Compared to many forms that lend themselves to art or craft—drama, the novel, painting, the composition of music, even the interpretation of music, like, oh, say, singing the national anthem before the game, infinite other forms that seem to thrive, almost to wallow, in permutation, assuming new content, a mother lode of fresh ideas and differentiated styles as they’re taken up by one artist after another—it’s extraordinary how furniture is like most other furniture, as if furniture, alone among crafts, not only lived along the perimeters of some platonic ideal but had somehow actually managed to colonize it: an imperialism of the conventional. Except for a detail here, a detail there, inlay, marquetry, the pile-on of money, of pharaohs’ or aristocracy’s royal dispensations, a couch is a couch, an escritoire an escritoire. Beds resemble beds, tables and chairs are like tables and chairs. In domestic arrangements, form, bound to the custom cloth of human shape, really does follow function. The height of a table has to do with average lap tolerances. Chairs and beds are the hard aura of a strictly skeletal repose. Even so, something’s busted, I think, in the imagination of the furniture designers—I except the art directors of certain major motion pictures set in Manhattan apartments; talkin’ environment, the ecology of “life-style,” of plot and character, what the principals look like against the bookcase, propped among the furnishings; one must learn the script of one’s life and be able to afford it; because only in movies does furniture play well—all lamps and appointments, all cunning, edge-of-the-field doodad and inspired house-dower; one has at least the illusion one could live with this stuff, that it won’t vanish in a season like a Nehru shirt—something stuck in the vision, some sorcerer’s-apprentice effect, which permits to keep on coming and keep on coming with minimal variation, if any, what has come before. It isn’t anything elegant as highest math happening here, just lump-sum arrangement, ball-park figure, bottom line. It’s the fallacy of the assembly line, the notion that only costs get cut in such a wide sweep of swath. No, but really. Isn’t it astonishing that personality, surely as real as the width of one’s shoulders or the breadth of one’s beam, should be so infinite but attention to body so meager and hand-to-mouth that—chairs, say chairs, I know about chairs—there’s been less progress in the design of chairs than in the design of luggage. (I speak as a cripple full-fledged—chairs are a hangup with me—but set that aside.) It’s as if clothing came in a single size, pants like tube socks, every dress like a muumuu. And a rule of the chair seems to be that if it’s beautiful it’s rarely comfortable, if comfortable it rarely makes the cut to beauty.

Indeed, there are so few contemporary “museum-quality” chairs one can almost list them—Marcel Breuer’s side chairs, his “Wassily” chair like a leather-and-steel cat’s cradle; Jacobsen’s “Egg” chair; Thonet’s bentwood rockers; Mies Van Der Rohe’s “Barcelona”; Saarinen’s molded plastic chairs on their round bases and tapered stems like cross sections of parfaits; all Eames’s ubiquitous plastic like stackable poker chips or the pounded, hollowed-out centers of catchers’ mitts, and as locked into a vision of the fifties as pole lamps, his famous lounge chair and ottoman that, like the Nehru shirt, have become a cliché. A spectrum of vernacular chairs—soda-fountain chairs, directors’ chairs, black canvas camp chairs, those crushed—almost imploded—white or charcoal leather pillow chairs like soft fortresses or marshmallow thrones; some of the new ergonomic chairs that sit on you as much as you ever manage to sit on them.

So I know about chairs and still have my eye out, never mind I’m sixty if I’m a day, for that evasive, lost-chord masterpiece of the genre, which, like love, I’ll know when I see like a sort of fate.

