Near the end of the first cycle-section of Doris Lessing’s novel The Golden Notebook, protagonist Anna Wulf abandons the pretense of personal narrative in favor of pastiche, collage, clipping. Our heroine cuts and pastes material directly from the newspapers she’s been reading into her blue notebook:

[At this point the diary stopped, as a personal document. It continued in the form of newspaper cuttings, carefully pasted in and dated.]

March, 50

The modeller calls this the ‘H-Bomb Style’, explaining that the ‘H’ is for peroxide of hydrogen, used for colouring. The hair is dressed to rise in waves as from a bomb-burst, at the nape of the neck. Daily Telegraph.

July 13th, 50

There were cheers in Congress today when Mr Lloyd Bentsen, Democrat, urged that President Truman should tell the North Koreans to withdraw within a week or their towns would be atom-bombed. Express.

July 29th, 50

Britain’s decision to spend £100 million more on Defence means, as Mr Attlee has made clear, that hoped-for improvements in living standards and social services must be postponed. New Statesman.

Aug. 3, 50

America is to go right ahead with the H Bomb, expected to be hundreds of times more powerful than the atom bombs. Express.

The passages continue for pages in the same vein until:

30th March 2nd H-BOMB EXPLODED. Express.

This section of The Golden Notebook fits neatly into what I’ve come to think of as the Inhumanity Museum. The writer clips from the newspaper and passes those fragments to the author, who tosses them to the speaker, the narrator, a character, perhaps—and asks: What to do with these? Can you believe this? Are there even words for this?

Which is the appeal to the writer, I think, of clippings that belong to the Inhumanity Museum: That the journalist telegraphs (plainly, simply, succinctly) what the novelist may deem ineffable.

I’ve appropriated the term the Inhumanity Museum from William H. Gass’s novel Middle C:

The gothic house he and his mother shared had several attic rooms, and Joseph Skizzen had decided to devote one of them to the books and clippings that composed his other hobby: the Inhumanity Museum. He had painstakingly lettered a large white card with that name and fastened it to the door. It did not embarrass him to do this, since only he was ever audience to the announcement. Sometimes he changed the placard to an announcement that called it the Apocalypse Museum instead. The stairs to the third floor were too many and too steep for his mother now. Daily, he would escape his sentence in order to enter yesterday’s clippings into the scrapbooks that constituted the continuing record:

Friday June 18, 1999

Sri Lanka. Municipal workers dug up more bones from a site believed to contain the bodies of hundreds of Tamils murdered by the military. Poklek, Jugoslavia. 62 Kosovars are packed into a room into which a grenade is tossed. Pristina, Jugoslavia. It is now estimated that 10,000 people were killed in the Serbian ethnic-cleansing pogram..

There is more.

Tomato and Knife, Richard Diebenkorn

I’m still not sure exactly how the Inhumanity Museum fits into Middle C’s tale of fraud and music. Maybe it’s just Gass’s excuse to unload some of the material he’s been clipping for years. (Maybe I need to reread Middle C).

Here is Gass, in a 2009 interview, discussing William Gaddis (the emphasis is mine):

We were very close, even though we spent most of our time apart. I really had the warmest… We had great times. We both had the same views: Mankind, augh hsdgahahga!!!!. And he would read the paper and make clippings out of it. He was always saying, “Did you read…!?” We would both exalt in our gloom.

“Mankind [unintelligible]!” Ha! He would read the paper and make clippings out of it, like Pivner père in Gaddis’s novel The Recognitions, who builds his own Inhumanity Museum:

