There’s a scene in Adaptation (dir. Spike Jonze, 2002), where “real life” screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (played by Nick Cage) delivers a railing lament that he can’t create the film he wants to–a film like “real life,” a film where people don’t face huge crises, where people don’t change, where nothing much happens. Adaptation unravels into a farce on Hollywood as Charlie’s twin brother Donald takes over the movie, clumsily forcing sex, drugs, and violence into a story frame that wasn’t meant to bear such themes. Perhaps last year’s Old Joy is the movie Charlie Kaufman would have wanted to make, if he could have.

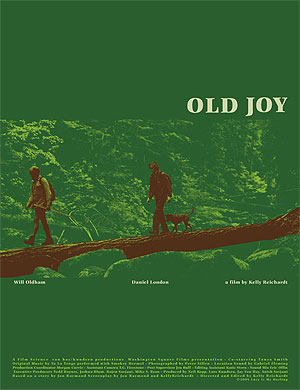

I picked up Old Joy for two simple reasons: 1) the AV Club seemed to love it and 2) Will Oldham is one of the two leads (digression: a few years ago my wife and I saw Oldham perform on the tour supporting the Superwolf record. Oldham was drunk and somewhat lascivious, prompting my wife to announce that he would “never be allowed in our house.” That cracks me up to this day for some reason).

I didn’t expect to like Old Joy nearly as much as I did. The story is very simple: two aging hipsters go on a weekend camping trip in the Oregon Cascades in search of an isolated hot spring. They get a little lost the first night, camp near the road, and get back on track the next day, finding the springs without incident. Then they go home. No crises, no conflict, no life-changing events, right? Well, not necessarily. This movie is subtle. Crisis and conflict are never stated or overt, but there is definitely tension between these two old friends.

Aspects of Mark (Daniel London) and Kurt (Will Oldham) remind me of both myself and just about all of my friends. Mark’s wife is very pregnant; faced with imminent fatherhood, he is more conventionally “responsible” than Kurt, who apparently doesn’t have a permanent job or residence. Kurt gets the pair lost the first day of the trip, and while Mark pores over a map looking for some directions, Kurt carelessly rolls and smokes a joint. The tension between the two is largely implicit, and the only time the movie’s crisis–are these two still friends?–rears its head is over a campfire scene, when, after many several beers, Kurt breaks down and admits that there’s “something” between the two of them, and that their relationship has somehow changed. Mark swears that everything is fine and the issue is more or less dropped, at least in dialog. However, that conversation lingers wistfully over the rest of the film and perhaps remains unresolved.

But dialog is not what this film is about. The real star of this film is director Kelly Reichardt’s lush footage of the verdant forests and streams of the Cascade Mountains. Paired with the more mundane shots of the countryside-as-seen-from-a-moving-car, these “nature shots” standout in their dreamy beauty. Reichardt’s pacing is lovely; he allows the camera to rest on still moments of tranquility, producing a soothing tone and mood that contrasts uneasily with the unspoken tensions between Mark and Kurt. Reichardt allows the forest’s own soundtrack of running water and singing birds to do much of the talking in this film, using Yo La Tengo’s beautiful soundtrack sparingly but to great effect. And at just 76 minutes, the film is a perfect length–the shots are profound at times, but never ponderous.

The overall experience of Old Joy is a mix of ineffable loss and stunning but calming beauty, perhaps best expressed in a line from Kurt. “Sorrow is just worn out joy,” he tells Mark, relating a dream he recently had. And it’s that kind of paradox that informs the film–that merging of beauty and loss and beginnings and endings. In the end, we don’t get answers, and if the characters change, those changes are understated and incremental. In Charlie Kaufman’s terms, this is a film about “real life,” and no doubt many viewers will see aspects of themselves haunting the screen.