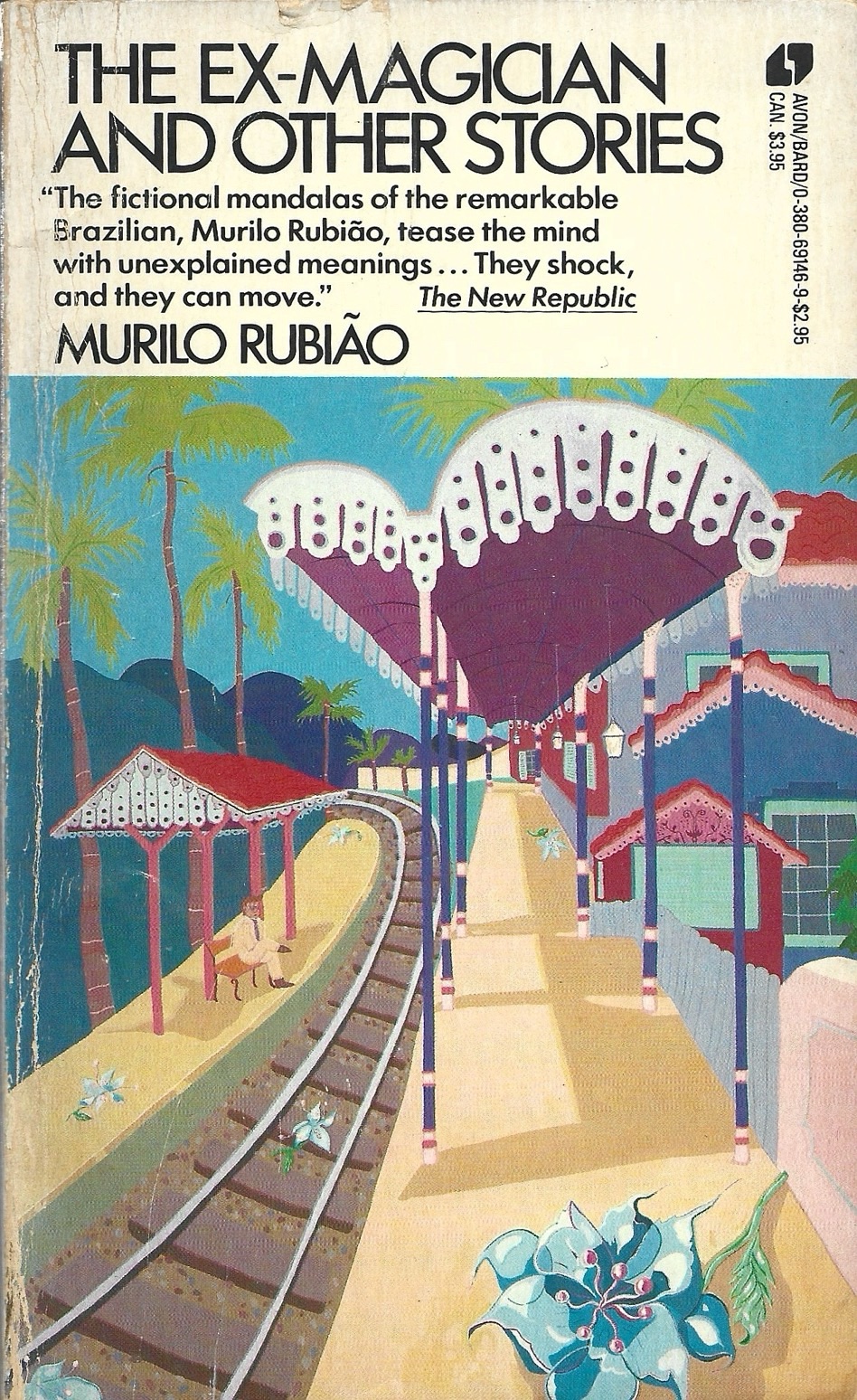

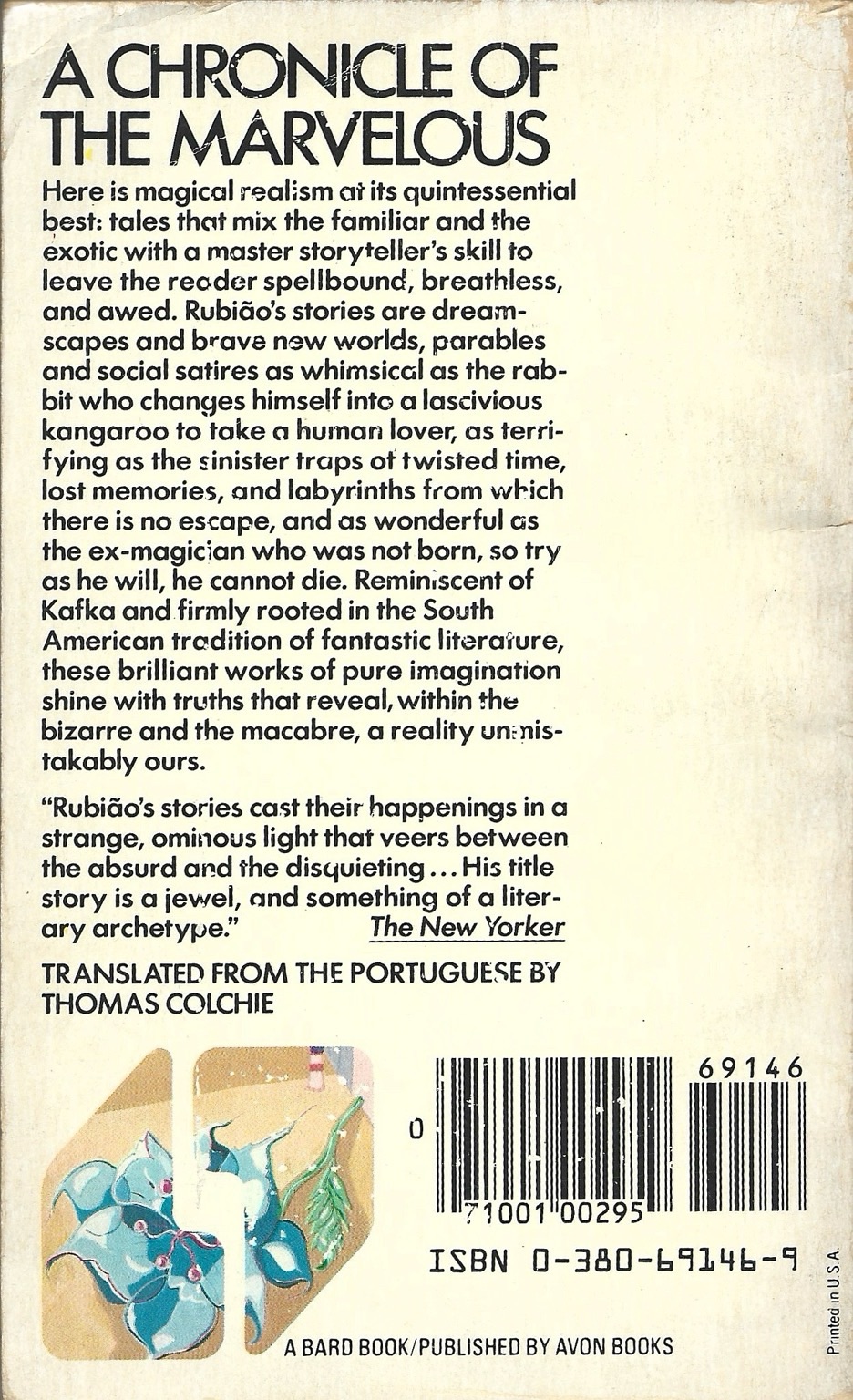

The Ex-Magician and Other Stories, Murilo Rubião, 1979. Translation by Thomas Colchie. Avon-Bard (1984). No cover artist or designer credited. 119 pages.

“Elisa”

by

Murilo Rubião

Translation by Thomas Colchie

I love them that love me; and those that seek me early shall find me.

Proverbs, VIII:17

One afternoon—it was in the early days of April—she arrived at our home. She pushed open the gate quite naturally, which guarded our little front yard, as if she were simply obeying a time-worn habit. From up on the porch, where I was sitting, a needless observation slipped out:

“And what if we had a dog?”

“Dogs don’t frighten me,” she replied wearily.

With a certain difficulty (the suitcase she was carrying must have been quite heavy) she managed to climb the stairs. Before going in, at the front door she turned to me:

“Or men either.”

Surprised by her capacity to divine my thoughts, I made haste to extricate myself from what seemed to be an increasingly embarrassing situation:

“Terrible weather out today. If it goes on like this …”

I cut short the series of absurdities that now occurred to me and tried, rather awkwardly, to avoid her look of reproach.

Then she smiled a little, while I nervously squeezed my hands.

Our strange visitor quickly adjusted to the ways of the house. She seldom went out, and never appeared at the window.

Perhaps at first I hadn’t even noticed her beauty: so lovely, even when the spell was broken, with her half-smile. Tall, her skin so white, but such a pale white, almost transparent, and a gauntness that betrayed a profound degradation. Her eyes were brown, but I don’t wish to talk of them. They never left me.

She soon began to fill out more, to gain some coloring and, in her expression, to display a joyful tranquillity.

She didn’t tell us her name, where she came from, or what terrible events had so shaken her life. In the meantime, we respected her silence on such matters. To us, she was simply herself: someone who needed our care, our affection.

