I’m quite a bit further into the novel than where I’m going to have to leave off in these notes, but there will not be any so-called spoilers/discussion of material past Chapter 14

My general take on Shadow Ticket though: This is probably Pynchon’s most accessible novel. It’s fun, funny, and breezy, but it also kinda sorta bridges Against the Day to Gravity’s Rainbow — and not just in a timeline sense, but also thematically.

Chapter 8:

Hicks’s protege Skeet brings Hicks down to the “clubhouse” under the Holton Street Viaduct. Pynchon continues to develop the glow-in-the dark horror film motif, describing, “Cobwebs of purple light from radio tubes with imperfect vacuums inside…A dozen speakers going at once…Pieces of electrical gear blinking and chirping at each other, like a lab in a movie belonging to a scientist not entirely in his right mind.”

The mad scientist monitoring all these wild signals is pretty harmless though. It’s “a kid named Drover in a set of earphones.” Drover shows off the amplified ukulele he’s crafted: “Kid out in Waukesha showed me…You want the real Tom Swift, it’s this Lester kid, calls himself Red, playing hillbilly guitar up and down Bluemound Road for nickels and dimes, drive-ins, roadhouse parking lots, gets to where he needs to be heard over the traffic, so he figured this out.”

This Lester aka Rhubarb Red is, of course, Les Paul, whose artistic and technological contributions and innovations to 20th-century popular music cannot be overstated. I think his licks sound fresh today.

Pynchon has long been concerned with the intersection of art and technology; of how a signal can cut through noise.

Skeet has brought Hicks to the “clubhouse” under the viaduct to connect with Stuffy Keegan, whose REO Speed Wagon was exploded by unknown entities in Shadow Ticket’s opening chapter. Things get very, very Pynchonian here—a U-13 submarine is prowling the depths of Lake Michigan, apparently there to pick up Stuffy. Hicks is in disbelief. Drover has a hard time picking up a human voice from the sub, and declares that, “everybody must be down below at the bowling alley.” Hicks is even more incredulous: “Bowling alley on a submarine, Drover?” — setting up an execrable/wonderful Pynchonian joke that pivots on a Jules Verne novel’s title.

The episode ends with Stuffy disappearing somewhere, although Hicks is loath to believe he left on a submarine. Chapter 8 concludes with a less-skeptical Skeet pointing out that Stuffy “Kept saying things like ‘Maybe I’m a ghost now and I’m haunting you,’” again underscoring the novel’s horror-film motif.

Chapter 9 might be summarized by its opening line: “Skeet shows up at the office next day with an out-of-town tomato who causes a certain commotion.”

This fair lady is one “Fancy Vivid” (geez Thomas); no one in the detective agency can quite believe that she wants to hire them to find disappeared Stuffy, whom she loves dearly. She’s hip to the submarine thing too: “He ever say anything to you about a submarine? …Kept wanting to know if I’d ever been on one, if I’d like to go for a ride on one. At first I thought it was some kind of sex talk.”

Like the previous chapter, this one ends with a Gothic note. Hicks goes into a reverie while looking through old files, dreams he’s “in Chicago, or something calling itself that, up North Clark, across the suicides’ bridge, deep in that part of the North Side known as The Shadows.” In this space that is “haunted to saturation by the unquiet spirits of hanged men and women, white, Negro, and American Indian,” he encounters too the spirit of Stuffy who pleads for his help. “Only a dream,” Hicks tells himself.

Chapter 10:

When we first met Hicks’s Uncle Lefty back in Ch. 4, he espoused his sympathies for Adolf Hitler; in Ch. 10, after a casserole dinner, he takes his nephew to a Nazi bar, the New Nuremberg Lanes. Hicks, as yet unaware of the bar’s fascist sympathies, nevertheless picks up on the weird vibes:

“All normal as club soda, yet somehow…too normal, yes something is making a chill creep across Hicks’s scalp, the Sombrero of Uneasiness, as it’s known in the racket. Something here is off. A bowling alley is supposed to be an oasis of beer and sociability, busy with cheerful keglers, popcorn by the bucketful, crosscurrents of flirtation, now and then somebody actually doing some bowling. But this crowd here, no, these customers are only pretending to bowl…”

These people are all American Nazis.

Hicks runs into Ooly Schaufl (“Going by Ulrich these days”), an old associate from his strike-breaking day. The scene underlines a theme developing in the novel: Hicks slowly starting to realize which side of the line he belongs on. The reunion is broken up by the Feds though — prohis, dry agents, in the novel’s parlance.

Hicks makes his escape. At the next casserole night, Uncle Lefty gives Hicks the plot-moving-forward tip that Pynchon has frequently deployed thus far in Shadow Ticket, telling him to check out the under-radar as-yet-unopened FBI office in Milwaukee.

