Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Chapter 15 opens proximal to Xmas time, presumably 1931, still–although it’d take a reread for me to pin down the timeline better. Hicks is in the grip of mild paranoia, feeling like he’s the target of some unknown They. The feeling is a haunting: “light as delusional bugs, the ghostly crawl of professional finger-eye coordination, somewhere above and in the distance, tightening in on whatever is centered in its crosshairs, which at the moment happens to be Hicks’s head.”

Hicks’s paranoia is well-placed. He’s “handed a parcel wrapped in festive red-and-green paper whose design features Xmas trees, reindeer, candy canes, so forth. Ribbon tied in a big bow. Something to do with Christmas” by miscreants claiming to be “Santa’s elves.”

Skeptical Hicks denies the supernatural, natch, despite the “ghostly crawl” that’s come over his aspect this haunted season. The so-called elves protest that they are cousins of Billie the Brownie, an historical mainstay of Milawaukee’s Schuster’s Department Store Christmas spectacles.

(I’ve tried not to overload these riffs with too many of Pynchon’s Milwaukee/Milwaukee-proximal references–like, I couldn’t leave Les Paul out when I riffed on Ch. 8, but I didn’t include his reference in the same chapter to Árpád Élő, the Hungarian-American physicist who taught at Marquette in Milwaukee for four decades, during which time he developed the Elo chess rating. Anyway, the point is — for a breezy novel, Shadow Ticket is still pretty dense. Pynchon enjoys fat in the right proportion.)

Anyway, addressing Hicks as “Schultz,” the elves deliver an Xmas package and evaporate into thin air. Then who appears? “Damn if it ain’t the same sawed-off Bolshevik striker Hicks didn’t manage to kill that fateful night not so long ago,” who we learned of back in Ch. 4 (recall Hicks felt some kind of metaphysical interjection prevented his striking down the protester). He warns Hicks to dispose of the package posthaste, insinuating it’s a time bomb.

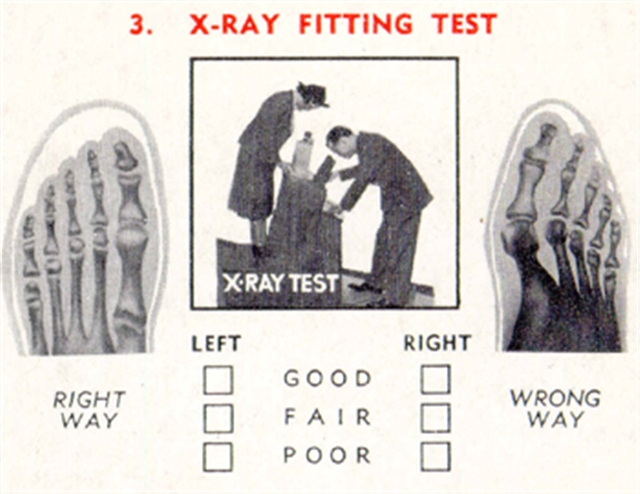

Hicks steps into Wisebroad’s Shoes in order to use their, yes, X-ray machine. The narrator informs us that, “One of many interesting facts about Milwaukee is that along with the Harley-Davidson motorcycle and the QWERTY typewriter keyboard layout, it’s also the birthplace of the shoe-store X-ray machine.” I have to admit I thought at first that the ridiculousness of such an apparatus struck me as a goofy Pynchonian invention. But shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were like a totally real twentieth-century thing. (One of the shoe clerks attests that he prefers Brannock devices as X-rays “don’t pick up fat, and fat’s the key, see.”)

The X-ray riff here ties into Shadow Ticket’s themes of mad science, glow-in-the-dark wonders, and strange rays, like those Dr. Swampscott Vobe was said to experiment on his psychiatric patients (Ch. 14) or the irradiated “Radio-Cheez” that helped establish the Airmont cheese fortune (Ch. 13).

