Imitators of original authors might be compared to plaster casts of marble statues, or the imitative book to a cast of the original marble.

For a child’s story,–the voyage of a little boat made of a chip, with a birch-bark sail, down a river.

Fourier states that, in the progress of the world, the ocean is to lose its saltness, and acquire the taste of a peculiarly flavored lemonade.

How pleasant it is to see a human countenance which cannot be insincere,–in reference to baby’s smile.

The best of us being unfit to die, what an inexpressible absurdity to put the worst to death!

“Is that a burden of sunshine on Apollo’s back?” asked one of the children,–of the chlamys on our Apollo Belvedere.

Tag: Note-Books

An article on cemeteries, and other ideas from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books

The spells of witches have the power of producing meats and viands that have the appearance of a sumptuous feast, which the Devil furnishes: But a Divine Providence seldom permits the meat to be good, but it has generally some bad taste or smell,–mostly wants salt,–and the feast is often without bread.

An article on cemeteries, with fantastic ideas of monuments; for instance, a sundial;–a large, wide carved stone chair, with some such motto as “Rest and Think,” and others, facetious or serious.

“Mamma, I see a part of your smile,”–a child to her mother, whose mouth was partly covered by her hand.

“The syrup of my bosom,”–an improvisation of a little girl, addressed to an imaginary child.

“The wind-turn,” “the lightning-catch,” a child’s phrases for weathercock and lightning-rod.

“Where’s the man-mountain of these Liliputs?” cried a little boy, as he looked at a small engraving of the Greeks getting into the wooden horse.

When the sun shines brightly on the new snow, we discover ranges of hills, miles away towards the south, which we have never seen before.

To have the North Pole for a fishing-pole, and the Equinoctial Line for a fishing-line.

This is Thanksgiving Day, a good old festival | Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Journal Entry for November 24, 1843

Thursday, November 24th.–This is Thanksgiving Day, a good old festival, and we have kept it with our hearts, and, besides, have made good cheer upon our turkey and pudding, and pies and custards, although none sat at our board but our two selves. There was a new and livelier sense, I think, that we have at last found a home, and that a new family has been gathered since the last Thanksgiving Day. There have been many bright, cold days latterly,–so cold that it has required a pretty rapid pace to keep one’s self warm a-walking. Day before yesterday I saw a party of boys skating on a pond of water that has overflowed a neighboring meadow. Running water has not yet frozen. Vegetation has quite come to a stand, except in a few sheltered spots. In a deep ditch we found a tall plant of the freshest and healthiest green, which looked as if it must have grown within the last few weeks. We wander among the wood-paths, which are very pleasant in the sunshine of the afternoons, the trees looking rich and warm,–such of them, I mean, as have retained their russet leaves; and where the leaves are strewn along the paths, or heaped plentifully in some hollow of the hills, the effect is not without a charm. To-day the morning rose with rain, which has since changed to snow and sleet; and now the landscape is as dreary as can well be imagined,–white, with the brownness of the soil and withered grass everywhere peeping out. The swollen river, of a leaden hue, drags itself sullenly along; and this may be termed the first winter’s day.

“A very fanciful person, when dead, to have his burial in a cloud” (And other ideas from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books)

- When scattered clouds are resting on the bosoms of hills, it seems as if one might climb into the heavenly region, earth being so intermixed with sky, and gradually transformed into it.

- A stranger, dying, is buried; and after many years two strangers come in search of his grave, and open it.

- The strange sensation of a person who feels himself an object of deep interest, and close observation, and various construction of all his actions, by another person.

- Letters in the shape of figures of men, etc. At a distance, the words composed by the letters are alone distinguishable. Close at hand, the figures alone are seen, and not distinguished as letters. Thus things may have a positive, a relative, and a composite meaning, according to the point of view.

- “Passing along the street, all muddy with puddles, and suddenly seeing the sky reflected in these puddles in such a way as quite to conceal the foulness of the street.”