Chapter 11 begins with more Gothic intentions; Hicks approaches local the local FBI headquarters, which appears something closer to a haunted house:

“On days of low winter light the federal courthouse can take on a sinister look, a setting for a story best not told at bedtime, the jagged profile of an evil castle against pale light reflected off the Lake, bell tower, archways, gargoyles, haunted shadows, Halloween all year long.”

In Shadow Ticket, the goofy Gothicism of glaring gargoyles butts up against the realer, deeper horror of encroaching fascism abroad and a burgeoning police state at home — and worse, the twisting, bundling of these forces. Hicks gets twisted into it; the feds want him to be their agent too.

Chapter 12 begins with Hicks’s boss Boynt going full tilt paranoid, Pynchonian style:

“The federals who had you in are likely just a front, OK? It’s the outfit that’s behind them, a nationwide syndicate of financial tycoons, all organized in constant touch against the forces of evil, namely everything to the left of Herbert Hoover. Worried about the next election, worried this latest Roosevelt if he gets in might decide to step out on his own, and even if he does revert to type after all, it might not be in time to stop the Red apocalypse that’s got them spooked out of what they think of as their wits.”

The outfit, the syndicate–Boynt ties the forces of right-wing capitalism to outright fascist gangsterism. He redirects his detective’s attention to the cheese heiress case, and the pair take off to the Airmont’s lawyers’ office. There, Hicks is asked if he’s “aware of the American Indian belief, referenced in depositions filed on Miss Airmont’s behalf, that once you save somebody’s life, you’re responsible for them in perpetuity?” (This routine gets brought up again and again.)

Chapter 13:

Hicks heads out to the Airmont mansion to do some recon on missing heiress Daphne. There, he picks up on chatter about “the recent Bruno Airmont Dairy Metaphysics Symposium held annually at the Department of Cheese Studies at the UW branch in Sheboygan, this year featuring the deep and perennial question, ‘Does cheese, considered as a living entity, also possess consciousness?'”

The philosophical riffing gives way to a brief overview of the Airmont cheese fortune, which was built in no small part upon the brief success of a product called “Radio-Cheez…designed to stay fresh forever, in or out of the icebox, thanks to a secret, indeed obsessionally proprietary, radioactive ingredient.”

