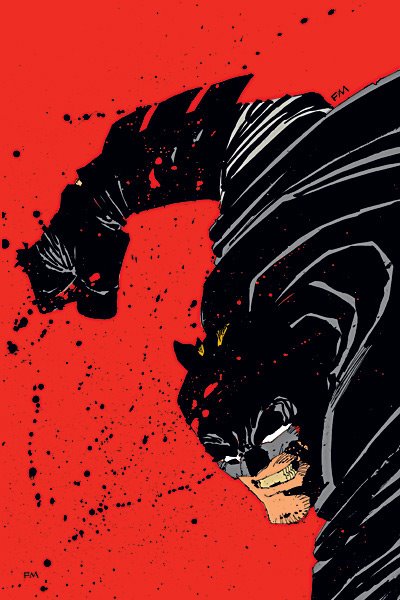

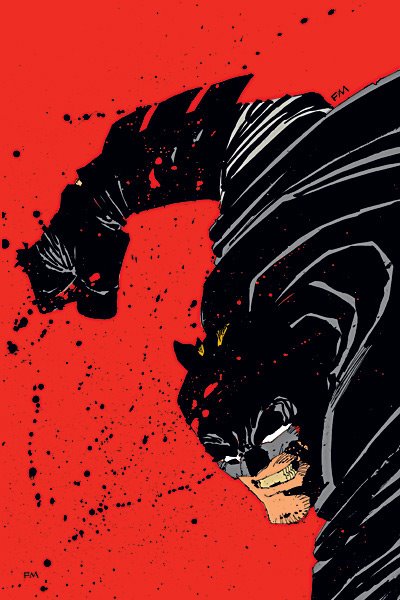

During a horrible illness I suffered the other week, I turned to the only thing that I can digest when I’m really, really sick–comic books. I randomly chose to reread Frank Miller’s classic re-imagining of Batman, 1986‘s The Dark Knight Returns. I’ve read this comic–or “graphic novel,” if you want to sound like an asshole who’s afraid of being seen reading comic books–at least a dozen times now, I’d guess, but the last time I’d read it was after its sequel The Dark Knight Strikes Again came out in 2001.

The Dark Knight Returns didn’t disappoint; it never does. Set in a future with a very old Bruce Wayne, the story figures Gotham City as an urban dystopia, chaotic with child-gangs running rampant. The superheroes that once policed the world–including Superman–have been forced to retire by the government. The anarchy in the city prompts The Batman to return. The Joker revives his old crime career. The Soviets invade a Caribbean island. Superman and Batman fight. Batman leads a youth revolution. It’s really fucking spectacular, grim, violent, and funny–the book works at all times to satire the media-obsessed materialism of the 80s. Great stuff.

I don’t own the sequel, The Dark Knight Strikes Again, which says a lot. The story’s not great; in fact, it’s highly forgettable.The plot overreaches, eschewing the essentially frail humanity of The Batman–always the character’s most interesting facet–in favor for a plot stuffed with too many of the truly extra-human characters of the DC universe. Superman, Brainiac, and Captain Marvel are just too hyperbolic to serve as effective foils for gritty Batman. Fifteen years later, Miller’s sequel overshoots, taking Batman from the underground, from the streets, and up into the air, where he just doesn’t belong.

The Dark Knight Strikes Again also came out after Frank Miller had had tremendous success with his Sin City series, published by Dark Horse. I remember when the first Sin City comics came out: I was really disappointed. The artwork was fantastic–a new level of excellence for Miller, whose Jack Kirby-influenced lines always managed to convey energy, tension, and action. Sin City looked like no comic before it that I can think of, a chiaroscuro film noir that rippled and moved. Unfortunately, the story was basic at best and flat and one-dimensional at worst. Without thematic depth or any measure of subtlety, the Sin City stories are aesthetically pleasing but hardly essential.

When 300 came out as a film last year, I took the time to read it–at Barnes & Nobles. Again, the book, especially in its oversized format, is visually striking, but where the old Frank Miller–the guy who created Elektra and made Wolverine the coolest mutant in the world–would’ve just drawn a great story, the late nineties Miller forces the drama down the reader’s throats. On virtually every page, 300‘s narrator tells you how you should feel about what’s going on in the story; the book is probably better without any lettering at all.

