On another distant December when the house was inaugurated, he had seen from that terrace the line of the hallucinated isles of the Antilles which someone pointed out to him in the showcase of the sea, he had seen the perfumed volcano of Martinique, over there general, he had seen the tuberculosis hospital, the gigantic black man with a lace blouse selling bouquets of gardenias to governors’ wives on the church steps, he had seen the infernal market of Paramaribo, there general, the crabs that came out of the sea and up through the toilets, climbing up onto the tables of ice cream parlors, the diamonds embedded in the teeth of black grandmothers who sold heads of Indians and ginger roots sitting on their safe buttocks under the drenching rain, he had see the solid gold cows on Tanaguarena beach general, the blind visionary of La Guayra who charged two reals to scare off the blandishments of death with a one-string violin, he had seen Trinidad’s burning August, automobiles going the wrong way, the green Hindus who shat in the middle of the street in front of their shops with genuine silkworm shirts and mandarins carved from the whole tusk of an elephant, he had seen Haiti’s nightmare, its blue dogs, the oxcart that collected the dead off the streets at dawn, he had seen the rebirth of Dutch tulips in the gasoline drums of Curacao, the windmill houses with roofs built for snow, the mysterious ocean liner that passed through the center of the city among the hotel kitchens, he had seen the stone enclosure of Cartagena de Indias, its bay closed off by a chain, the light lingering on the balconies, the filthy horses of the hacks who still yawned for the viceroys’ fodder, its smell of shit general sir, how marvelous, tell me, isn’t the world large, and it was, really, and not just large but insidious, because if he went up to the house on the reefs in December it was not to pass the time with those refugees whom he detested as much as his own image in the mirror of misfortune but to be there at the moment of miracles when the December light came out, mother—true and he could see once more the whole universe of the Antilles from Barbados to Veracruz, and then he would forget who had the double-three piece and go to the overlook to contemplate the line of islands as lunatic as sleeping crocodiles in the cistern of the sea, and contemplating the islands he evoked again and relived that historic October Friday when he left his room at dawn and discovered that everybody in the presidential palace was wearing a red biretta, that the new concubines were sweeping the parlors and changing the water in the cages wearing red birettas, that the milkers in the stables, the sentries in their boxes, the cripples on the stairs and the lepers in the rose beds were going about with the red birettas of a carnival Sunday, so he began to look into what had happened to the world while he was sleeping for the people in his house and the inhabitants of the city to be going around wearing red birettas and dragging a string of jingle bells everywhere, and finally he found someone to tell him the truth general sir, that some strangers had arrived who gabbled in funny old talk because they made the word for sea feminine and not masculine, they called macaws poll parrots, canoes rafts, harpoons javelins, and when they saw us going out to greet them and swim around their ships they climbed up onto the yardarms and shouted to each other look there how well-formed, of beauteous body and fine face, and thick-haired and almost like horsehair silk, and when they saw that we were painted so as not to get sunburned they got all excited like wet little parrots and shouted look there how they daub themselves gray, and they are the hue of canary birds, not white nor yet black, and what there be of them, and we didn’t understand why the hell they were making so much fun of us general sir since we were just as normal as the day our mothers bore us and on the other hand they were decked out like the jack of clubs in all that heat, which they made feminine the way Dutch smugglers do, and they wore their hair like women even though they were all men and they shouted that they didn’t understand us in Christian tongue when they were the ones who couldn’t understand what we were shouting, and then they came toward us in their canoes which they called rafts, as we said before, and they were amazed that our harpoons had a shad bone for a tip which they called a fishy tooth, and we traded everything we had for these red birettas and these strings of glass beads that we hung around our necks to please them, and also for these brass bells that can’t be worth more than a penny and for chamber pots and eyeglasses and other goods from Flanders, of the cheapest sort general sir, and since we saw that they were good people and men of good will we went on leading them to the beach without their realizing it, but the trouble was that among the I’ll swap you this for that and that for the other a wild motherfucking trade grew up and after a while everybody was swapping his parrots, his tobacco, his wads of chocolate, his iguana eggs, everything God ever created, because they took and gave everything willingly, and they even wanted to trade a velvet doublet for one of us to show off in Europeland, just imagine general, what a wild affair, but he was so confused that he could not decide whether that lunatic business came within the incumbency of his government, so he went back to his bedroom, opened the window that looked out onto the sea so that perhaps he might discover some new light to shed on the mix-up they had told him about, and he saw the usual battleship that the marines had left behind at the dock, and beyond the battleship, anchored in the shadowy sea, he saw the three caravels.

