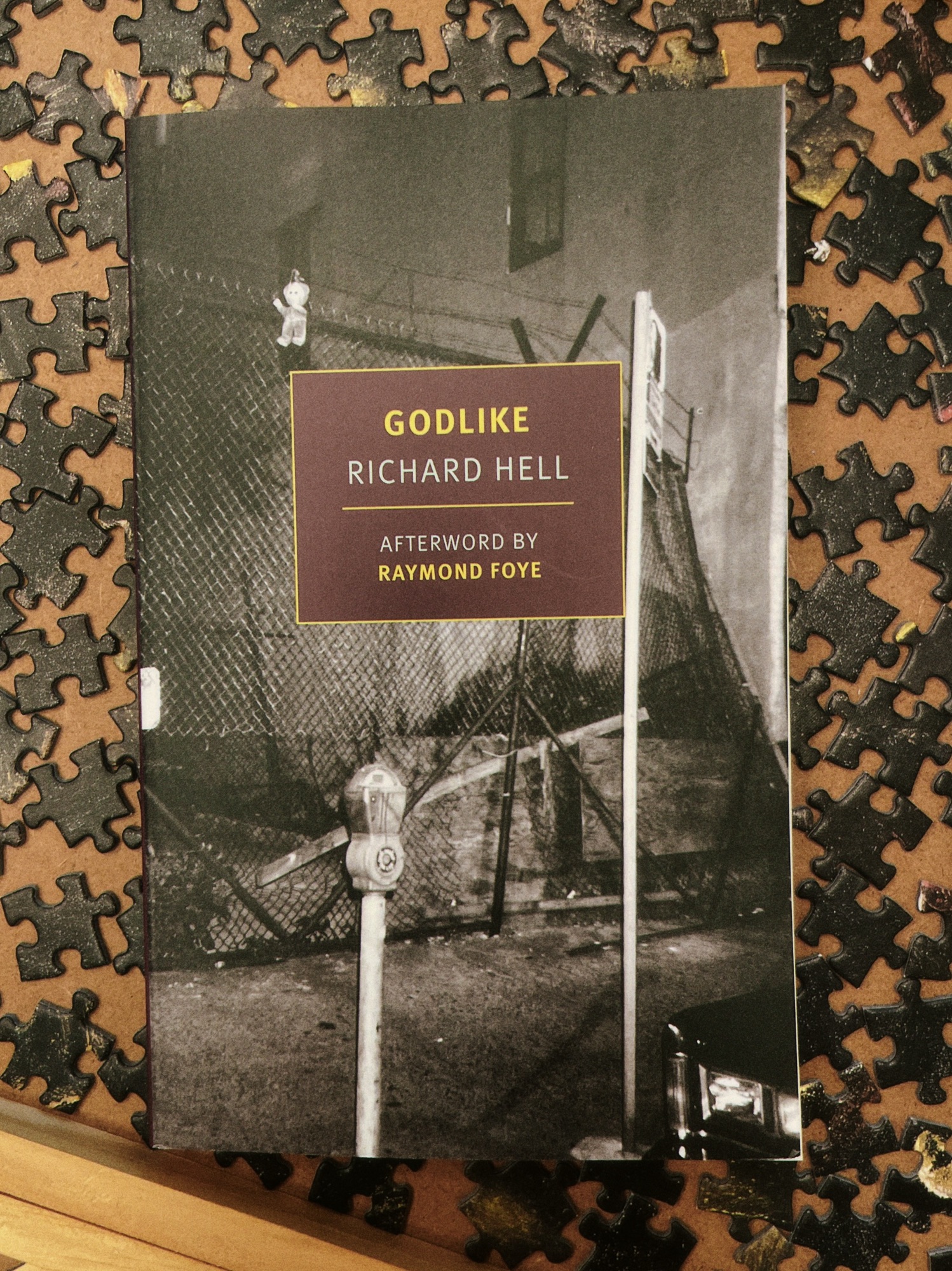

Richard Hell’s 2005 novel Godlike is getting a new printing from NYRB. Godlike reimagines the volatile Verlaine–Rimbaud dyad as a 1970s No Wave New York collision of art, desire, and language language language. Symbolist rebellion transmutes into downtown punk nihilism, drugs, and poetry. This corrosive Künstlerroman was originally issued by Dennis Cooper’s Little House on the Bowery (an imprint of Akashic books). Read the description/blurb at NYRB; here’s a taste from Chapter 15, around the middle of the novel:

They spent the greatest amount of their time together reading and writing and sometimes talking in T’s apartment. These were probably their best times too despite being experienced largely as tedium. They preferred the times of thrills, but the thrills grew out of the tension; and the mild, mildly restless, half-frustrated times of the many nights and late afternoons of doing almost nothing in T’s apartment, or walking the streets without direction, were their true lives.

T’s room was like some kind of glum office in its lack of daylight and its featurelessness, but with the little pictures now tacked on the walls, and the typewriter and sheets of paper, and the drugs, it got some character. He’d picked up a few stray pieces of furniture on the streets, including a table and three chairs, crates for shelves, and a beat-up old oriental rug. There was a secondhand portable record player too and a few albums.

They drank coffee and beer and sometimes codeine cough syrup and sometimes smoked some grass or snorted a little THC or mescaline and every once in a while a tiny bit of heroin, but mostly they lay around and lazily, impatiently goofed and wrote and complained, goading each other. Sometimes in the middle of the night one of them would go out for a container of fresh ice cream from Gem’s Spa. They’d go to a movie sometimes, or wander the rows of used bookstores on Fourth Avenue, or drink in a bar, but most of t he time was spent in the dim back apartment.

The days and nights were as endless as wallpaper patterns. Boredom and irritation were normal and lengthened out into sometimes-mean giggles and into pages of writing. Writing was their pay. Books were reality. The room was a cruder dimension-poor annex to the pages of writing. The writing, as casual as it was—smeared eraseable typing-pages with revisions scribbled on and crumpled pages of rejected tries—was the brightly lit and wildly littered universe erupting out from the dark, poor, inexpressive room.

How odd is it to have as a purpose in life the aim of treating life-in the medium created for the purpose of coldly corresponding to it, words—as raw material for amusing variations on itself? Sometimes T. and Paul fantasized about this, imagining themselves as godlike philosopher poets encouched in the advanced civilization, languorously sipping their fermented grain as they spun ideas and mental-sensual constructions of life-language in the air for the pleasure of their own delectation.