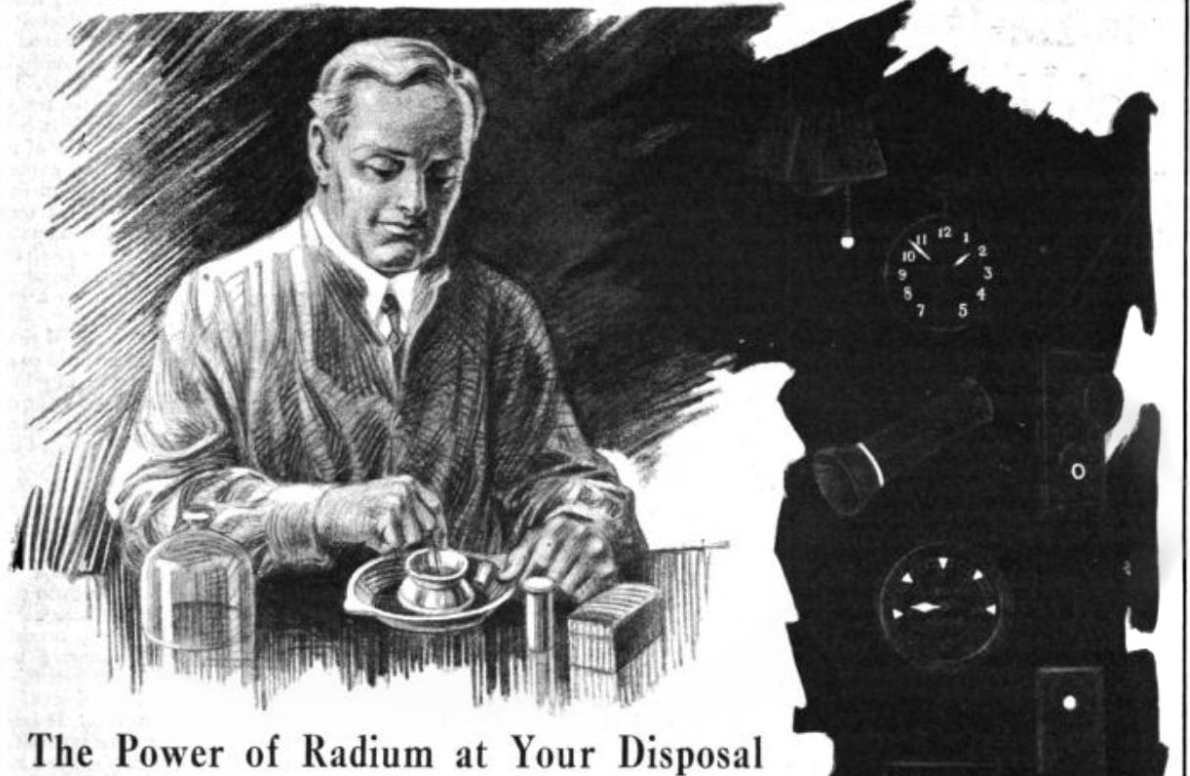

The narrator reminds us that this was “radium’s grand hour of popularity, when it’s still medical wisdom to seek as many ways as possible to introduce radiation into the human body—radioactive mineral water, patent radium elixirs and aphrodisiacs, radium suppositories,” before bringing up the “Radium Girls” of “nearby Ottawa, Illinois [who] were employed in painting numbers on glow-in-the-dark clock dials, licking their brushes every so often to keep them finely pointed.”

The sad story of the Radium Girls has been well documented. It is another case of real-life horror in Shadow Ticket butting up against Pynchon’s zanier play-acting theatrical horrors. The Radium Girls’ case eventually led to expanded labor protections in the United States, making them ideal Pynchonian heroes.

Cheese conspiracies develop in this chapter; we learn that “The year 1930 happened to be the 1776 of the cheese business.” Bruno Airmont, the “Al Capone of Cheese” befriends the Al Capone (“And what is it you’re the Al Capone of again?”).

At the Airmont compound we also meet G. Rodney Flaunch, “a onetime male flapper” and fiancé to departed Daphne and mom, Mrs. Vivacia Airmont.

And in Chapter 14 we finally get the backstory of Hicks and Daphne’s meet-cute. Daphne’s in disguise and on the run from “Winnetka Shores Psychopathic, a ritzy banana plantation in the neighborhood, overseen by a Dr. Swampscott Vobe, M.D. Known for a susceptibility to anything newfangled, Dr. Vobe has somehow gotten it into his head that the patients at WSP are all available to him as lab material to try out his therapy ideas on, free of charge. Drugs, electricity, rays. Dr. Vobe is specially interested in rays.”

More mad scientist Halloween-all-the-time shit. They escape via rumrunner–the boat, not the drink–and Hicks drops the heiress at an Ojibwe reservation (she claims it was her finishing school). There are more horror notes — references to werewolves and windigos — and again the note that if you save a person’s life you are forever responsible for it:

“And if I say thanks but no thanks, what happens, I get an arrow through my head?”

“You don’t have to be all that way about it either, white man.”

I’ve left out noting all the drinks in Shadow Ticket thus far — I leave that task for Drunk Pynchon! — but I have to bring up two from this chapter. The first is Hicks’s Old Log Cabin Presbyterian, which sounds fucking delicious. The second is Dippy Chazz’s Wisconsin Old Fashioned: “Korbel brandy, 7UP lithiated lemon soda, and, sharing the toothpick with a cherry, a pickled Brussels sprout.” Initially, I thought this had to be a Pynchonian invention — but it’s not. From Toby Cecchini’s case study of the cocktail in The New York Times:

It’s more a family of drinks, revolving around a central theme. There are four main ways to order it: sweet, with 7 Up; sour (which is not), with sour mix or Squirt; “press” with half 7 Up and half seltzer; or seltzer only. There are regional garnish customizations using pickled vegetables — including mushrooms, asparagus, cucumbers, tomatoes, brussels sprouts and olives — that seem counterintuitive until you taste the salty, vinegar tang playing off of the spice of the bitters and the sweet thrum of the brandy. By God, our great-grandparents were on to something.

Never heard of this novel. Have to check it out. Stopped reading your review in the middle because I was afraid of too much spoilers. Sounds anyway as a great review since it made me consider this Pynchon.

LikeLike

…you had me at Wisconsin Old Fashioned (both husbands, Milwaukee natives).

Just back to Chicago, so gotta catch up. And hit the streets.

I’ve been off the grid upstate for weeks (NY), breaking rock (literally) to help the kids rehabilitate an abandoned Hollenbeck they managed to buy from the daughter of folks that had it built for weekends, right about the same time I graduated high school in L.A.

PS: personally, I’m a gin girl… but, still.

KME

PPS: Same boots for fifty+ years… mink oil works. And Vibram is a real thing,

LikeLike

Loving your notes so far! And man I would have loved to start my Shadow Ticket drinking with that Wisconsin Old Fashioned, brussel sprout and all, only it seems Korbel brandy is Not So Easy to get a hold of down here in Australia. But I will manage it sooner or later. Keep up the good work!

LikeLike