Instead of a bomb in the package, Hicks and the shoe clerks see something closer to a face when they peer into the fluoroscope’s lens. The scene is another moment of anxious dread, horror even, woven into the comic zaniness:

“Despite a certain blurriness, Hicks realizes it is inescapably a face, not unchanging and lifeless, like you’d get from a severed head for example, but instead gazing back with its eyes wide open and holding a gleam of recognition, a face he’s supposed to know but doesn’t, or at least can’t name. Mouth about to open and tell him something he should’ve known before this. The window he never wanted to have to look through, the bar he used to know enough not to set foot inside of.”

Hicks disposes of the package in Lake Michigan, where it explodes.

Later, Hicks, haunted and depressed, finds some solace in April. But they both know he won’t keep the girl, even as he dreams of them as partners on the move, “teamed up against each day and its troubles.”

The chapter ends with Hicks trying to pick up the thread of why those elves delivered the bomb to him, and why they called him Schulz. Uncle Lefty isn’t really much help. Hick checks in with the anarchist bombsmith Michele “Kelly” Stecchino, a character who could fit in neatly in Against the Day. Kelly suggests that “an explosion, not always but sometimes, is actually somebody with something to say. Like, a voice, with a message we aren’t receiving so much as overhearing.” He then advises Hicks to get out of town, suggesting a trip to Italy. Hicks protests that Italy’s, “Fascist dictatorship, Professore,” and anarchist Kelly needles him back, asking “What makes you private dicks any different?…Study your history, gabadost, you started off, mosta yiz, breakin up strikes, didn’t ya, same as Mussolini’s boys.” Again, one of the major conflicts in Shadow Ticket is Hicks realizing which side of history he wishes to be on. Hicks then checks in at the Nazi bolwing alley, New Nuremberg Lanes with his old associate Ooly, who thinks that the bomb “don’t feel local. Somethin’s on the way around here, bigger than a gang war.” That would be a World War. Finally, Hicks checks in with Lew Basnight (who was in Against the Day); Lew tells him that what he’s “after is an Overlooked Negative.” Is that something an X-ray could catch? Hicks tells Lew that he was “always what I was hoping to be someday” — and I don’t think he meant it as mere flattery.

Chapter 16 sees the action move out from Milwaukee (much to Hicks’s chagrin). His employer seems to agree with everyone else that he should get out of town for his own health and safety, and the agency sends him to New York (Hicks picks up on the fact that his travel stipend is decidedly a one way sum).

April’s gangster beau Don Peppino sends one of his enforcers along too to suggest he hits the bricks. (The goon tries to hip Hicks to how one might take a “grape so harsh and bitter you’d never make wine from it alone—but when you blend it with other grapes, sometimes only a couple percent, suddenly a miracle” — but Hicks protests that he’s “Only a beer drinker.” The scene is a sweet repetition of sorts of Mason and Dixon’s discussion of grape people and grain people in Mason & Dixon.)

Hicks then goes through some goodbyes with April. I realized that one of my favorite bits in Shadow Ticket is that April always addresses Hicks with a different, sweet-but-pejorative nickname — “Chuckles,” “damned ox,” “Fathead,” “Einsteins” (plural), and my favorite, “ten-minute egg.” They depart in a sweet noir phantasia at Union Station.

Chapter 17 is a relatively short chapter (especially given the sprawl of Chapter 15, which, let me say, I’m sorry that I went on so long about it — part of what I’m trying to do is reread the book by writing about it and tie some themes, motifs, etc. together — I know it went on long. But it was a long chapter, chock full of Important Stuff) — sorry, Chapter 17 is a relatively short ditty, with Hicks’s train moving east through “Depression Pittsburgh, a ghost city” and then “entering deeper into the night run, having left behind and below what neon still shone, the Hoovervilles, the ghost-city light, hobo gatherings around trackside trash fires, stray auto headlights gliding briefly alongside the tracks, some fractional moonlight through the windows plus a few dim electric lamps in the observation car, deserted at this hour except for Hicks.” Reviewers and critics will rightly point out that Shadow Ticket is a detective noir; it’s possible to overlook the Gothic horror underpinnings of that genre though. Pynchon often foregrounds this Gothicism, as in the lovely description above.