- A young man in search of happiness,–to be personified by a figure whom he expects to meet in a crowd, and is to be recognized by certain signs. All these signs are given by a figure in various garbs and actions, but he does not recognize that this is the sought-for person till too late.

- If cities were built by the sound of music, then some edifices would appear to be constructed by grave, solemn tones,–others to have danced forth to light, fantastic airs.

- Familiar spirits, according to Lilly, used to be worn in rings, watches, sword-hilts. Thumb-rings were set with jewels of extraordinary size.

- A very fanciful person, when dead, to have his burial in a cloud.

Nine Figments from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Notebook

- An ancient wineglass (Miss Ingersol’s), long-stalked, with a small, cup-like bowl, round which is wreathed a branch of grape-vine, with a rich cluster of grapes, and leaves spread out. There is also some kind of a bird flying. The whole is excellently cut or engraved.

- In the Duke of Buckingham’s comedy, “The Chances,” Don Frederic says of Don John (they are two noble Spanish gentlemen), “One bed contains us ever.”

- A person, while awake and in the business of life, to think highly of another, and place perfect confidence in him, but to be troubled with dreams in which this seeming friend appears to act the part of a most deadly enemy. Finally it is discovered that the dream-character is the true one. The explanation would be–the soul’s instinctive perception.

- Pandora’s box for a child’s story.

- Moonlight is sculpture; sunlight is painting.

- “A person to look back on a long life ill-spent, and to picture forth a beautiful life which he would live, if he could be permitted to begin his life over again. Finally to discover that he had only been dreaming of old age,–that he was really young, and could live such a life as he had pictured.”

- A newspaper, purporting to be published in a family, and satirizing the political and general world by advertisements, remarks on domestic affairs,–advertisement of a lady’s lost thimble, etc.

- L. H—-. She was unwilling to die, because she had no friends to meet her in the other world. Her little son F. being very ill, on his recovery she confessed a feeling of disappointment, having supposed that he would have gone before, and welcomed her into heaven!

- H. L. C—- heard from a French Canadian a story of a young couple in Acadie. On their marriage day, all the men of the Province were summoned to assemble in the church to hear a proclamation. When assembled, they were all seized and shipped off to be distributed through New England,–among them the new bridegroom. His bride set off in search of him,–wandered about New England all her lifetime, and at last, when she was old, she found her bridegroom on his death-bed. The shock was so great that it killed her likewise.

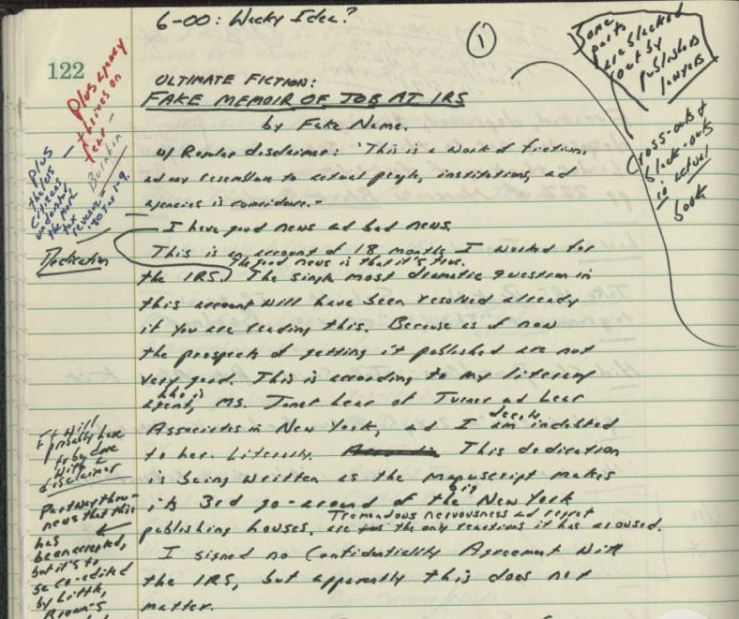

Ultimate Fiction: Fake Memoir of Job at IRS by Fake Name (David Foster Wallace Archive)

The David Foster Wallace archive at the Harry Ransom Center UT has made some documents from The Pale King accessible online, including a few pages of his workbook, handwritten drafts, and typed edits.

