Don’t forget the real business of the War is buying and selling 1. The murdering and the violence are self-policing, and can be entrusted to non-professionals. The mass nature of wartime death is useful in many ways 2. It serves as spectacle, as diversion from the real movements of the War. It provides raw material to be recorded into History, so that children may be taught History as sequences of violence, battle after battle, and be more prepared for the adult world 3. Best of all, mass death’s a stimulus 4 to just ordinary folks, little fellows 5, to try ’n’ grab a piece of that Pie while they’re still here to gobble it up. The true war is a celebration of markets 6. Organic markets, carefully styled “black” 7 by the professionals, spring up everywhere. Scrip, Sterling, Reichsmarks continue to move, severe as classical ballet, inside their antiseptic marble chambers. But out here, down here among the people, the truer currencies come into being. So, Jews are negotiable. Every bit as negotiable as cigarettes, cunt, or Hershey bars. Jews also carry an element of guilt, of future blackmail, which operates, natch, in favor of the professionals. 8

From page 105 of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

1 Gravity’s Rainbow is often (unjustly and unfairly) maligned as a messy, even pointless affair—but here’s our author speaking through the narrator, offering up one of the novel’s points—clearly, without equivocation.

2 Our narrator digs irony though…

3 Entropy is all—but entropy doesn’t make for good capitalism, by which our sly narrator means, Their Capitalism. The adult world needs to be organized, systematized, caused and effected.

Cf. Jack Gibbs’s rant to his erstwhile young students, early in William Gaddis’s 1975 novel of capitalism, J R:

Before we go any further here, has it ever occurred to any of you that all this is simply one grand misunderstanding? Since you’re not here to learn anything, but to be taught so you can pass these tests, knowledge has to be organized so it can be taught, and it has to be reduced to information so it can be organized do you follow that? In other words this leads you to assume that organization is an inherent property of the knowledge itself, and that disorder and chaos are simply irrelevant forces that threaten it from the outside. In fact it’s the opposite. Order is simply a thin, perilous condition we try to impose on the basic reality of chaos . . .

4 Note the not-so-oblique reference to GR’s theme of stimulus-response (and upending that response).

Not too much earlier in the narrative, dedicated Pavlovian Dr. Edward W.A. Pointsman worries about the end of cause and effect, the rise of entropy:

Will Postwar be nothing but ‘events,’ newly created one moment to the next? No links? Is it the end of history?

5…the preterite?

6 Pynchon reiterates his thesis.

7 Note that organic (entropic?) markets fall outside of Their System—y’know, Them—the Professionals—these organic (chaotic, necessary) markets must be labeled “black” (preterite?).

