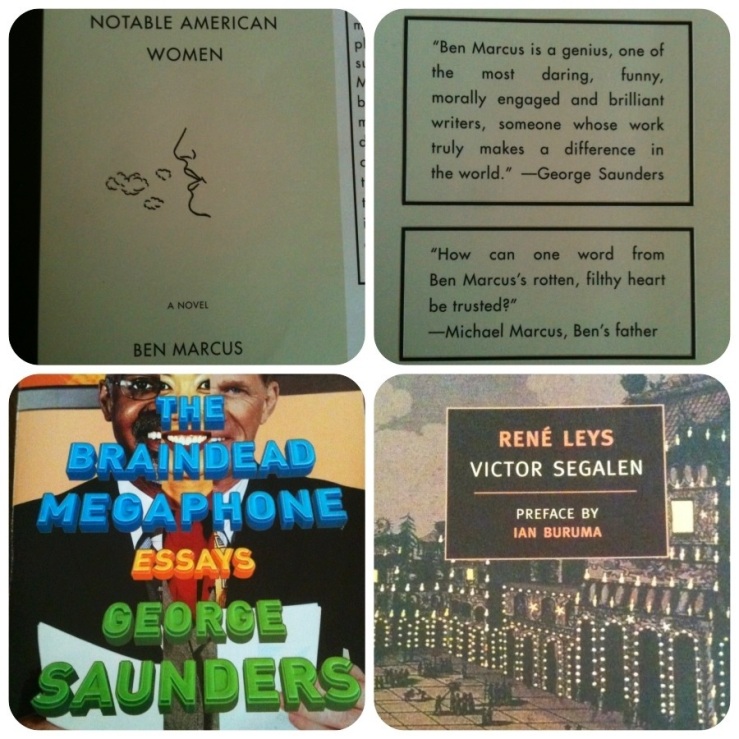

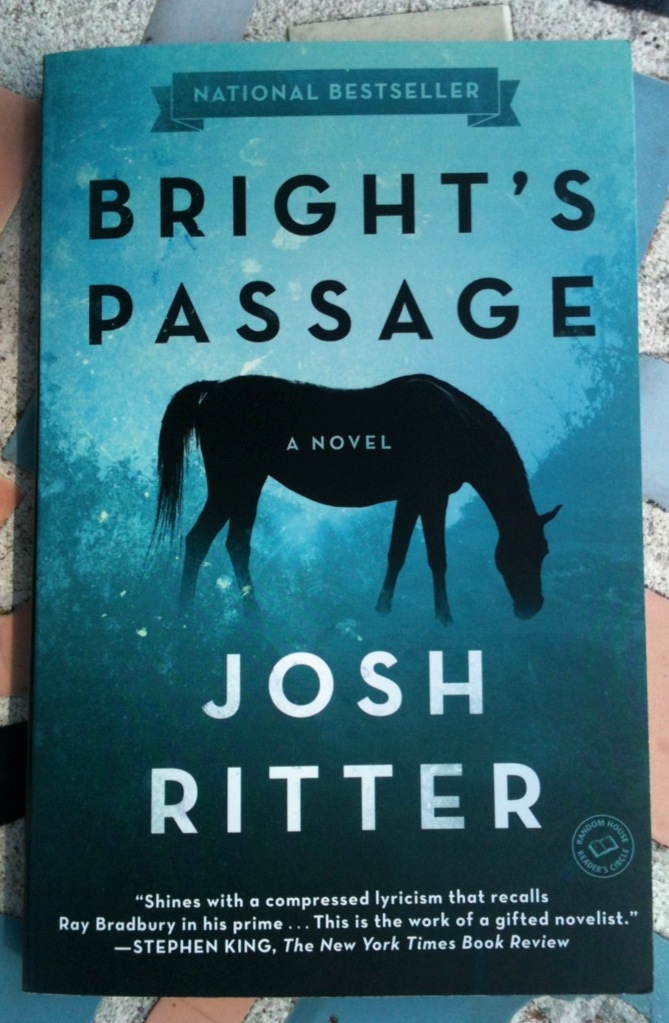

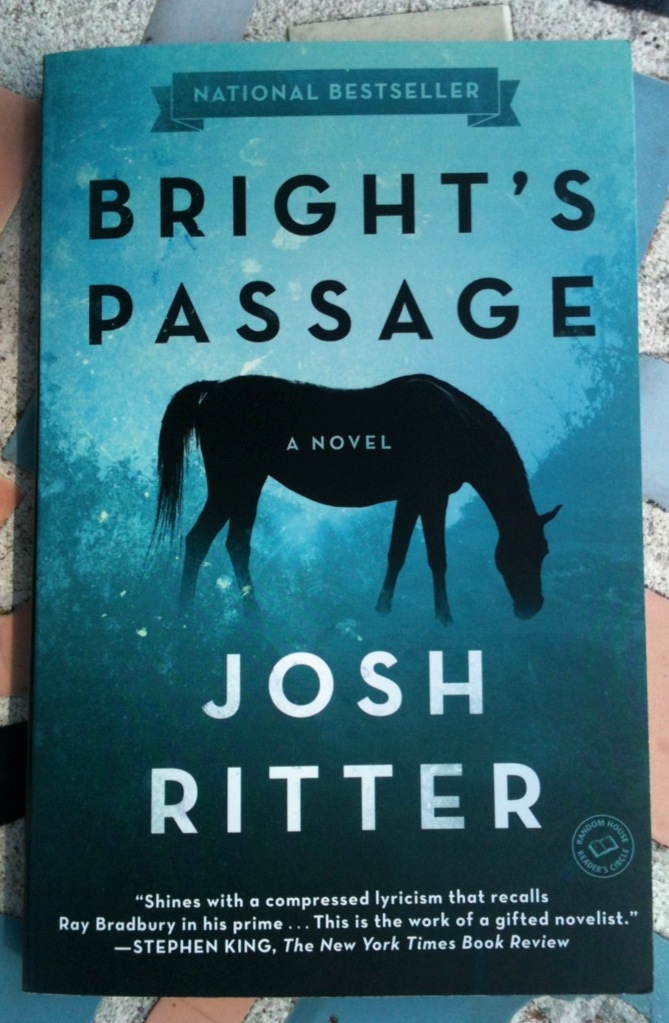

Josh Ritter’s Bright’s Passage is out in trade paperback, featuring a Q&A at the end with Ritter and some guy named Neil Gaiman who used to write comic books or something. Here’s my write up from last year, wherein I quote some guy named Stephen King:

Bright’s Passage is the début novel from songwriter/musician Josh Ritter. This slim novel tells the story Henry Bright, a man who returns to the hills of West Virginia after the trauma of World War I only to have his wife (who is also his first cousin) die in childbirth. Bright buries her body and sets fire to their cabin, which sparks a massive forest fire. Bright then takes his infant son and flees, both from the fire and his unstable father-in-law, “The Colonel,” a vet of America’s adventures in the Philippines who still wears his uniform. The Colonel and his crazy sons pursue Bright, who is guided on the lam by the angel who talks to him—yeah, an angel directs Bright; in fact it was the angel’s idea that Bright marry his cousin, burn down his cabin, and run . . . also, the angel swears that Bright’s son is going to be, like, the new Messiah. Also, Bright’s horse talks. Ritter moves the action between Bright’s flight, his ordeal in WWI, and his youth in simple, concrete, declarative prose. There are echoes here of Chris Adrian’s angel stories (The Children’s Hospital and A Better Angel), and perhaps something of a Cormac McCarthy-lite vibe. Here’s an excerpt from obscure author Stephen King’s review in the Times—

At its best, “Bright’s Passage” shines with a compressed lyricism that recalls Ray Bradbury in his prime. When Henry, his talking horse — a kind of holy Mr. Ed — and the Future King of Heaven leave the woods and enter a small town, Ritter writes: “It seemed a tidy place of dappled white houses and American flags. . . . Even the trees here seemed to have a kind of deep green and prepossessing prosperity that the trees of the forest could have no share in.” Recalling his mother’s death, Henry remembers “a windstorm that made the trees bow to one another like ballroom dancers.” More striking still are Henry’s memories of life in the trenches, some of which compare favorably to the prose in Mark Helprin’s “Soldier of the Great War”: “Artillery passed high above their heads in singsong trajectories that merged and lifted with one another into strange musical chords, like cats crossing pump organs.”