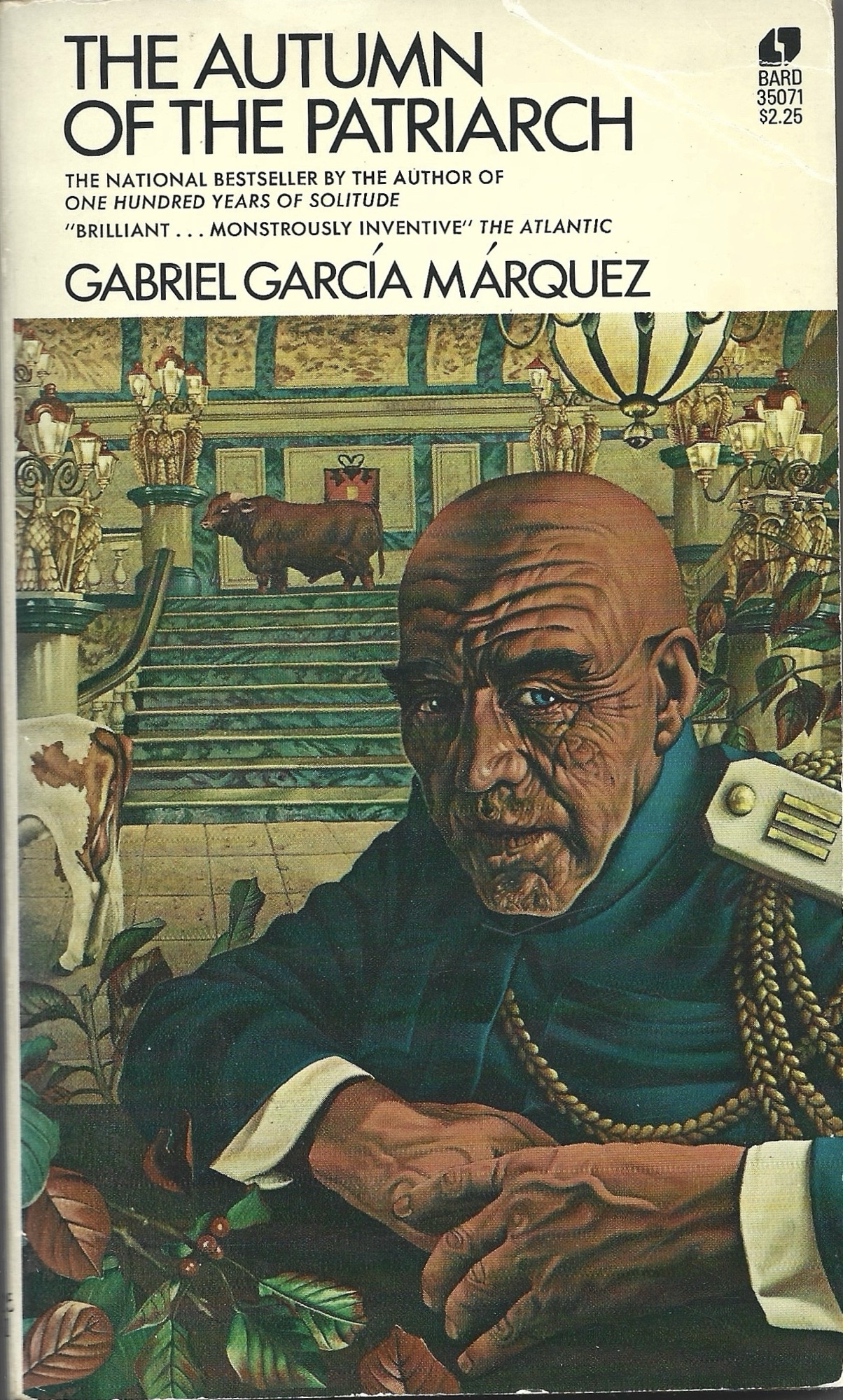

From Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch in translation by Gregory Rabassa.