The David Foster Wallace archive at the Harry Ransom Center UT has made some documents from The Pale King accessible online, including a few pages of his workbook, handwritten drafts, and typed edits.

(Via).

Five Story Ideas from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books

- All the dead that had ever been drowned in a certain lake to arise.

- Character of a man who, in himself and his external circumstances, shall be equally and totally false: his fortune resting on baseless credit,–his patriotism assumed,–his domestic affections, his honor and honesty, all a sham. His own misery in the midst of it,–it making the whole universe, heaven and earth alike, an unsubstantial mockery to him.

- Dr. Johnson’s penance in Uttoxeter Market. A man who does penance in what might appear to lookers-on the most glorious and triumphal circumstance of his life. Each circumstance of the career of an apparently successful man to be a penance and torture to him on account of some fundamental error in early life.

- A person to catch fire-flies, and try to kindle his household fire with them. It would be symbolical of something.

- Thanksgiving at the Worcester Lunatic Asylum. A ball and dance of the inmates in the evening,–a furious lunatic dancing with the principal’s wife. Thanksgiving in an almshouse might make a better sketch.

I had a fantasy of heaven’s being broken into fleecy fragments | Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Notebook Entry for August 27, 1839

August 27th.–I have been stationed all day at the end of Long Wharf, and I rather think that I had the most eligible situation of anybody in Boston. I was aware that it must be intensely hot in the midst of the city; but there was only a short space of uncomfortable heat in my region, half-way towards the centre of the harbor; and almost all the time there was a pure and delightful breeze, fluttering and palpitating, sometimes shyly kissing my brow, then dying away, and then rushing upon me in livelier sport, so that I was fain to settle my straw hat more tightly upon my head. Late in the afternoon, there was a sunny shower, which came down so like a benediction that it seemed ungrateful to take shelter in the cabin or to put up an umbrella. Then there was a rainbow, or a large segment of one, so exceedingly brilliant and of such long endurance that I almost fancied it was stained into the sky, and would continue there permanently. And there were clouds floating all about,–great clouds and small, of all glorious and lovely hues (save that imperial crimson which was revealed to our united gaze),–so glorious, indeed, and so lovely, that I had a fantasy of heaven’s being broken into fleecy fragments and dispersed through space, with its blest inhabitants dwelling blissfully upon those scattered islands.

Nathaniel Hawthorne Runs Into Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller in Sleepy Hollow (Note-Book Entry for August 22nd, 1842)

