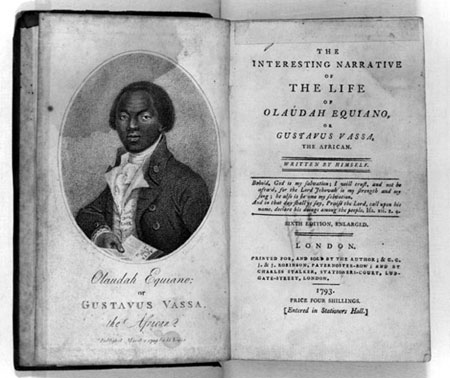

I’ve been re-reading Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, a fascinating autobiography/travel book detailing Equiano’s experiences being kidnapped from West Africa at a young age and sold into slavery. During this time, Equiano migrates all around the world, earns and loses and earns again his freedom, and eventually comes to identify himself as an Englishman, replete with English values. Today, the book is widely regarded as a key abolitionist text; it remains a fascinating document of the cruelty and inhumanity of slavery. It’s also a pretty interesting adventure story.

The early part of the book is chock full of images of consumption and sacrifice. Prominent among these images, the threat of cannibalism looms as the ultimate horror at stake in an alien encounter between two different cultures. The first image of cannibalism, however, becomes a sort of baseline of the rhetoric of cannibalism. Equiano relates the following Ibo proverb concerning villagers with bitter tempers: “if they were to be eaten, they were to be eaten with bitter herbs,” noting that many Ibo “offerings [sacrifices] are eaten with bitter herbs.” This seemingly light-hearted proverb locates the consumption of the human body as a site of holy sacrifice, acknowledging that the cost of existence always figures as a displacement of one person’s access to resources in favor of another’s. Equiano later expresses a wish to sacrifice himself to gain his sister’s freedom—“happy should I have ever esteemed myself to encounter every misery for you, and to procure your freedom by the sacrifice of my own,” here echoing the Ibo proverb’s realization of a sacrificial economy. This sacrificial economy plummets into the taboo horror of cannibalism, as a terrified Equiano, kidnapped and dragged to the West African coast, first encounters Europeans. He asks his fellow Africans “if [he] were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair.” The terror of this alien-encounter is not abated when the Africans assure Equiano that he is not to be eaten; “I expected they would sacrifice me,” he writes.

As the horror of his sea voyage increases, so does his belief that he is to be voraciously consumed by his captors. While “all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold,” Equiano avers that “We thought […] we should be eaten by these ugly men.” Equiano here figures as a sacrificial lamb, consumed by brutal barbarians. The slave-traders tap into and exploit this fear, using it to manipulate the behavior of Equiano: “the captain and people told me in jest they would kill and eat me, but I thought them in earnest.” Equiano puts his horror even more bluntly: “I very much feared they would kill and eat me.” Equiano’s horror at the threat of cannibalism contrasts greatly with the captain’s playful attitude about the eating of human flesh. The captain “jocularly” threatens to “kill” and “eat” Equiano, and also threatens to eat his young friend as well. The captain then inquires about the cannibalistic practices of West Africans, jokingly averring that “black people were not good to eat,” thus implying he had tasted their flesh before. The captain’s rhetorical technique further destabilizes Equiano’s sense of safety as well as confounding any attempt to systematize knowledge of the ethics, morality, and diet of his new captors; in short, the captain further alienates Equiano’s experience. However, a future Equiano, reflective and knowledgeable, assesses these structures of consumption and sacrifice in terms of economy. “Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice?” Equiano demands of the “nominal Christians” who participate in the slave trade. Equiano thus translates the literal consumption of enslaved labor into the spiritual, emotional consumption that occurs when people cannibalize each other. The captain’s humor—and indeed, the slight and humorous tone of the Ibo proverb—both serve as defense mechanisms to psychologically mask the taboo terror of cannibalism that figuratively underscores the enslavement of human beings.

[…] have been required reading in my high school classroom. I usually emphasize sections from Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass, two masterful writers whose complex syntax and diction can be stunning, if […]

LikeLike

[…] All POWs were eaten, corpses were bought from middle-men for feasts, human skins were used for drums, amongst others. This craving was so bad that the authorities had to deal with several reports of thefts of recently buried corpses. Heads were reserved for the community leaders – outside of their homeland they express their love for consuming isi ewu (goat head); and they even derogatively refer to Yoruba people as ofemanu (red oily brain). Slaves were purchased in numbers for feasts. Olaudah Equiano, a well known Igbo former trans-Atlantic slave, noted in his memoirs that when he was captured in his homeland he concluded that his flesh was going to be eaten. […]

LikeLike