In trying to frame a review of S.D. Chrostowska’s novel Permission, I have repeatedly jammed myself against many of the conundrums that the book’s narrator describes, imposes, chews, digests, and synthesizes for her reader.

I have, for example, just now resisted the impulse to place the terms novel, narrator, and reader under radical suspicion. (I realize that the last sentence carries out the impulse even as it purports not to). Permission, thoroughly soaked in deconstruction, repeatedly places its own composition under radical suspicion.

This is maybe a bad start to a review.

Another description:

Permission pretends to be the emails that F.W. (later F. Wren, and even later, Fearn Wren) sends to an unnamed artist, a person she does not know, has never met, whom she contacts in a kind of affirmation of reciprocity tempered in the condition that her identity is “random and immaterial.” She aims to work out “an elementary philosophy of giving that is, by its very definition, anti-Western.” Her gift is the book she creates — “Permit me to write to you, today, beyond today,” the book begins.

Why?

What I want to measure—or, rather, what I want to obtain an impression of, since I do not claim exactitude of measurement for my results—is my own potential for creatio ad nihilum (creation fully within the limits of human ability, out of something and unto nothing). To rephrase my experimental question: can I give away what is inalienable from me (my utterance, myself) without the faintest expectation or hope of authority, solidarity, reciprocity?

F.W.’s project (Chrostowska’s project) here echoes Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction of giving, of the (im)possibility of authentic giving. F.W. wants to give, but she also deconstructs that impulse repeatedly. This is a novel (novel-essay, really) that cites Gilles Deleuze and Maurice Blanchot in its first twenty pages.

Her project is deconstruction; as she promises at the outset, her giving, her writing “is not solid, and does not lead to solidarity.” On the contrary,

it is solvent, and leads, through its progressive dissolution, towards the final solution of this writing (my work), which meanwhile becomes progressively less difficult, less obscure.

“Will it?” I asked in the margin of my copy. It does, perhaps.

After an opening that deconstructs its own opening, Chrostowska’s F.W. turns her attention to more concrete matters. We get a brief tour of cemeteries, a snapshot of the F.W.’s father (as a child) at a child’s funeral, a recollection of her first clumsy foray into fiction writing, a miniature memoir of a failed painter, color theory, the sun, the moon. We get an overview of our F.W.’s most intimate library—The Hound of the Baskervilles, a samizdat copy of Listy y Bialoleki [Letters from Bialoleka Prison], 1984. We get an analysis of Philip Larkin’s most famous line. Prisons, lunatic asylums, schools. Indian masks. Hamlet. More cemeteries.

My favorite entry in the book is a longish take on the “thingness of books,” a passage that concretizes the problems of writing—even thinking—after others. I think here of Blanchot’s claim that, ” No sooner is something said than something else must be said to correct the tendency of all that is said to become final.”

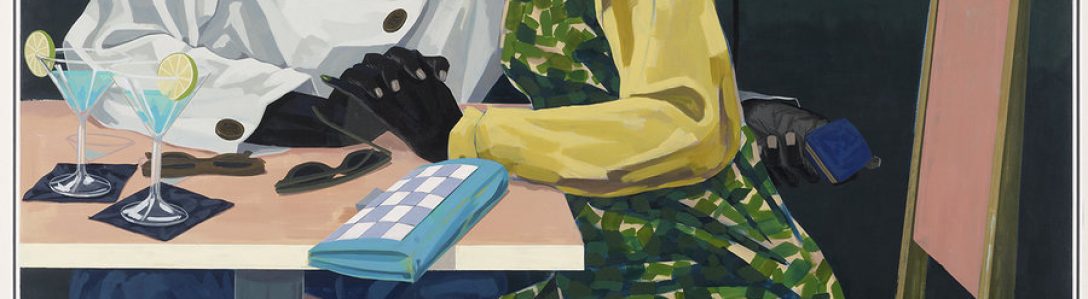

The most intriguing passages in Permission seem to pop out of nowhere, as Chrostowska turns her keen intellect to historical or aesthetic objects. These are often accompanied by black and white photographs (sometimes gloomy, even murky), recalling the works of W.G. Sebald, novel-essays that Permission follows in its form (and even tone). Teju Cole—who also clearly followed Sebald in his wonderful novel Open City—provides the blurb for Permission, comparing it to the work of Sebald’s predecessors, Thomas Browne and Robert Burton. There’s a pervasive melancholy here too. Permission, haunted by history, atrocity, memory, and writing itself, is often dour. The novel-essay is discursive but never freewheeling, and by constantly deconstructing itself, it ironically creates its own center, a decentered center, a center that initiates and then closes the work—dissolves the book.

Permission, often bleak and oblique, essentially plotless (a ridiculous statement this, plotless—this book is its own plot (I don’t know if that statement makes any sense; it makes sense to me, but I’ve read the book—the book is plotless in the conventional sense of plotedness, but there is a plot, a tapestry that refuses to yield one big picture because its threads must be unthreaded—dissolved to use Chrostowska’s metaphor)—where was I?—Yes, okay, Permission, as you undoubtedly have determined now, you dear, beautiful, bright thing, is Not For Everyone. However, readers intrigued by the spirit of (the spirit of) writing may appreciate and find much to consider in this deconstruction of the epistolary form.

Permission is new from The Dalkey Archive.

I once saw Jacques Derrida speak for several hours on the question of whether his death was possible. I believe this was back around 1994 or so.

LikeLike

I see. Thank you for informing me.

LikeLike

[…] Permission, S.D Chrostowska […]

LikeLike

[…] I interviewed S.D. Chrostowska for 3:AM Magazine. I reviewed Chrostowska’s novel Permission here. […]

LikeLike