Monday, August 22d.—

I took a walk through the woods yesterday afternoon, to Mr. Emerson’s, with a book which Margaret Fuller had left, after a call on Saturday eve. I missed the nearest way, and wandered into a very secluded portion of the forest; for forest it might justly be called, so dense and sombre was the shade of oaks and pines. Once I wandered into a tract so overgrown with bushes and underbrush that I could scarcely force a passage through. Nothing is more annoying than a walk of this kind, where one is tormented by an innumerable host of petty impediments. It incenses and depresses me at the same time. Always when I flounder into the midst of bushes, which cross and intertwine themselves about my legs, and brush my face, and seize hold of my clothes, with their multitudinous grip,–always, in such a difficulty, I feel as if it were almost as well to lie down and die in rage and despair as to go one step farther. It is laughable, after I have got out of the moil, to think how miserably it affected me for the moment; but I had better learn patience betimes, for there are many such bushy tracts in this vicinity, on the margins of meadows, and my walks will often lead me into them. Escaping from the bushes, I soon came to an open space among the woods,–a very lovely spot, with the tall old trees standing around as quietly as if no one had intruded there throughout the whole summer. A company of crows were holding their Sabbath on their summits. Apparently they felt themselves injured or insulted by my presence; for, with one consent, they began to Caw! caw! caw! and, launching themselves sullenly on the air, took flight to some securer solitude. Mine, probably, was the first human shape that they had seen all day long,–at least, if they had been stationary in that spot; but perhaps they had winged their way over miles and miles of country, had breakfasted on the summit of Graylock, and dined at the base of Wachusett, and were merely come to sup and sleep among the quiet woods of Concord. But it was my impression at the time, that they had sat still and silent on the tops of the trees all through the Sabbath day, and I felt like one who should unawares disturb an assembly of worshippers. A crow, however, has no real pretensions to religion, in spite of his gravity of mien and black attire. Crows are certainly thieves, and probably infidels. Nevertheless, their voices yesterday were in admirable accordance with the influences of the quiet, sunny, warm, yet autumnal afternoon. They were so far above my head that their loud clamor added to the quiet of the scene, instead of disturbing it. There was no other sound, except the song of the cricket, which is but an audible stillness; for, though it be very loud and heard afar, yet the mind does not take note of it as a sound, so entirely does it mingle and lose its individuality among the other characteristics of coming autumn. Alas for the summer! The grass is still verdant on the hills and in the valleys; the foliage of the trees is as dense as ever, and as green; the flowers are abundant along the margin of the river, and in the hedge-rows, and deep among the woods; the days, too, are as fervid as they were a month ago; and yet in every breath of wind and in every beam of sunshine there is an autumnal influence. I know not how to describe it. Methinks there is a sort of coolness amid all the heat, and a mildness in the brightest of the sunshine. A breeze cannot stir without thrilling me with the breath of autumn, and I behold its pensive glory in the far, golden gleams among the long shadows of the trees. The flowers, even the brightest of them,–the golden-rod and the gorgeous cardinals,–the most glorious flowers of the year,–have this gentle sadness amid their pomp. Pensive autumn is expressed in the glow of every one of them. I have felt this influence earlier in some years than in others. Sometimes autumn may be perceived even in the early days of July. There is no other feeling like that caused by this faint, doubtful, yet real perception, or rather prophecy, of the year’s decay, so deliciously sweet and sad at the same time.

“Titles for Unwritten Articles, Essays, and Stories” — Samuel Butler

“Titles for Unwritten Articles, Essays, and Stories”

from Samuel Butler’s Note-Books

- The Art of Quarrelling.

- Christian Death-beds.

- The Book of Babes and Sucklings.

- Literary Struldbrugs.

- The Life of the World to Come.

- The Limits of Good Faith.

- Art, Money and Religion.

- The Third Class Excursion Train, or Steam-boat, as the Church of the Future.

- The Utter Speculation involved in much of the good advice that is commonly given—as never to sell a reversion, etc.

- Tracts for Children, warning them against the virtues of their elders.

- Making Ready for Death as a Means of Prolonging Life. An Essay concerning Human Misunderstanding. So McCulloch [a fellow art-student at Heatherley’s, a very fine draughtsman] used to say that he drew a great many lines and saved the best of them. Illusion, mistake, action taken in the dark—these are among the main sources of our progress.

- The Elements of Immorality for the Use of Earnest Schoolmasters.

- Family Prayers: A series of perfectly plain and sensible ones asking for what people really do want without any kind of humbug.

- A Penitential Psalm as David would have written it if he had been reading Herbert Spencer.

- A Few Little Crows which I have to pick with various people.

- The Scylla of Atheism and the Charybdis of Christianity.

- The Battle of the Prigs and Blackguards.

- That Good may Come.

- The Marriage of Inconvenience.

- The Judicious Separation.

- Fooling Around.

- Higgledy-Piggledy.

- The Diseases and Ordinary Causes of Mortality among Friendships.

- The finding a lot of old photographs at Herculaneum or Thebes; and they should turn out to be of no interest.