Solitary in the observation car, Hicks is approached by “a Pullman porter, whose name, as he’s quick to point out, isn’t George but McKinley.” The reference here is to George Gibbs, a nineteenth century naturalist who, in the parlance of Twain, lit out for the Territory to study, among other things, indigenous languages in the Pacific Northwest.

Our Pullman porter “McKinley Gibbs turns out to be running a sideline in race records“; after riffing on politics with Hicks, he slips a few records out for our PI to peruse, including “Blind Blake, ‘Police Dog Blues.’”

We are then told that “McKinley brings it over to the club-car Victrola, puts it on. Before bar three Hicks is about to topple into a romantic nostalgia episode. ‘I’ve heard this. Not on a record, not in a club, but…'”

Presumably the referent for the “it” McKinley possesses is “Police Dog Blues” — but the “romantic nostalgia episode” reveals a different song. The vocalist? “It’s April. Natch.” We get another of Pynchon’s songs, including another of April’s nicknames for Hicks — “dimwit of my dreams” (rhymes with “strange as it seems”). But Hicks’s “romantic nostalgia episode” (American Gothic, I say) is pure reverie. He awakes — no record, no McKinley. Did either ever exist?

Chapter 18: Hicks makes it to New York and does a “courtesy drop-by at the New York branch of U-Ops, which he finds slightly west of Broadway beneath a neon sign featuring a pair of eyeballs electrically switching back and forth between bloodshot vein-crazed and lens-blank pop-bottle green.” The lurid eyeball image mixes nineteenth-century Gothicism with twentieth-century pop. Connie McSpool, on the U-Ops desk, ribs Hicks: “You just missed Judge Crater, he was in here looking for you.” Joseph Force Crater was a New York Supreme Court justice who infamously disappeared and, for a decade or two, was known as America’s “missingest” person. (Maybe surpassed, at the end of the twentieth century, by Jimmy Hoffa.) Shadow Ticket–and Pynchon’s oeuvre in general–features many characters “pulling a Crater.”

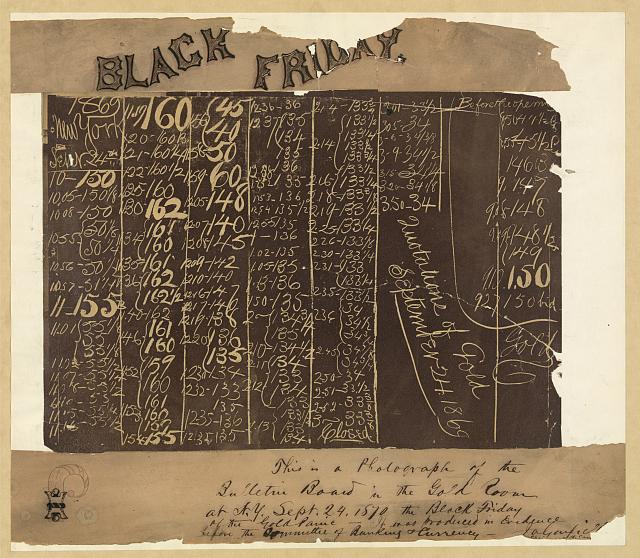

Chapter 18 concludes with Hicks overwhelmed, in true Pynchonian fashion, by a shadowy (tickety?) They. There’s “something weirdly off about Gould Fisk Fidelity and Trust,” the “bank” he finds himself at, getting an unexpected ticket to Europe and two-weeks pay. The reference here is to Black Friday, 1869, where big money boys Jay Gould and Jim Fisk tried to hijack the gold market in a Gilded Age financial thriller. Another fragment, maybe, from Against the Day.

The chapter ends with Hicks at “Club Afterbeat up in Harlem,” complaining to Connie McSpool that someone “wants me 86’d clear out of the U.S.A.”

We’ll get to that ejection soon.