Although 300 was published in 1998, as criticism of the film has shown, its themes of patriarchal violence, unabashed militarism, and outright xenophobia are amazingly prescient to America’s post 9/11 ideology (my biggest criticism is undoubtedly the film’s depictions of idealized bodies contrasted with the extreme vilification of any “othered” bodies: this is a film that hates the differently-abled at all turns). Frank Miller has been something of a spokesman for this gung-ho mentality. Consider his September 11th, 2006 contribution to NPR’s “This I Believe” series, in which he blandly recapitulates the Bush administration’s “with us or against us” (in being against them) ethos; in an interview (again on NPR) a few months later he rails the “Bush-hating” “spoiled brats” who are not on board with the Iraq war. For such comments, Miller’s become something of a hero among right-wing bloggers, and his work has been reinterpreted within this light.

I wouldn’t hold this against Miller if his work held up, but I’m not sure that it does. He hasn’t produced anything that could touch The Dark Knight Returns in the twenty-plus years since its publication, and his recent announcement that he is writing Holy Terror, Batman! a self-described “piece of propaganda” in which “Batman kicks al Qaeda’s ass” is a truly lamentable decision (even Stan Lee, of all people, described the idea as “corny” and out of touch). Miller’s aim to write a piece of “propaganda” seems dead on, actually. Divorce “propaganda” from whatever politics it’s meant to convey, for a moment, and you have exactly the kind of work Miller’s been producing for quite some time now: thoroughly one-dimensional, brutishly simple pulp that hides its vacuity under a thick veneer of stylized violence.

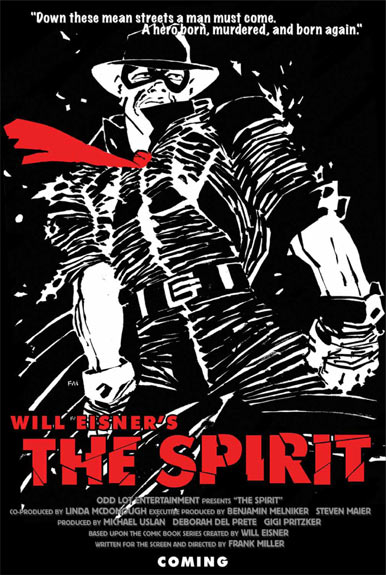

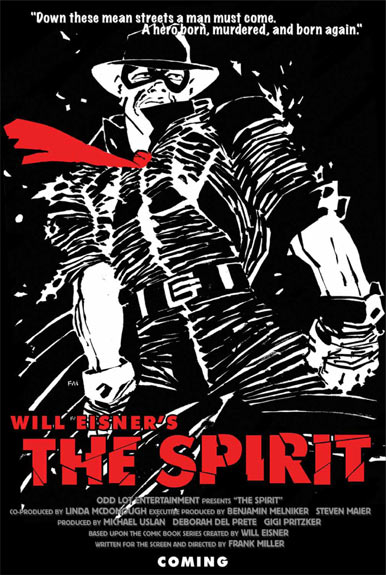

To come back to where this long post started: after I finished The Dark Knight Returns, I reread Ronin, Miller’s 1983 tale of a masterless samurai lost in an apocalyptic future New York. The story explores dystopic race relations, emerging technologies, telekinesis, and bioethics. There’s also a demon. Ronin is cyberpunk on par with the best of William Gibson, and certainly the best thing Miller ever produced–and possibly the most overlooked. Apparently, a film version of Ronin is planned for release in 2009, which will undoubtedly lead to future confusion connected to Frankenheimer’s 1998 car-chase opus (also titled Ronin). Miller, however, seems to have no major hand in the movie–he’s too busy adapting and directing Will Eisner’s classic strip The Spirit for a 2009 movie release. The Spirit is fantastic source material, and Samuel “I Will Act in Your Movie For Money” Jackson is playing the villain, The Octopus, so it might be good. Then again, Miller is the screenwriter responsible for both Robocop 2 and 3, movies that completely missed the tone of Verhoeven’s satirical original. And whether or not Miller’s future movies–including sequels to Sin City–are any good, the gritty and grimy tone that he established in series like Daredevil and the original Wolverine book, as well as his groundbreaking revisioning of Batman led to a new seriousness and depth to an art form that had too-long been relegated to the margins of literature. And that’s a good thing.