…he picked up his newspaper. The Sunday edition, still in the rack beside him, required fifty acres of timber for its “magic transformation of nature into progress, benefits of modern strides in transportation, communication, and freedom of the press: public information. (True, as he got into the paper, the average page was made up of a half-column of news, and four-and-one-half columns of advertising.) A train wreck in India, 27 killed, he read; a bus gone down a ravine in Chile, 1 American and 11 natives; avalanche in Switzerland, death toll mounts . . . This evening edition required only a few acres of natural grandeur to accomplish its mission (for it carried less advertising). Mr. Pivner read carefully. Kills father with meat-ax. Sentenced for slaying of three. Christ died of asphyxiation, doctor believes. Woman dead two days, invalid daughter unable to summon help. Nothing escaped Mr. Pivner’s eye, nor penetrated to his mind; nothing evaded his attention, as nothing reached his heart. The headless corpse. Love kills penguin. Pig got rheumatism. Nagged Bible reader slays wife. “Man makes own death chair, 25,000 volts. “Ashamed of world,” kills self. Fearful of missing anything, he read on, filled with this anticipation which was half terror, of coming upon something which would touch him, not simply touch him but lift him and carry him away.Every instant of this sense of waiting which he had known all of his life, this waiting for something to happen (uncertain quite what, and the Second Advent intruded) he brought to his newspaper reading, spellbound and ravenous.

There is more.

This section of The Recognitions reminds me of Félix Fénéon’s faits divers, microtragedies composed in 1906 for the newspaper Le Matin:.

“If my candidate loses, I will kill myself,” M. Bellavoine, of Fresquienne, Seine-Inferieure, had declared. He killed himself.

A thunderstorm interrupted the celebration in Orléans in honor of Joan of Arc and the 477th anniversary of the defeat of the English.

In the course of a heated political discussion in Propriano, Corsica, two men were killed and two wounded.

In Bone, the courts and the bar have reestablished contact with the prison, now that the typhus outbreak there has been curbed.

Clash in the street between the municipal powers of Vendres, Herault, and the party of the opposition. Two constables were injured.

Despondent owing to the bankruptcy of one of his debtors, M. Arturo Ferretti, merchant of Bizerte, killed himself with a hunting rifle.

Etc.

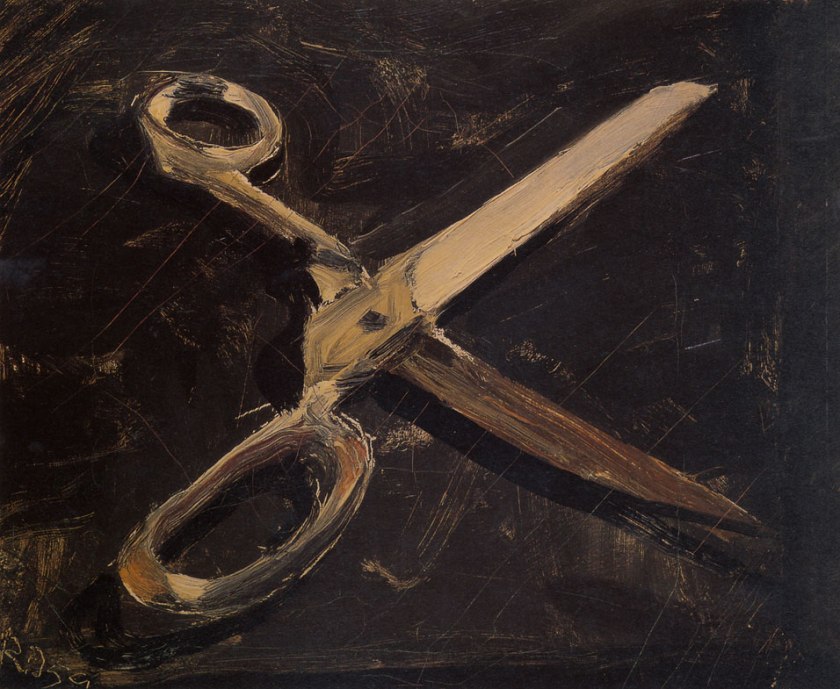

Scissors and Lemon, Richard Diebenkorn

Fénéon’s faits divers owe their survival to scissors and paste: His mistress cut each column from the paper and collected them in an album. A century later, NYRB published Novels in Three Lines, their own album of Fénéon’s faits divers.