- On the points of resemblance and difference between the dropping off of leaves from a tree and the dropping off of guests from a dinner or a concert.

- The Sense of Touch: An essay showing that all the senses resolve themselves ultimately into a sense of touch, and that eating is touch carried to the bitter end. So there is but one sense—touch—and the amœba has it. When I look upon the foraminifera I look upon myself.

- The China Shepherdess with Lamb on public-house chimney-pieces in England as against the Virgin with Child in Italy.

- For a Medical pamphlet: Cant as a means of Prolonging Life.

- For an Art book: The Complete Pot-boiler; or what to paint and how to paint it, with illustrations reproduced from contemporary exhibitions and explanatory notes.

- For a Picture: St. Francis preaching to Silenus. Fra Angelico and Rubens might collaborate to produce this picture.

- The Happy Mistress. Fifteen mistresses apply for three cooks and the mistress who thought herself nobody is chosen by the beautiful and accomplished cook.

- The Complete Drunkard. He would not give money to sober people, he said they would only eat it and send their children to school with it.

- The Contented Porpoise. It knew it was to be stuffed and set up in a glass case after death, and looked forward to this as to a life of endless happiness.

- The Flying Balance. The ghost of an old cashier haunts a ledger, so that the books always refuse to balance by the sum of, say, £1.15.11. No matter how many accountants are called in, year after year the same error always turns up; sometimes they think they have it right and it turns out there was a mistake, so the old error reappears. At last a son and heir is born, and at some festivities the old cashier’s name is mentioned with honour. This lays his ghost. Next morning the books are found correct and remain so.

- A Dialogue between Isaac and Ishmael on the night that Isaac came down from the mountain with his father. The rebellious Ishmael tries to stir up Isaac, and that good young man explains the righteousness of the transaction—without much effect.

- Bad Habits: on the dropping them gradually, as one leaves off requiring them, on the evolution principle.

- A Story about a Freethinking Father who has an illegitimate son which he considers the proper thing; he finds this son taking to immoral ways, e.g. he turns Christian, becomes a clergyman and insists on marrying.

- For a Ballad: Two sets of rooms in some alms-houses at Cobham near Gravesend have an inscription stating that they belong to “the Hundred of Hoo in the Isle of Grain.” These words would make a lovely refrain for a ballad.

- A story about a man who suffered from atrophy of the purse, or atrophy of the opinions; but whatever the disease some plausible Latin, or imitation-Latin name must be found for it and also some cure.

- A Fairy Story modelled on the Ugly Duckling of Hans Andersen about a bumptious boy whom all the nice boys hated. He finds out that he was really at last caressed by the Huxleys and Tyndalls as one of themselves.

- A Collection of the letters of people who have committed suicide; and also of people who only threaten to do so. The first may be got abundantly from reports of coroners’ inquests, the second would be harder to come by.

- The Structure and Comparative Anatomy of Fads, Fancies and Theories; showing, moreover, that men and women exist only as the organs and tools of the ideas that dominate them; it is the fad that is alone living.

- An Astronomical Speculation: Each fixed star has a separate god whose body is his own particular solar system, and these gods know each other, move about among each other as we do, laugh at each other and criticise one another’s work. Write some of their discourses with and about one another.

Continue reading ““Titles for Unwritten Articles, Essays, and Stories” — Samuel Butler”

Four Notes from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books

- Punishment of a miser,–to pay the drafts of his heir in his tomb.

- A series of strange, mysterious, dreadful events to occur, wholly destructive of a person’s happiness. He to impute them to various persons and causes, but ultimately finds that he is himself the sole agent. Moral, that our welfare depends on ourselves.

- The strange incident in the court of Charles IX. of France: he and five other maskers being attired in coats of linen covered with pitch and bestuck with flax to represent hairy savages. They entered the hall dancing, the five being fastened together, and the king in front. By accident the five were set on fire with a torch. Two were burned to death on the spot, two afterwards died; one fled to the buttery, and jumped into a vessel of water. It might be represented as the fate of a squad of dissolute men.

