Top to bottom:

I am a huge fan of Atticus Lish’s 2014 novel Preparation for the Next Life, and I’m a fan of indie Tyrant Books, but I’d never heard of his 2011 collection of doodles, Life Is With People. The book wasn’t even shelved properly yet, and I was initially attracted to its strange pink and black cover. It turned out the bookseller who checked out my purchases that day (the Lish and some books for my son) had brought the Lish in; his interest in it was in Lish-as-son-of-Lish. We chatted about Barry Hannah a bit and I recommended he read Hob Broun, which I recommend to anyone who expresses admiration for Hannah or Father Lish.

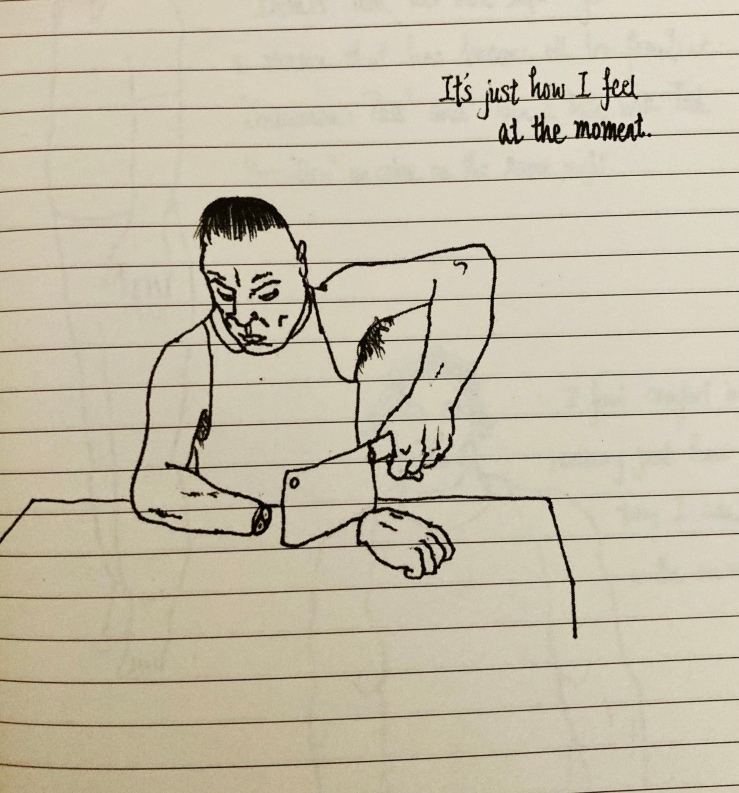

Here is one of the cartoons from Lish’s collection:

This particular cartoon is probably my favorite in the collection, as I find it the most relatable.

In a lovely bit of serendipity, I happened upon a first edition hardback copy of Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel Poor Things. The previous day, I had pulled out my paperback copy to reread it in anticipation of Yorgos Lanthimos film adaptation. I ended up reading the old paperback copy, already somewhat battered, highlighted (not mine!) and dogeared (mine…), and had initially planned to trade it in toward future hardback editions of books I already own, which seems like my mission these days, but my son expressed his desire to read the novel, so it’s his I guess.

The book sans jacket is gorgeous too:

I finished Poor Things before Thanksgiving, and should have Something on it on this blog in the next week or so.

I’ve brought my son up a few times in my riff—most of these November bookstore trips were in his company; twice because he showed his art at one of the bookstore’s location, and once (the most recent, the Gray acquisition) because he’s reading like a maniac. I’m frankly jealous of how he’s reading right now—fast, somewhat indiscriminately, but with designs on reading what he calls “You know, the classics.” Initially he was reading old mass market paperbacks of mine — Kurt Vonnegut, Albert Camus, John Gardner — but he wanted his own copies (“I need to start my own little library, right?”).

I couldn’t pass up the first editions of Gass’s Middle C or Powers’ The Gold Bug Variations. I knew that I no longer had a paperback copy of The Gold Bug Variations, having loaned it to a colleague years ago who moved to Norway in the middle of a semester, leaving her history department scrambling to cover classes. Maybe it’s in Norway. I did think I had a copy of Gass’s Middle C, but I must’ve checked it out from the library or lost it, or maybe it’s shelved behind other books. I’ll shelve it by The Tunnel, a reminder that I need to take one more shot at that beast. And if that one shot is not sufficient, another shot I will take…