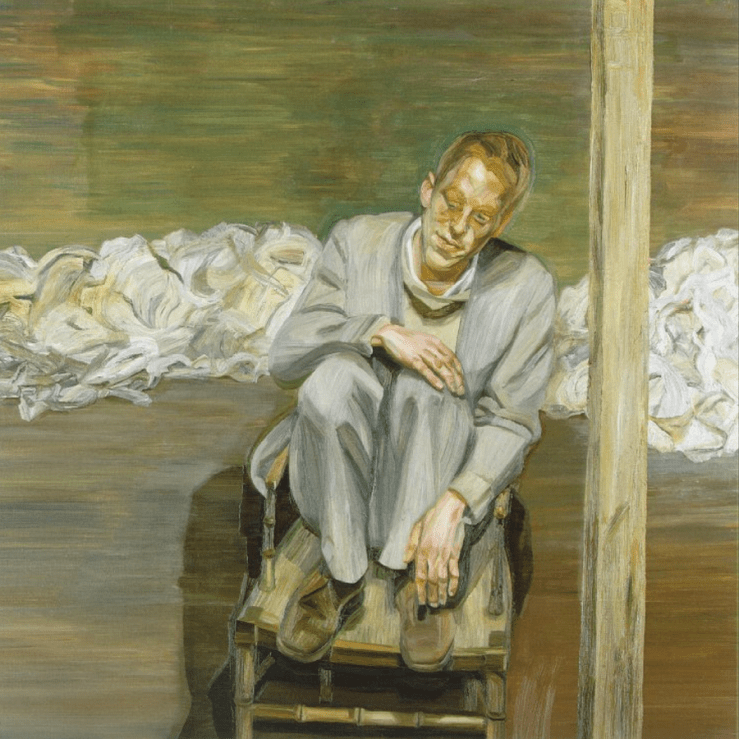

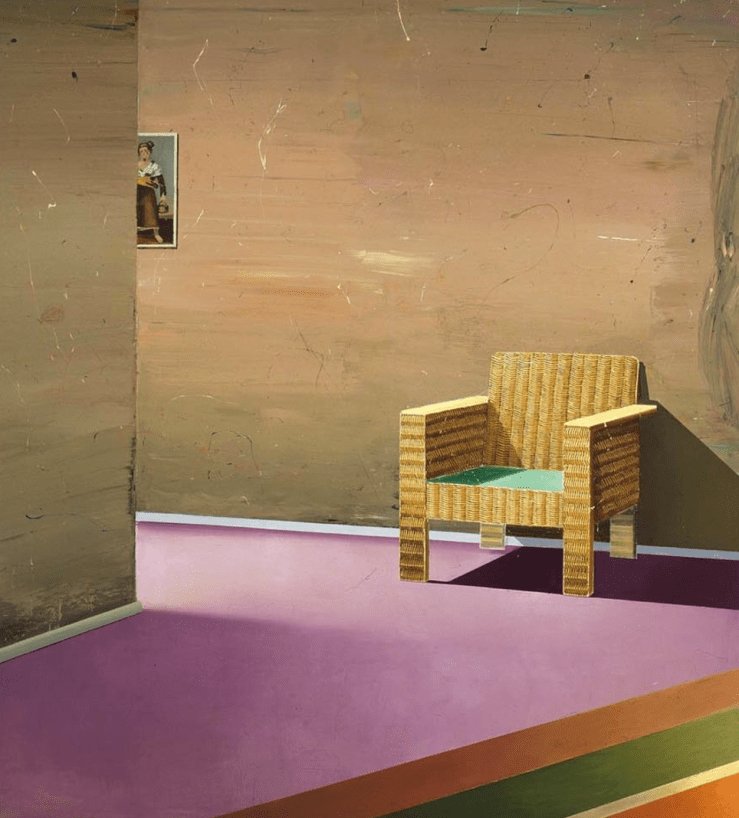

Though maybe not. Not because I haven’t the imagination to cut my losses, or even the courage to finesse my life and choose to sit out the close of my days in desuetudinous splendor, but because it may not exist. The chair, my gorgeous prosthetic of choice, may not have been fashioned yet. Because oddly, strangely, ultimately, chairs are all attitude, molds of the supine or up on pointe, aggressive or submissive as sexual position. Occupied or unoccupied either, they are shadows, ghosts, signs of the been-and-gone, some pipe-and-slippers choreography of spiritual disposition, how one chooses to acquit oneself, highly personalized as an arrangement of flowers, and oh, oh, if one but had the body for it one would live out one’s days in Van Gogh’s room at Arles, eating up comfort and beauty and having it, too, there in one last fell binge of boyhood in the cane and wood along those powder-blue walls of the utile, of basin and pitcher, of military brush and drinking glass, of apothecary bottles clear as gin on a crowded corner of the nightstand, to be there on the feather bed, on the oilcloth-looking floor amid one’s things. All, as I say, you have to know is the script of your life.

From Stanley Elkin’s 1991 essay “Some Overrated Masterpieces.” Collected in Pieces of Soap.