- A perception, for a moment, of one’s eventual and moral self, as if it were another person,–the observant faculty being separated, and looking intently at the qualities of the character. There is a surprise when this happens,–this getting out of one’s self,–and then the observer sees how queer a fellow he is.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

July 13, 1838 (Nathaniel Hawthorne)

July 13th.–A show of wax-figures, consisting almost wholly of murderers and their victims,–Gibbs and Hansley, the pirates, and the Dutch girl whom Gibbs murdered. Gibbs and Hansley were admirably done, as natural as life; and many people who had known Gibbs would not, according to the showman, be convinced that this wax-figure was not his skin stuffed. The two pirates were represented with halters round their necks, just ready to be turned off; and the sheriff stood behind them, with his watch, waiting for the moment. The clothes, halter, and Gibbs’s hair were authentic. E. K. Avery and Cornell,–the former a figure in black, leaning on the back of a chair, in the attitude of a clergyman about to pray; an ugly devil, said to be a good likeness. Ellen Jewett and R. P. Robinson, she dressed richly, in extreme fashion, and very pretty; he awkward and stiff, it being difficult to stuff a figure to look like a gentleman. The showman seemed very proud of Ellen Jewett, and spoke of her somewhat as if this wax-figure were a real creation. Strong and Mrs. Whipple, who together murdered the husband of the latter. Lastly the Siamese twins. The showman is careful to call his exhibition the “Statuary.” He walks to and fro before the figures, talking of the history of the persons, the moral lessons to be drawn therefrom, and especially of the excellence of the wax-work. He has for sale printed histories of the personages. He is a friendly, easy-mannered sort of a half-genteel character, whose talk has been moulded by the persons who most frequent such a show; an air of superiority of information, a moral instructor, with a great deal of real knowledge of the world. He invites his departing guests to call again and bring their friends, desiring to know whether they are pleased; telling that he had a thousand people on the 4th of July, and that they were all perfectly satisfied. He talks with the female visitors, remarking on Ellen Jewett’s person and dress to them, he having “spared no expense in dressing her; and all the ladies say that a dress never set better, and he thinks he never knew a handsomer female.” He goes to and fro, snuffing the candles, and now and then holding one to the face of a favorite figure. Ever and anon, hearing steps upon the staircase, he goes to admit a new visitor. The visitors,–a half-bumpkin, half country-squire-like man, who has something of a knowing air, and yet looks and listens with a good deal of simplicity and faith, smiling between whiles; a mechanic of the town; several decent-looking girls and women, who eye Ellen herself with more interest than the other figures,–women having much curiosity about such ladies; a gentlemanly sort of person, who looks somewhat ashamed of himself for being there, and glances at me knowingly, as if to intimate that he was conscious of being out of place; a boy or two, and myself, who examine wax faces and faces of flesh with equal interest. A political or other satire might be made by describing a show of wax-figures of the prominent public men; and by the remarks of the showman and the spectators, their characters and public standing might be expressed. And the incident of Judge Tyler as related by E—- might be introduced

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

“Viciousness is a bag with which man is born” (From Chekhov’s Note-Books)

* * * * *

Viciousness is a bag with which man is born.

* * * * *

A lady looking like a fish standing on its head; her mouth like a slit, one longs to put a penny in it.

* * * * *

Russians abroad: the men love Russia passionately, but the women don’t like her and soon forget her.

* * * * *

Chemist Propter.

* * * * *

Rosalie Ossipovna Aromat.

* * * * *

It is easier to ask of the poor than of the rich.

* * * * *

And she began to engage in prostitution, got used to sleeping on the bed, while her aunt, fallen into poverty, used to lie on the little carpet by her side and jumped up each time the bell rang; when they left, she would say mindingly, with a pathetic grimace; “Something for the chamber-maid.” And they would tip her sixpence.

