A weeks-long back-and-forth with a colleague about certain flavors of Modernist novels led to this colleague, a friend really, to come by my office with a stack of about 80 pages he’d printed, front and back, demanding that I take a look at some utter nonsense, probably the kind of nonsense I’d abide. This particular nonsense was a printed .pdf of Camilo José Cela’s 1988 novel Cristo versus Arizona in the original Spanish. “It’s all just one long sentence!” my colleague declared. I was immediately intrigued, and am still on the lookout for Martin Sokolinsky’s 2007 English translation. Wikipedia, cribbing the Publisher’s Weekly review of that translation describes Christ Versus Arizona as “set in the American Old West during the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in 1881. It consists of a monologue in one long sentence, inside the head of Wendell Liverpool Espana, who is the son of a prostitute and observes the gunfight.” I expressed my delight with the concept. My colleague then reverted to his argument, which, I will badly summarize as something like, All these Modernists tried this nonsense and some point just to show off at the expense of the reader. He extolled again the virtues of Dubliners over Ulysses, a book with its head in its ass; he decried Faulkner’s worst tendencies—a gifted writer who could offer up a perfect novel and then birth an abomination like The Sound and the Fury. Cristo versus Arizona, he assured me, was Cela’s abomination; he then urged me to read Cela’s masterpiece, La colmena, which he translated as The Beehive. And then I had an 11:00am class to attend to.

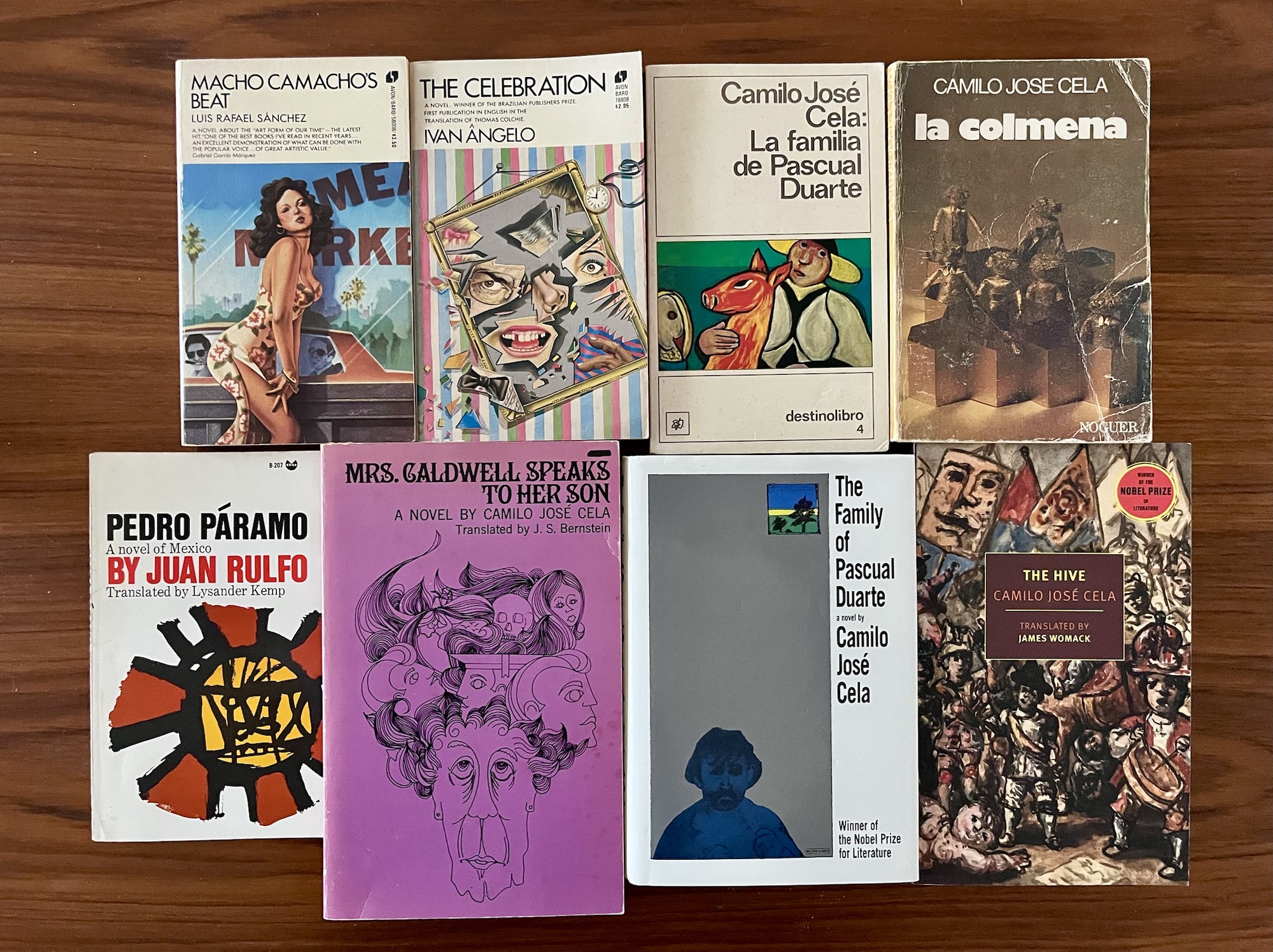

Driving home I realized that I might actually have a copy of an English translation of La colmena. I did: Anthony Kerrigan’s translation, The Hive. I pulled it out, started reading, and kept going. I love it! The next day my colleague brought in two Cela novels he’d read (and annotated the hell out of) in graduate school: La colmena and La familia de Pascual Duarte. I think that was on a Thursday. On Friday I browsed a used bookstore and picked up Kerrigan’s translation of Cela’s The Family of Pascual Duarte (with a cool Milton Glaser cover). I also picked up Ivan Ângelo’s novel The Celebration (in translation by Thomas Colchie); I’ve gotten to the point where I just scoop up any of the Avon Bard Latin American translations when I come across them — which is what I did a week later when I browsed a different used bookstore (or, really, a different location of the same booksellers; I was right next to this location because several of my son’s paintings were exhibited in a gallery nearby as part of a contest he had entered a few months ago without telling us (these details are not important to the story; my son is a talented painter though and I am proud).

Which is what I did a week later, scoop up another Avon Bard Latin American translation — this time Macho Camacho’s Beat by Luis Rafael Sánchez, in translation by Gregory Rabassa. I also picked up Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo (trans. Lysander Kemp), which I’ve been meaning to read for a while now, and another Cela — Mrs. Caldwell Speaks to Her Son (trans. by J. S. Bernstein).

And so well back to Camilo José Cela then–I’m almost finished with The Hive, delayed at times by checking in against the original La colmena, mostly to get a sense of some of choices the translator made, a process I’m looking forward to repeating again with The Family of Pascual Duarte, a process that’s included riffing on the writing with my colleague, my friend who brought by a big stack of papers, a ridiculous pile of papers, that one-word sentence of a novel, Cristo versus Arizona, the novel I would love to acquire soon.