styles and stationery” — which I think plays a key part of Paperback Island. You talk about your first hand press, and how it allowed you to become a maker. Why do you think the physical experience of reading—of touching the material—has such an impact on some readers?

MB: Happily, I don’t really know the answer to your question. What Jessie Sheeler wrote about the “undiscoverable, inevitable prospect” of Caspar David Friedrich’s painting — in her discussion of Scottish poet Ian Finlay’s sea inscriptions — may have to suffice here: “not to be explained, but only acknowledged” (LITTLE SPARTA, THE GARDEN OF IAN HAMILTON FINLAY, Jessie Sheeler). Ever since 1995, when I edited a book about books, people have always 1) asked me what I think the fate of the physical book will be (short ans.: it will survive) and 2) shared with me how much it means to them to hold a book in hand. When I received the proof copy of PAPERBACK ISLAND I was thrilled to see it at long last, but it also felt a bit off. For one thing, it hadn’t bulked up in quite the way that I had anticipated. Come to find out, 30 or so pages were missing from the book. The corrected version arrived a few days later. I could tell without even opening the package that the book was as it should be — by its weight — it felt exactly right. Corrected, its spine is a good sixteenth of an inch wider. Within that fraction of difference (a 2.25 oz difference in terms of weight) dwells a better book, and not just because the missing pages have been restored. “Better proportions” Joseph Beuys might have said, who in 1964 once proposed elevating the Berlin Wall by 5 cm for just this reason. Beuys’s subversiveness aside, we live in a world where the Golden Ratio and like phenomena appear to count for something deep within us.

Biblioklept: What do you think about contemporary self-publishing?

MB: Regarding “self-publishing” — I am very glad that I came up when I did, when traditional publishing was unquestionably dominant and independent publishing was just about to manifest itself as a bona fide mass movement. (Another phenomenon of the 1970s, the proliferation of small presses. Compare the size of the 7th ed. of the INTERNATIONAL DIRECTORY OF LITTLE MAGAZINES & SMALL PRESSES, 1971-72, some 100 pp., to that of the 11th ed., 1975-1976, which is 304 pp. long. The 40th ed., 2004-05, is 790 pp.) My main concern regarding contemporary self-publishing is that it we may lose sight of the positive chemistry that can, in fact, exist between an author and a publisher. And who, really, keeps the designation “self-publishing” alive these days? I often wonder. Many people and businesses (including schools) who couldn’t be bothered with a small independent press — much less a self-published author — a few short years ago, are only too happy nowadays to service a prospective self-publishing author for a handsome fee.

One of my favorite publishing stories, ever, is as follows. Bern Porter, nuclear scientist, bibliographer, publisher, and promulgator of “founds” . . . for his Bern Porter Books listing in the DIRECTORY OF LITTLE MAGAZINES & SMALL PRESSES, 2004-2005, gave the founding year of his press as 1911 — his birth year. For the number of books his press published, or anticipated publishing: “467 titles 2003; expects 482 titles 2004, 493 titles 2005.” In the end, brilliant publishing is brilliant publishing.

Biblioklept: Growing up in the early nineties, there was this whole undergroundish traffick in zines, some professionally produced, some made via copy machines out of local 7-11 stores; a lot of the zines were connected to indie and punk music, but also comix and poetry and art. I love blogging and other internet platforms that allow for a “publication” of sort, but I sometimes wonder about the local connections that might be lost.

One of the things I like about Paperback Island is the evocation of place, of setting, of how physical places influence reading. The story about Susanna Cuyler letting you stay in her apartment so that you could read her book is really fascinating.

MB: You’ve hit the nail on the head — place is, in fact, important. Who can, for example, think of City Lights Books and not think of City Lights Bookstore and San Francisco? (When I was 16, I took a Greyhound Bus cross country from Boston, to see City Lights for myself. Incidentally, it was the first bookshop that I ever encountered that provided its own map for the purposes of navigating its offerings.) Likewise, Shakespeare & Co. and Paris. And on. One of the main reasons that I began submitting poetry to The Smith was that I was intrigued by its address: 5 Beekman St., NYC. (Quite a place it turns out — just Google it!). I believe that a good book sets you on an endless journey. So, these associative qualities are, in fact, critical. And, it seems to me, form the very foundation for a site such as Biblioklept’s. To come back to something that I said earlier, though, in the end it’s about people. And making connections with people.

As a bibliographic note, a master of celebrating place was Dick Higgins with his Something Else Press. Across bottom of Daniel Spoerri’s THE MYTHOLOGICAL TRAVELS OF A MODERN SIR JOHN MANDEVILLE (1970) the title page reads: “Something Else, Inc. / in New York City, by the Parking Lot of the Chelsea Hotel.” Locales would change from one Something Else title to another, by the way. Earlier, in 1968, the dateline read: “New York / Cologne / Paris.” Time, place, and beyond. Everything is possible. Dick was having his fun, but it was provocative, meaningful fun, too.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

MB: No, I have never stolen a book per se. Certainly not from a bookstore. I do have several library books that were never checked out — once upon a time, decades ago, back in college — for one reason or another (e.g., extreme laziness) and need to be returned. Of this I am guilty. (Guiltier than, apparently, Keith Richards, and his decades-overdue library books, which at least he bothered to check out as a youth. See the NY TIMES, 24 May 2013, p. C2.). I am terribly slow reader, by the way. I am still working my way through ULYSSES, the same copy that I bought in my teens in Liam O’Dell’s company, at the Book Clearing House in Boston. It took me years to get beyond the first page owing to the arresting Ernst Reichl typographic book design. To this day, I have never seen a display type letterpress “s” to match Reichl’s (full-page in size, as you may recall; appropriately enough, Leopold Bloom, himself, was knowledgeable about printing and the “specing” of type). On a distant note, the loaning of books and records to friends (and vice versa): I can’t think of anything finer. One of Life’s stronger points.