And here’s a tomato from my spring garden:

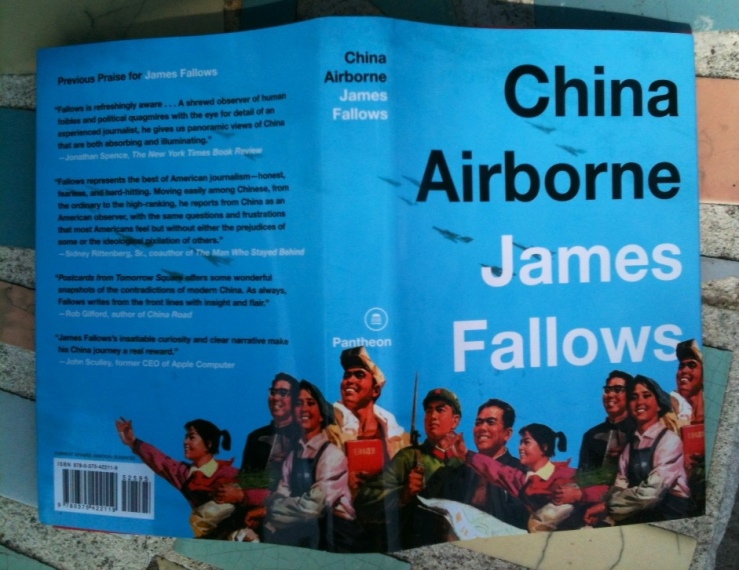

Nice cover on China Airborne, a book about the rise of Chinese industry by James Fallows. Pantheon’s write up:

More than two-thirds of the new airports under construction today are being built in China. Chinese airlines expect to triple their fleet size over the next decade and will account for the fastest-growing market for Boeing and Airbus. But the Chinese are determined to be more than customers. In 2011, China announced its Twelfth Five-Year Plan, which included the commitment to spend a quarter of a trillion dollars to jump-start its aerospace industry. Its goal is to produce the Boeings and Airbuses of the future. Toward that end, it acquired two American companies: Cirrus Aviation, maker of the world’s most popular small propeller plane, and Teledyne Continental, which produces the engines for Cirrus and other small aircraft.

In China Airborne, James Fallows documents, for the first time, the extraordinary scale of this project and explains why it is a crucial test case for China’s hopes for modernization and innovation in other industries. He makes clear how it stands to catalyze the nation’s hyper-growth and hyper- urbanization, revolutionizing China in ways analogous to the building of America’s transcontinental railroad in the nineteenth century. Fallows chronicles life in the city of Xi’an, home to more than 250,000 aerospace engineers and assembly workers, and introduces us to some of the hucksters, visionaries, entrepreneurs, and dreamers who seek to benefit from China’s pursuit of aerospace supremacy. He concludes by examining what this latest demonstration of Chinese ambition means for the United States and the rest of the world—and the right ways to understand it.

Some not-quite-ripe blackberries from my garden:

