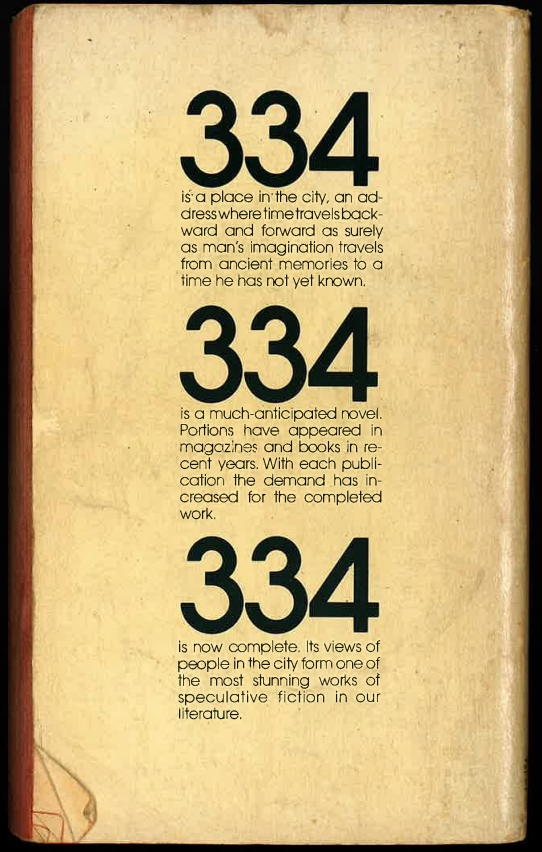

334, 1972, Thomas M. Disch. Avon Bard (1974). No cover designer or artist credited. 269 pages.

Disch’s dystopian novel 334 is comprised of five separate but related novellas. The stories are set in and around the year 2025. Here’s “The Teevee,” the first vignette of the last novella in the collection, 334:

“The Teevee (2021)”

Mrs. Hanson liked to watch television best when there was someone else in the room to watch with her, though Shrimp, if the program was something she was serious about—and you never knew from one day to the next what that might be—, would get so annoyed with her mother’s comments that Mrs. Hanson usually went off into the kitchen and let Shrimp have the teevee to herself, or else to her own bedroom if Boz hadn’t taken it over for his erotic activities. For Boz was engaged to the girl at the other end of the corridor and since the poor boy had nowhere in the apartment that was privately his own except one drawer of the dresser they’d found in Miss Shore’s room it seemed the least she could do to let him have the bedroom when she or Shrimp weren’t using it.

With Boz when he wasn’t taken up with l‘amour, and with Lottie when she wasn’t flying too high for the dots to make a picture, she liked to watch the soaps. As the World Turns. Terminal Clinic. The Experience of Life. She knew all the ins and outs of the various tragedies, but life in her own experience was much simpler: life was a pastime. Not a game, for that would have implied that some won and others lost, and she was seldom conscious of any sensations so vivid or threatening. It was like the afternoons of Monopoly with her brothers when she was a girl: long after her hotels, her houses, her deeds, and her cash were gone, they would let her keep moving her little lead battleship around the board collecting her $200, falling on Chance and Community Chest, going to Jail and shaking her way out. She never won but she couldn’t lose. She just went round and round. Life.

But better than watching with her own children she liked to watch along with Amparo and Mickey. With Mickey most of all, since Amparo was already beginning to feel superior to the programs Mrs. Hanson liked best—the early cartoons and the puppets at five-fifteen. She couldn’t have said why. It wasn’t just that she took a superior sort of pleasure in Mickey’s reactions, since Mickey’s reactions were seldom very visible. Already at age five he could be as interior as his mother. Hiding inside the bathtub for hours at a time, then doing a complete U-turn and pissing his pants with excitement. No, she honestly enjoyed the shows for what they were—the hungry predators and their lucky prey, the good-natured dynamite, the bouncing rocks, the falling trees, the shrieks and pratfalls, the lovely obviousness of everything. She wasn’t stupid but she did love to see someone tiptoeing along and then out of nowhere: Slam! Bank! something immense would come crashing down on the Monopoly board scattering the pieces beyond recovery. “Pow!” Mrs. Hanson would say and Mickey would shoot back, “Ding-Dong!” and collapse into giggles. For some reason “Ding-Dong!” was the funniest notion in the world.

“Pow!”

“Ding-Dong!” And they’d break up.