* * * * *

Prostitutes in Monte Carlo, the whole tone is prostitutional; the palm trees, it seems, are prostitutes, and the chickens are prostitutes.

* * * * *

June 16, 1838 (Nathaniel Hawthorne)

Tremont, Boston, June 16th.–Tremendously hot weather to-day. Went on board the Cyane to see Bridge, the purser. Took boat from the end of Long Wharf, with two boatmen who had just landed a man. Row round to the starboard side of the sloop, where we pass up the steps, and are received by Bridge, who introduces us to one of the lieutenants,–Hazard. Sailors and midshipmen scattered about,–the middies having a foul anchor, that is, an anchor with a cable twisted round it, embroidered on the collars of their jackets. The officers generally wear blue jackets, with lace on the shoulders, white pantaloons, and cloth caps. Introduced into the cabin,–a handsome room, finished with mahogany, comprehending the width of the vessel; a sideboard with liquors, and above it a looking-glass; behind the cabin, an inner room, in which is seated a lady, waiting for the captain to come on board; on each side of this inner cabin, a large and convenient state-room with bed,–the doors opening into the cabin. This cabin is on a level with the quarter-deck, and is covered by the poop-deck. Going down below stairs, you come to the ward-room, a pretty large room, round which are the state-rooms of the lieutenants, the purser, surgeon, etc. A stationary table. The ship’s main-mast comes down through the middle of the room, and Bridge’s chair, at dinner, is planted against it. Wine and brandy produced; and Bridge calls to the Doctor to drink with him, who answers affirmatively from his state-room, and shortly after opens the door and makes his appearance. Other officers emerge from the side of the vessel, or disappear into it, in the same way. Forward of the wardroom, adjoining it, and on the same level, is the midshipmen’s room, on the larboard side of the vessel, not partitioned off, so as to be shut up. On a shelf a few books; one midshipman politely invites us to walk in; another sits writing. Going farther forward, on the same level, we come to the crew’s department, part of which is occupied by the cooking-establishment, where all sorts of cooking is going on for the officers and men. Through the whole of this space, ward-room and all, there is barely room to stand upright, without the hat on. The rules of the quarterdeck (which extends aft from the main-mast) are, that the midshipmen shall not presume to walk on the starboard side of it, nor the men to come upon it at all, unless to speak to an officer. The poop-deck is still more sacred,–the lieutenants being confined to the larboard side, and the captain alone having a right to the starboard. A marine was pacing the poop-deck, being the only guard that I saw stationed in the vessel,–the more stringent regulations being relaxed while she is preparing for sea. While standing on the quarter-deck, a great piping at the gangway, and the second cutter comes alongside, bringing the consul and some other gentleman to visit the vessel. After a while, we are rowed ashore with them, in the same boat. Its crew are new hands, and therefore require much instruction from the cockswain. We are seated under an awning. The guns of the Cyane are medium thirty-two pounders; some of them have percussion locks.

At the Tremont, I had Bridge to dine with me: iced champagne, claret in glass pitchers. Nothing very remarkable among the guests. A wine-merchant, French apparently, though he had arrived the day before in a bark from Copenhagen: a somewhat corpulent gentleman, without so good manners as an American would have in the same line of life, but good-natured, sociable, and civil, complaining of the heat. He had rings on his fingers of great weight of metal, and one of them had a seal for letters; brooches at the bosom, three in a row, up and down; also a gold watch-guard, with a seal appended. Talks of the comparative price of living, of clothes, etc., here and in Europe. Tells of the prices of wines by the cask and pipe. Champagne, he says, is drunk of better quality here than where it grows.–A vendor of patent medicines, Doctor Jaques, makes acquaintance with me, and shows me his recommendatory letters in favor of himself and drugs, signed by a long list of people. He prefers, he says, booksellers to druggists as his agents, and inquired of me about them in this town. He seems to be an honest man enough, with an intelligent face, and sensible in his talk, but not a gentleman, wearing a somewhat shabby brown coat and mixed pantaloons, being ill-shaven, and apparently not well acquainted with the customs of a fashionable hotel. A simplicity about him that is likable, though, I believe, he comes from Philadelphia.–Naval officers, strolling about town, bargaining for swords and belts, and other military articles; with the tailor, to have naval buttons put on their shore-going coats, and for their pantaloons, suited to the climate of the Mediterranean. It is the almost invariable habit of officers, when going ashore or staying on shore, to divest themselves of all military or naval insignia, and appear as private citizens. At the Tremont, young gentlemen with long earlocks,–straw hats, light, or dark-mixed.–The theatre being closed, the play-bills of many nights ago are posted up against its walls.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

