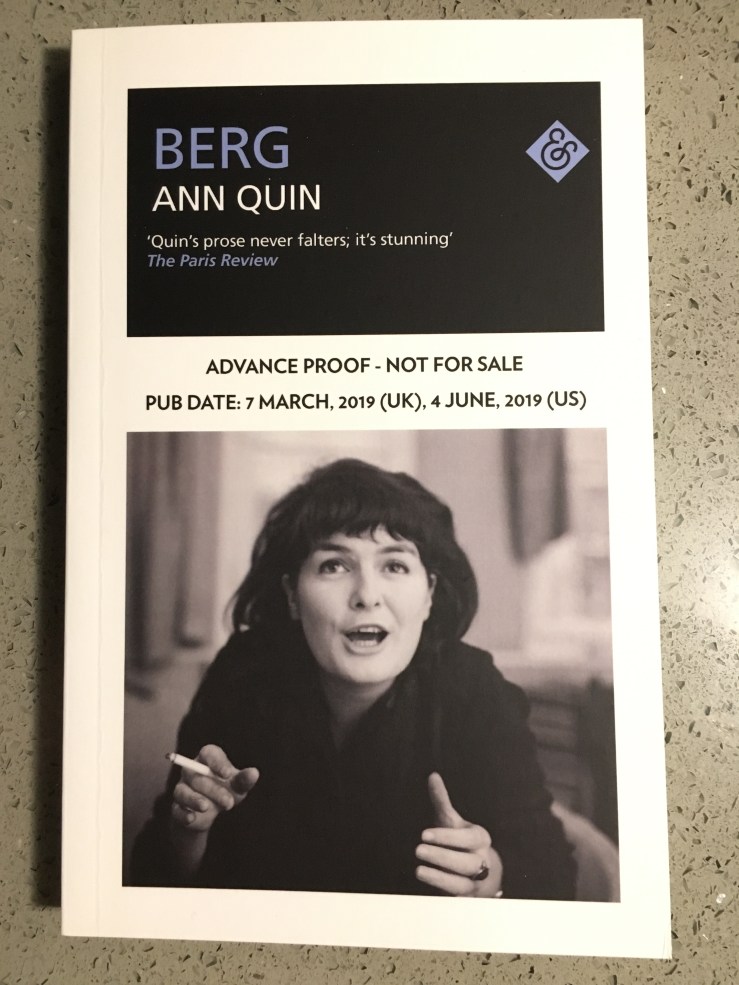

Ann Quin’s 1964 novel, Berg, is in print again from And Other Stories. I’m psyched for this one—Quin is a writer I’ve wanted to read for a while now. Here is And Other Stories’ blurb:

‘A man called Berg, who changed his name to Greb, came to a seaside town intending to kill his father . . .’

So begins Ann Quin’s madcap frolic with sinister undertones, a debut ‘so staggeringly superior to most you’ll never forget it’ (The Guardian). Alistair Berg hears where his father, who has been absent from his life since his infancy, is living. Without revealing his identity, Berg takes a room next to the one where his father and father’s mistress are lodging and he starts to plot his father’s elimination. Seduction and violence follow, though not quite as Berg intends, with Quin lending the proceedings a delightful absurdist humour.

Anarchic, heady, dark, Berg is Quin’s masterpiece, a classic of post-war avant-garde British writing, and now finally back in print after much demand.

Here are the first four paragraphs:

A man called Berg, who changed his name to Greb, came to a seaside town intending to kill his father . .

Window blurred by out of season spray. Above the sea, overlooking the town, a body rolls upon a creaking bed: fish without fins, flat-headed, white-scaled, bound by a corridor room—dimensions rarely touched by the sun—Alistair Berg, hair-restorer, curled webbed toes, strung between heart and clock, nibbles in the half light, and laughter from the dance hall opposite. Shall I go there again, select another one? A dozen would hardly satisfy; consolation in masturbation, pornographic pictures hanging from branches of the brain. WANTED one downy, lighthearted singing bird to lay, and forget the rest. A week spent in an alien town, yet no further progress—the old man not even approached, and after all these years, the promises, plans, the imaginative pursuit as static as a dream of yesterday. The clean blade of a knife slicing up the partition that divides me from them. Oh yes I have seen you with her—she who shares your life now, fondles you, laughs or cries because of you. Meeting on the stairs, at first the hostile looks, third day: acknowledgment. A new lodger, let’s show him the best side. Good morning, nice day. Good afternoon, cold today. His arm linked with hers. As they passed Berg nodded, vaguely smiled, cultivating that mysterious air of one pretending he wishes to remain detached, anonymous. Afterwards their laughter bounced back, broke up the walls, split his door; still later the partition vibrated, while he paced the narrow strip of carpet between wardrobe and bed, occasionally glimpsing the reflection of a thin arch that had chosen to represent his mouth. Rummaging under the mattress Berg pulled out the beer-stained piece of newspaper, peered at the small photograph.

Oh it’s him Aly, no mistaking your poor father. How my heart turned, fancy after all this time, and not a word, and there he is, as though risen from the dead. That Woman next to him Aly, who do you suppose she is?

He had noticed the arm clinging round the fragile shoulders; his father’s mistress, or just a friend? hardly when—well when the photo showed their relationship to be of quite an affectionate nature. Now he knew. It hadn’t taken long to inveigle his way into the same house, take a room right next to theirs. Yes he had been lucky, everything had fallen into place. No hardship surely now in accepting that events in consequence, in their persistent role of chance and order, should slow down?