I was able to accept the long silences, the sudden questions. One night, without my expecting it, she asked me:

“Have you ever loved?”

When the answer was in the negative, she made obvious her disappointment. After a while she left the sitting room, without adding a word to what she had spoken. The next morning we discovered her room was empty.

Every afternoon, as dusk was about to fall, I would step out onto the porch, with the feeling that she might show up, any moment, at the corner. My sister Cordelia berated me:

“It’s useless, she won’t be back. If you were only less infatuated, you wouldn’t be having such hopes.”

A year after her flight—again it was April—she appeared at the front gate. Her face was sadder, with deep shadows under the eyes. In my own eyes, so overjoyed to see her, the tears welled up, and in an effort to provide her with a cordial reception I said:

“Careful, now we do have a little dog.”

“But her master is still gentle, isn’t he? Or has he turned fierce during my absence?”

I extended my hands, which she held for a long time. And then, no longer able to suppress my concern, I asked her:

“Where did you go? What have you done all this time?”

“I wandered around and did nothing. Except maybe love a little,” she concluded, shaking her head sadly.

Her life among us returned to its former pace. But I felt uneasy. Cordélia observed me pityingly, implying I should no longer conceal my passion.

I lacked, however, the courage, and so put off my first declaration of love.

Several months later Elisa—yes, she finally told us her name—departed again.

And since I was left knowing her name, I suggested to my sister we should move to a different place. Cordélia, although extremely attached to our house, raised no objection and limited herself to asking:

“And Elisa? How will she be able to find us when she returns?”

I managed, with an effort, to conceal my anxiety, and repeated like an idiot:

“Yes, how will she?”