Philip K. Dick’s bizarrely titled Galactic Pot-Healer begins in a dystopian future (more 1984 than Brave New World), before moving into–you guessed it–more galactic territory. Joe Fernwright “heals” ceramic pots–a relatively useless job, seeing as all the broken pots have now been mended. He wiles away his time playing word games with other cubicle minions across the globe, until an alien called Glimmung wisps him away to Sirius Five so that he can aid in resurrecting an ancient cathedral from the depths of an ocean where the laws of time do not apply. Lots of very strange stuff happens.

Galactic Pot-Healer is typical PKD, which is to say thoroughly atypical sci-fi with a philosophically paranoid twist (or is that a paranoid philosophical twist?). The story begins as a satire of modern workaday existence, and Dick’s assessment of cubicle life, written in the late 1960s, is almost too-prescient. Fernwright is a typical Dickian hero, a Walter Mitty figure who, real or not, gets to live his dream out (there’s a girl, of course, a sexy alien). After the action moves to Sirius Five, Dick becomes overtly concerned with the major themes of the novel. A precognitive alien race called the Kalends publish a book, a sort of daily newspaper, that accurately predicts the future. The Kalends predict that the raising of the cathedral will fail, and all involved will die. Glimmung, who is repeatedly compared to Faust by everyone in the book (all of these aliens from different planets are not only familiar with Goethe’s version, but other versions as well), attempts to prove that he is master of his own fate. Attracted to this, Fernwright risks his life in the project, and finds a new hope and vitality in meaningful work that he didn’t have back in his cubicle on Terra.

Galactic Pot-Healer is as weird as its title, and at times suffers from Dick’s manic jumpiness. One imagines him sweating out the novel over a few weeks, feverishly hacking at his typewriter. The links between concrete events–narrative action–are often frantic (if they exist at all), and there’s little subtlety here: Dick’s characters will quote verbatim Kant or Goethe, or wax heavy on determinism and ontology at the drop of a hat. At other times, the prose sings with lyrical beauty, sorrow, and a density of imagination that more than makes up for Dick’s occasional lack of cohesion. As good a place as any to begin a journey into the weird wonderful world of PKD.

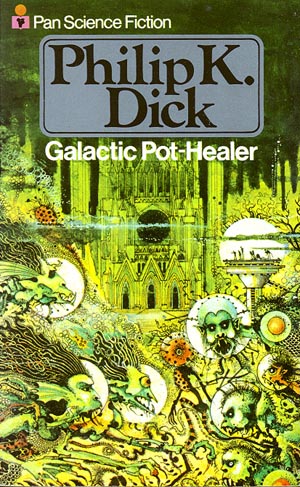

(Images from philipkdick.com’s kickass covers gallery)

why do people never mention the completely unsatisfying end? That is the main reason I recommend you NEVER EVER read this book.

LikeLike

Maybe people “never mention the completely unsatisfying end” because they found the end satisfying. If I recall correctly, the book ends with the protagonist actually creating pots instead of just repairing them.

LikeLike