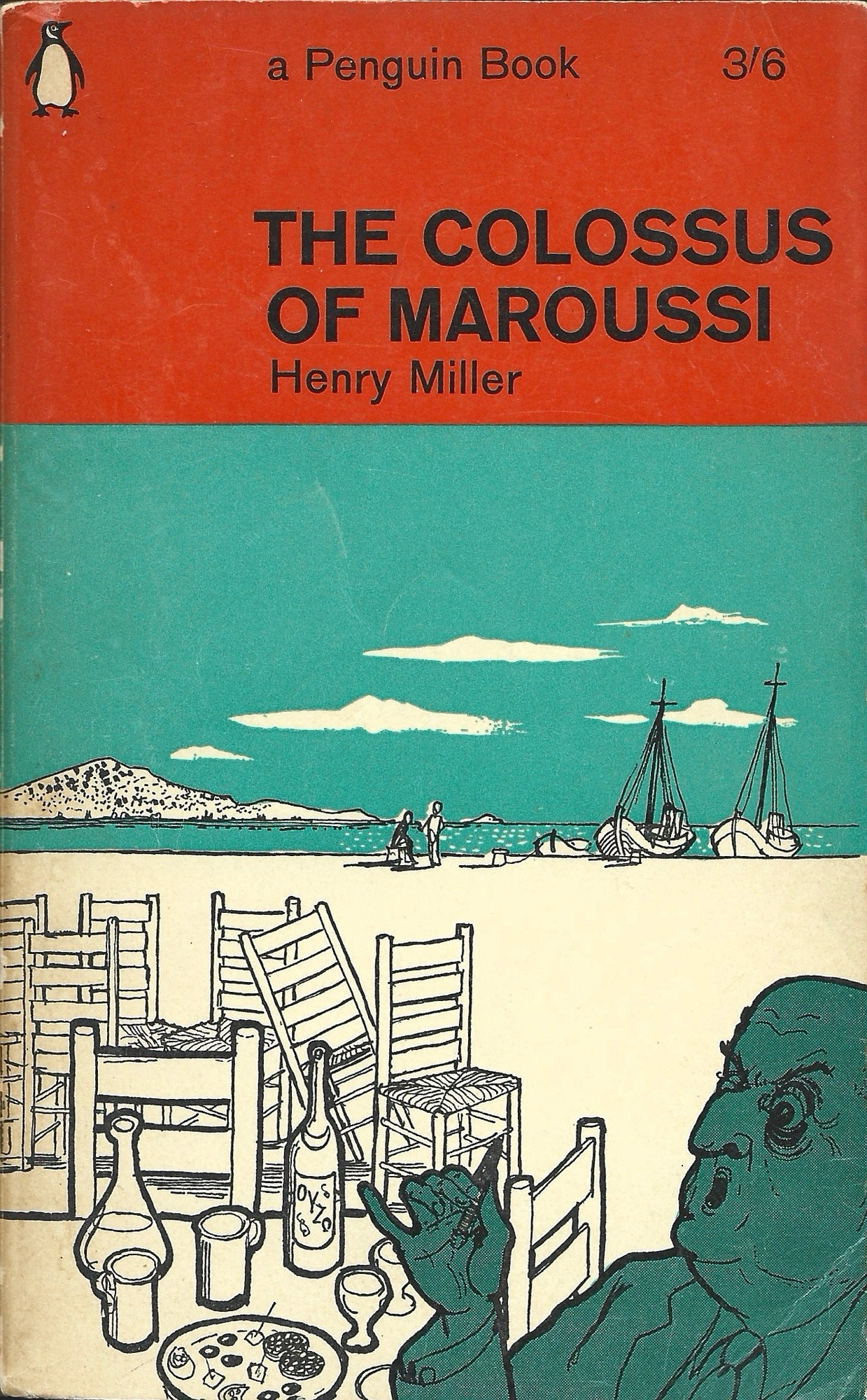

The Colossus of Maroussi, Henry Miller. Penguin Books (1964). Cover Osbert Lancaster. 248 pages.

From Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi (1941):

At Arachova Ghika got out to vomit. I stood at the edge of a deep canyon and as I looked down into its depths I saw the shadow of a great eagle wheeling over the void. We were on the very ridge of the mountains, in the midst of a convulsed land which was seemingly still writhing and twisting. The village itself had the bleak, frostbitten look of a community cut off from the outside world by an avalanche. There was the continuous roar of an icy waterfall which, though hidden from the eye, seemed omnipresent. The proximity of the eagles, their shadows mysteriously darkening the ground, added to the chill, bleak sense of desolation. And yet from Arachova to the outer precincts of Delphi the earth presents one continuously sublime, dramatic spectacle. Imagine a bubbling cauldron into which a fearless band of men descend to spread a magic carpet. Imagine this carpet to be composed of the most ingenious patterns and the most variegated hues. Imagine that men have been at this task for several thousand years and that to relax for but a season is to destroy the work of centuries. Imagine that with every groan, sneeze or hiccough which the earth vents the carpet is grievously ripped and tattered. Imagine that the tints and hues which compose this dancing carpet of earth rival in splendor and subtlety the most beautiful stained glass windows of the mediaeval cathedrals. Imagine all this and you have only a glimmering comprehension of a spectacle which is changing hourly, monthly, yearly, millennially. Finally, in a state of dazed, drunken, battered stupefaction you come upon Delphi. It is four in the afternoon, say, and a mist blowing in from the sea has turned the world completely upside down. You are in Mongolia and the faint tinkle of bells from across the gully tells you that a caravan is approaching. The sea has become a mountain lake poised high above the mountaintops where the sun is sputtering out like a rum-soaked omelette. On the fierce glacial wall where the mist lifts for a moment someone has written with lightning speed in an unknown script. To the other side, as if borne along like a cataract, a sea of grass slips over the precipitous slope of a cliff. It has the brilliance of the vernal equinox, a green which grows between the stars in the twinkling of an eye.

Seeing it in this strange twilight mist Delphi seemed even more sublime and awe-inspiring than I had imagined it to be. I actually felt relieved, upon rolling up to the little bluff above the pavilion where we left the car, to find a group of idle village boys shooting dice: it gave a human touch to the scene. From the towering windows of the pavilion, which was built along the solid, generous lines of a mediaeval fortress, I could look across the gulch and, as the mist lifted, a pocket of the sea became visible—just beyond the hidden port of Itea. As soon as we had installed our things we looked for Katsimbalis whom we found at the Apollo Hotel—I believe he was the only guest since the departure of H. G. Wells under whose name I signed my own in the register though I was not stopping at the hotel. He, Wells, had a very fine, small hand, almost womanly, like that of a very modest, unobtrusive person, but then that is so characteristic of English handwriting that there is nothing unusual about it.

By dinnertime it was raining and we decided to eat in a little restaurant by the roadside. The place was as chill as the grave. We had a scanty meal supplemented by liberal portions of wine and cognac. I enjoyed that meal immensely, perhaps because I was in the mood to talk. As so oft en happens, when one has come at last to an impressive spot, the conversation had absolutely nothing to do with the scene. I remember vaguely the expression of astonishment on Ghika’s and Katsimbalis’ faces as I unlimbered at length upon the American scene. I believe it was a description of Kansas that I was giving them; at any rate it was a picture of emptiness and monotony such as to stagger them. When we got back to the bluff behind the pavilion, whence we had to pick our way in the dark, a gale was blowing and the rain was coming down in bucketfuls. It was only a short stretch we had to traverse but it was perilous. Being somewhat lit up I had supreme confidence in my ability to find my way unaided. Now and then a flash of lightning lit up the path which was swimming in mud. In these lurid moments the scene was so harrowingly desolate that I felt as if we were enacting a scene from Macbeth. “Blow wind and crack!” I shouted, gay as a mud-lark, and at that moment I slipped to my knees and would have rolled down a gully had not Katsimbalis caught me by the arm. When I saw the spot next morning I almost fainted.