Recently, the writer Teju Cole has followed Fénéon’s example, composing his own series of small fates. Cole began his small fates while working on his “new book, a non-fictional narrative of Lagos.” Cole’s small fates had their origin in the crime and metro sections of the Nigerian newspapers that he read daily. Attracted to the “life in the raw” presented here, Cole revised the news articles into a synthesis of Fénéon’s style with his own. He felt that these stories were “too brief, too odd, and certainly too sensational” for his new book, and yet he was compelled to tell them anyway. Even if he couldn’t fit them into his new book, they were nevertheless part of his storytelling project.

Fénéon was elevating a preexisting form of newspaper reporting, artfully injecting humor and subtle observation into the structure of his faits divers, unlike Lessing, Gaddis, or Gass, who used clippings to inject reality—and the real human inhumanity of reality—into their fictional texts.

Perhaps Fénéon was motivated by the same spirit as those later authors. Perhaps like Pivner the Elder in Gaddis’s The Recognitions “the newspaper served him, externalizing in the agony of others the terrors and temptations inadmissible in himself.” There’s something defensive about the humor in Fénéon’s faits divers, a human reaction to horror we misname inhuman.

Is there another way to react? In her short story “Greenleaf,” Flannery O’Connor converts the Inhumanity Museum into a strange, private shrine. Mrs. Greenleaf (whom the protagonist Mrs. May regards with utter contempt) buries her clippings and prays over them:

Instead of making a garden or washing their clothes, her preoccupation was what she called “prayer healing.” Every day she cut all the morbid stories out of the newspaper—the accounts of women who had been raped and criminals who had escaped and children who had been burned and of train wrecks and plane crashes and the divorces of movie stars. She took these to the woods and dug a hole and buried them and then she fell on the ground over them and mumbled and groaned for an hour or so, moving her huge arms back and forth under her and out again and finally just lying down flat and, Mrs. May suspected, going to sleep in the dirt.

The opening lines suggest an ironic displacement. Mrs. May, a thoroughly worldly figure, devoid of spirituality, thinks that Mrs. Greenleaf should be “making a garden or washing,” activities we might associate with a kind of spiritual activity—Eden-building or purifying (for Mrs. May these would be quotidian chores). Mrs. Greenleaf’s prayer healing is of course explicitly spiritual, but its spirituality directly responds to the awful lurid everyday morbidity of the news.

O’Connor doesn’t use the same (in)direct cut and paste technique as some of the other writers I’ve mentioned here, but her fiction is full of newspaper and magazine readers. I think now of Bailey, the ill-fated father in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” whom we meet “bent over the orange sports section of the Journal.” There’s something lurid about the orangeness, a bright distraction. (In O’Connor’s universe The Holy Bible is the book everyone evades contemplating). And it’s in that same paper that the Misfit is introduced, the serial killer who brings the characters from distraction back to reality.

For O’Connor, the stakes couldn’t be higher—she was concerned for the immortal soul:

…in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work. This idea, that reality is something to which we must be returned at considered cost, is one which is seldom understood by the casual reader, but it is one which is implicit in the Christian view of the world.

While O’Connor was deeply invested in her own “Christian view of the world,” I think she offers a description, if not a definition, of how the Inhumanity Museum can function in literary texts. It’s the violent shock of the real that the author wishes to evoke. The utter banality of how that reality is communicated through mass texts serves to bring the shock into sharper relief.

Is the goal then to unlearn the dulled reading habits that Gaddis showcases in Pivner?: “Nothing escaped Mr. Pivner’s eye, nor penetrated to his mind; nothing evaded his attention, as nothing reached his heart.” Yet to be so fully absorbed into the pain and ugliness and stupidity of the world would surely result in crushing madness, or “chaos,” as Anna Wulf of The Golden Notebook claims. And perhaps that’s why the Inhumanity Museum is such an important location. A museum has an exit.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally published this post in August, 2014].