We know Sarah Palin loves to read. In a great op/ed piece in today’s Washington Post, Ruth Marcus writes:

Asked in an interview for PBS’s Charlie Rose show last year (http://www.charlierose.com/guests/sarah-palin) about her favorite authors, Palin cited C.S. Lewis — “very, very deep” — and Dr. George Sheehan, a now-deceased writer for Runner’s World magazine whose columns Palin still keeps on hand.

“Very inspiring and very motivating,” she said. “He was an athlete and I think so much of what you learn in athletics about competition and healthy living that he was really able to encapsulate, has stayed with me all these years.”

Also, she got a Garfield desk calendar for Christmas 1987 that made a big impression.

Great stuff. Who doesn’t love to read? Books is where you gets knowledge. However, Palin is the sort of fundamentalist hardliner who thinks she knows what’s best for all of us to read–or not read. By now, you’ve probably heard of the pressure Palin exerted on the librarian of Wasilla. As mayor, Palin inquired how she might go about removing books from the library. Of course, according to most reports, including this one from The Anchorage Daily News earlier this month, “Palin didn’t mention specific books at that meeting.”

Huh. Hard to imagine that Palin didn’t get specific, right?

Palin then wrote the librarian in question a letter telling her she would be fired for lack of loyalty. Although public outcry prevented the firing, the librarian eventually moved away from Wasilla. Palin said at the time, and has maintained since then, that the question was “rhetorical”; she simply wanted to know how one would go about removing “objectionable” books.

Why would you ask how to remove books if you had no intention of removing them?

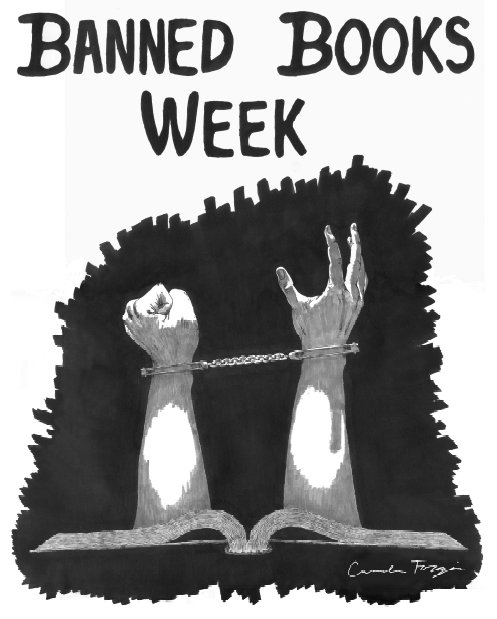

It’s too easy to dismiss Palin’s inquiries into censorship. Her moralistic will to ban what others read is really an attempt to control ideas, to control thoughts, to control bodies even–the ultimate goal of the far Christian right. It’s the middle of Banned Book’s Week, and it’s time to say “No” to the vacuous (a)moralizing of those like Palin who would presume to dictate what is and is not acceptable to be loaned in a public library. I don’t know about you, but I’m not going to let a woman who apparently believes that “dinosaurs and humans walked the Earth at the same time” tell me what to think or feel or read.

Banned Books Week calls attention to not only the great currency of ideas we have in literature, but to also points out that there are still those who seek to suppress ideas with which they don’t agree. Even as we celebrate these books, we must attack those who would ban them–especially those who work so surreptitiously.