“New literary forms always produce new forms of life” (From Chekhov’s Note-Books)

* * * * *

In the servants’ quarters Roman, a more or less dissolute peasant, thinks it his duty to look after the morals of the women servants.

* * * * *

A large fat barmaid—a cross between a pig and white sturgeon.

* * * * *

At Malo-Bronnaya (a street in Moscow). A little girl who has never been in the country feels it and raves about it, speaks about jackdaws, crows and colts, imagining parks and birds on trees.

* * * * *

Two young officers in stays.

* * * * *

A certain captain taught his daughter the art of fortification.

* * * * *

New literary forms always produce new forms of life and that is why they are so revolting to the conservative human mind.

* * * * *

A neurasthenic undergraduate comes home to a lonely country-house, reads French monologues, and finds them stupid.

* * * * *

People love talking of their diseases, although they are the most uninteresting things in their lives.

* * * * *

An official, who wore the portrait of the Governor’s wife, lent money on interest; he secretly becomes rich. The late Governor’s wife, whose portrait he has worn for fourteen years, now lives in a suburb, a poor widow; her son gets into trouble and she needs 4,000 roubles. She goes to the official, and he listens to her with a bored look and says: “I can’t do anything for you, my lady.”

* * * * *

Women deprived of the company of men pine, men deprived of the company of women become stupid.

* * * * *

Six Notes from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books

A letter, written a century or more ago, but which has never yet been unsealed.

A partially insane man to believe himself the Provincial Governor or other great official of Massachusetts. The scene might be the Province House.

A dreadful secret to be communicated to several people of various characters,–grave or gay, and they all to become insane, according to their characters, by the influence of the secret.

Stories to be told of a certain person’s appearance in public, of his having been seen in various situations, and of his making visits in private circles; but finally, on looking for this person, to come upon his old grave and mossy tombstone.

The influence of a peculiar mind, in close communion with another, to drive the latter to insanity.

To look at a beautiful girl, and picture all the lovers, in different situations, whose hearts are centred upon her.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

“Only the useless is pleasurable” and other notes from Chekhov

* * * * *

The hen sparrow believes that her cock sparrow is not chirping but singing beautifully.

* * * * *

When one is peacefully at home, life seems ordinary, but as soon as one walks into the street and begins to observe, to question women, for instance, then life becomes terrible. The neighborhood of Patriarshi Prudy (a park and street in Moscow) looks quiet and peaceful, but in reality life there is hell.

* * * * *

These red-faced young and old women are so healthy that steam seems to exhale from them.

* * * * *

The estate will soon be brought under the hammer; there is poverty all round; and the footmen are still dressed like jesters.

* * * * *

There has been an increase not in the number of nervous diseases and nervous patients, but in the number of doctors able to study those diseases.

* * * * *

The more refined the more unhappy.

* * * * *

Life does not agree with philosophy: there is no happiness which is not idleness and only the useless is pleasurable.

* * * * *

The grandfather is given fish to eat, and if it does not poison him and he remains alive, then all the family eat it.

* * * * *

A correspondence. A young man dreams of devoting himself to literature and constantly writes to his father about it; at last he gives up the civil service, goes to Petersburg, and devotes himself to literature—he becomes a censor.

* * * * *