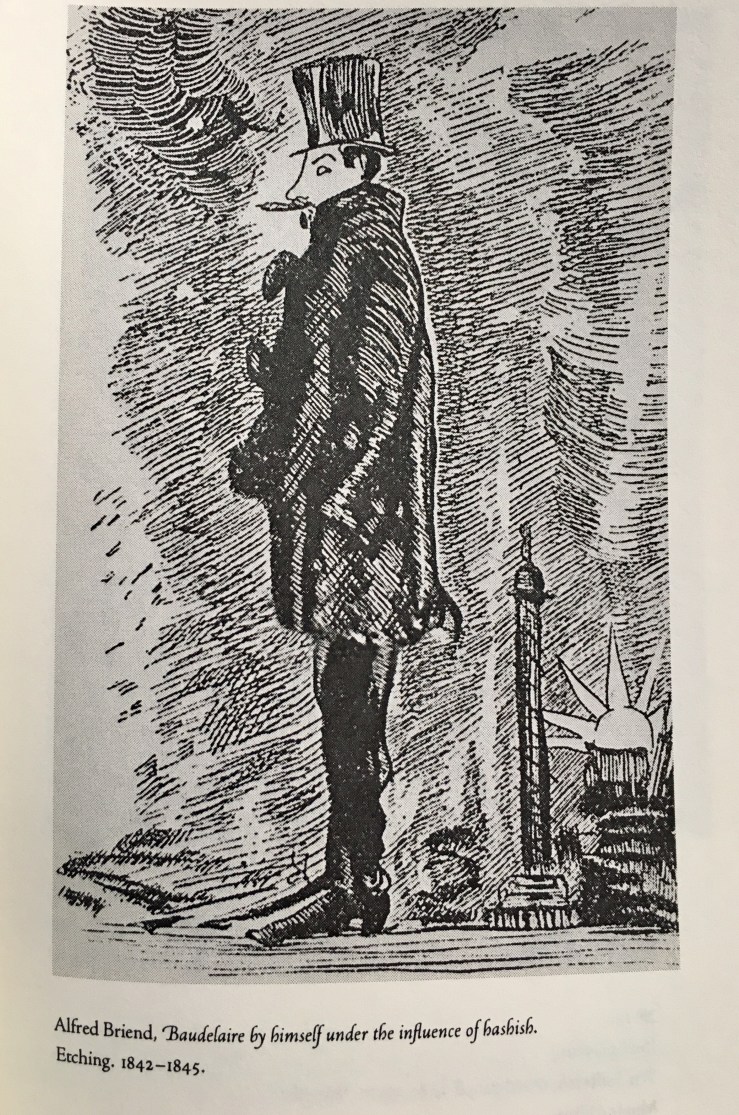

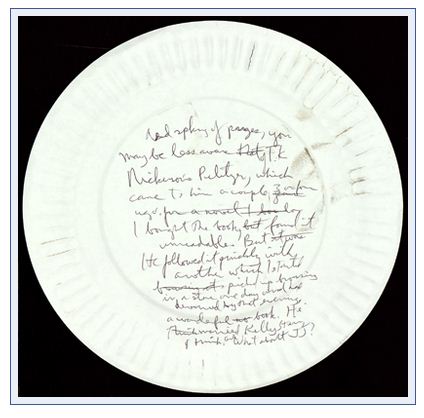

Here’s another Dutch propaganda poster:

Page 105 of Gravity’s Rainbow “happens,” more or less, in 1944, in the middle of an extended introduction of Katje Borgesius, a Dutch double agent. (Or is that double Dutch agent?). The propaganda poster above strikes me as overtly racist, but also seems to nod to King Kong (1933, dir. Cooper and Schoedsack). Gravity’s Rainbow is larded with references to King Kong, a sympathetic but powerful force of entropy, a force against the Professionals.

From the invaluable annotations at Pynchon Wiki’s Gravity’s Rainbow site (there is no annotation for page 105 at Pynchon Wiki, by the way, and no notes on the passage I’ve cited above either in Steven Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion):

King Kong & the Like

Fay Wray look, 57; Fay Wray, 57, 179, 275; “You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood,” 179; “headlights burning like the eyes of” 247; “the black scapeape we cast down like Lucifer,” 275; Mitchell Prettyplace book about, 275; “Giant ape” 276; “the Fist of the Ape,” 277; “orangutan on wheels,” 282; taking a shit, 368; “The figures darkened and deformed, resembling apes” 483; “a troupe of performing chimpanzees” 496; “on the tit with no motor skills,” 578; “Negroid apes,” 586; “that sacrificial ape,” 664; “a gigantic black ape,” 688; Carl Denham, 689; poem based on King Kong, 689; See also: actors/directors film/cinema references;

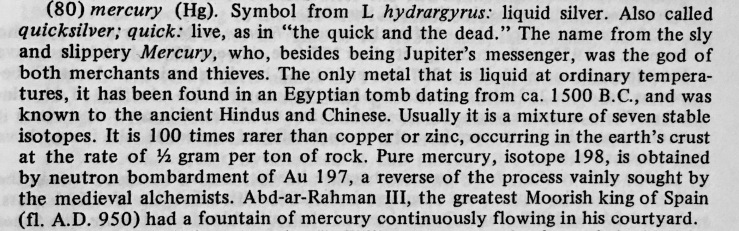

The Kong-figure in the Dutch propaganda poster seems to wear the petasos (winged hat) and wield the caduceus of Hermes or Mercury—god of thieves. But also god of the market, of commerce, merchandise, all things mercenary.

From Joseph T. Shipley’s The Origin of English Words: A Discursive Dictionary of Indo-European Roots (1984):

8 The passage as a whole, which emphasizes war as a conduit for the techne of the market (or do I have that backwards? should I note the market of techne?) echoes an earlier passage. From page 81:

It was widely believed in those days that behind the War—all the death, savagery, and destruction—lay the Führer-principle. But if personalities could be replaced by abstractions of power, if techniques developed by the corporations could be brought to bear, might not nations live rationally? One of the dearest Postwar hopes: that there should be no room for a terrible disease like charisma.

All signs seem to point to No.