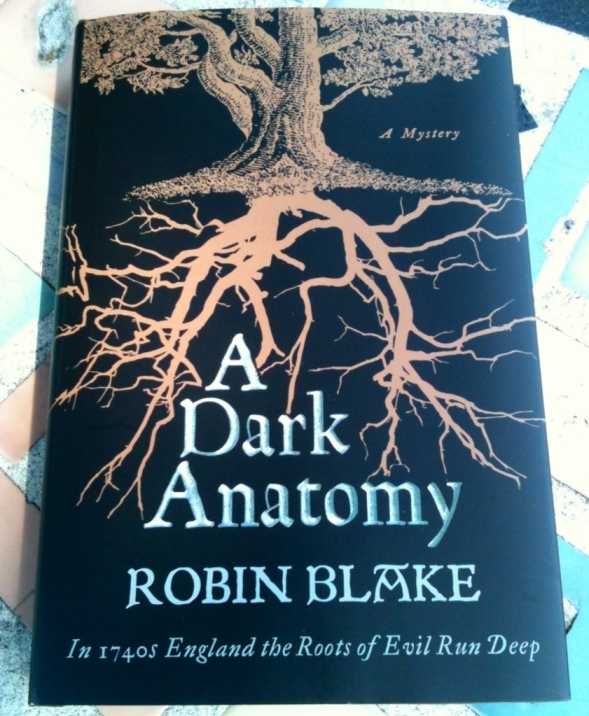

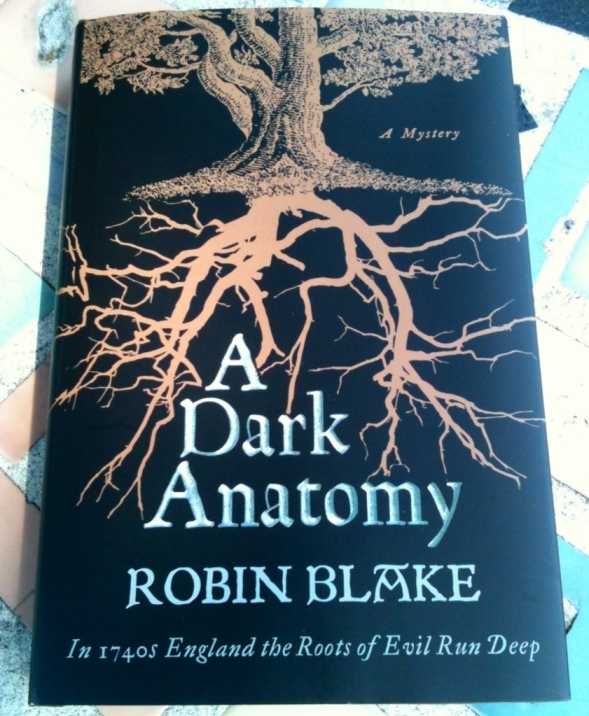

I like the cover on this one too, a historical mystery by Robin Blake called A Dark Anatomy (and I know someone who might like this book for a present). From Blake’s site:

Mid-Georgian Preston was one of England’s ancient self-governing charter towns, pleasantly and strategically located in the heart of Lancashire, with a thriving agricultural market, and a significant concentration of craft workers amongst its stable population of below 5,000. In the 1600s the town gradually became Lancashire’s prime social and legal centre, and remained so until industrialization transformed and disfigured the town at the end of the century, turning it into the grimy and overcrowded manufactory that Charles Dickens called Coketown, the setting for Hard Times. Today hardly anything pre-Victorian remains except the medieval street-plan around the central area: the three principle streets of Church Gate (now Church Street), Friar Gate and Fisher Gate, leading away from the focal point of the flagged market and the site of the old timber-framed Moot Hall, where a 1960s office block of remarkable ugliness now stands.

Politically, like most other borough towns, Georgian Preston was an oligarchy. The council’s 24 members (or burgesses) appointed each other and parceled out the senior offices, including the Mayor and two Bailiffs, annually between themselves. Charter towns like this were virtual city-states where (in Tom Paine’s scathing words) a man’s “rights are circumscribed to the town and, in some cases, to the parish of his birth; and all other parts, though in his native land, are to him as a foreign country”. These communities reserved the right to run their own affairs, and keep outsiders away at all costs.

I take a few liberties with details of local administration, not least in the Coroner’s office. In historical Preston the unusual custom was for the annually appointed Mayor to sit as Coroner ex officio. But I wanted my investigator to stand apart from local politics, so I have imposed the more usual model whereby the Coroner was a Crown appointment with life-tenure, and independent of the Corporation. My other inventions in A Dark Anatomy include Garlick Hall, the nearby village of Yolland, and most of the cast of characters.

And here’s a white eggplant from my garden: