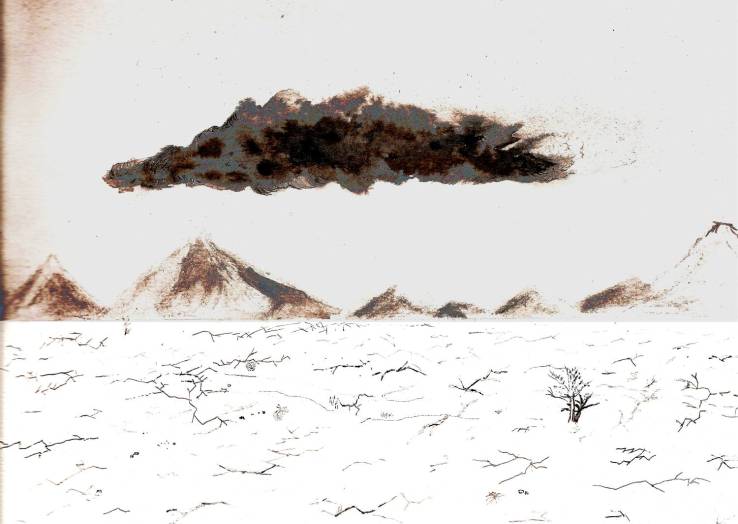

This is the 2nd part of my conversation with Ilan Stavans about The Plain in Flames, his translation of Juan Rulfo’s short story collection El Llano en Llamas. Catch up with part 1 here. Lauren Flinner made the artwork below. (Editor’s note: “Schade” is George D. Schade, who did the first English translation of Juan Rulfo’s short stories as The Burning Plain.)

The goal of putting these stories out in English is to say, “I can’t see the world without them.” I believe that I can dress the stories in a way that is truthful to the original. But now that they’re there, it is up to whomever comes to the text to be able to synchronize with the stories.

Rulfo said, upon finishing Pedro Paramo, “I couldn’t make head nor tail of it, which signaled to me that it was finished.” When did you know you were finished?

I take after Walt Whitman – I know that I am finished when I have finally forced myself to send it to the editor and begin the editorial process, and when (or if) I open it again – as you are making me do right now [laughs] – there is always a feeling of discomfort, “mm, maybe I should have done this slightly different,” because the Ilan Stavans that is sitting with you is not the Ilan Stavans of a year ago, who had the text and was reacting to life in a particular way.

A text is finished the moment the text reaches the page. There is always the temptation to retouch it. There is always the sense, in my view, that one should move forward, and what you did then is an expression of that time, and you should do other projects.

In the introduction you mention that Rulfo’s Mexican Spanish includes countless peasantisms, and that it would seem very jarring if you tried to mimic them in this era. Why did you not include them and what made them so jarring?

It is jarring because… let me transpose it just for a second into the slice of a culture that I think you will understand better. If I tried to translate a rap song from English into Spanish, I will find very quickly that there is no easy referent to the exact same culture in the Spanish speaking world, and that slang in one culture works in one way that doesn’t work in others. If I use the word “chota” in Spanish to describe police, there is no word in English that will make me convey the sense of fear of the degradation, of abuse, of disgust that chota has. “Cops” doesn’t quite work…

Pigs?

But that already brings an animalistic view here that you don’t have in Spanish. So, slang or speech that connects particularly with a region, localisms, or with a class, are very difficult to convey and you don’t want to have the wrong impression. It would have been very easy to use, for instance, language of farmers in the Midwest to recreate certain words that the peasants in Mexico in the 1950s are using. But if I had done that, what people would have thought in those words would be to connect it with Midwest America. The context would have totally been destroyed. And so you have to sometimes sacrifice geographical or cultural contexts in order to creatively convey the content of a word. You can translate words, but culture does not easily translate.

In most of those cases, would you keep the original Spanish, instead of using the jarring word?

I would keep the Spanish because I felt that the Spanish was no longer foreign. Take the word campesino. Campesino is a word that, in 1967, for Schade, might have meant “peasant”. But today if you say campesino, it is clearly a term that is used in certain parts of Mexico and Central America to denote somebody who is illiterate, who has no access to power, who has been alienated from urban society, for decades and decades. “Peasant” has a very different connotation. The word patrón is probably even a better example. Patrón could be simply “boss,” or “leader.” But the word patrón in Spanish means really… when you use “no patrón,” you really mean you are inferior to the person you are connected to. Inferior not only in a momentary way, but in terms of class, in terms of humanity, you consider yourself below that other individual. It is very difficult to look for an equivalent to patrón. And yet, the word patrón is so established that I chose to leave it in several places, because I believe that the English language readers have been exposed to it for long enough to react to it, to get the sensibility.

Reading your translation of “Luvina,” you use the poetic phrase “rumor of wind.” I read The Burning Plain to see how Schade took it – “noise” – and clearly you see this as an issue of translation.

I can tell you in general that the choice had to do with the fact that I wanted to recreate the poetry of the original, el rumor del aire, and simply “noise” wouldn’t have done it. Even though it is less clear in English, the poetry in Spanish is unavoidable.

And if you see the title… I’ll tell you. The title in Spanish has the alliteration – El Llano en Llamas. Llano. Llamas. In English, the first translation was The Burning Plain, which is so dull, so plain, so uninteresting. I immediately said I’ll do it, but it has to be The Plain in Flames, which plays with the alliteration. The Juan Rulfo Foundation said “we love it.” The publisher said “we can’t do it” – because people have already connected The Burning Plain with Rulfo, and if you change the title, you can lose readers. And I said I’m not doing that. If we don’t have “The Plain in Flames,” I won’t do it. And finally we were able to convince them. So they resisted for marketing reasons. That’s something that translators often have to deal with.

I noticed in The Burning Plain, the titles of the stories are extremely different – “No Dogs Bark” as opposed to “You Don’t Hear Dogs Barking” in your translation – which is striking.

The Spanish title – “¿No oyes ladrar los perros?” “You don’t hear the dogs bark.” That was a perfect story! The Spanish is so challenging. You see, in Spanish, it could mean it doesn’t have a question mark. But it could almost implicitly suggest that there is a question there. “Don’t you hear the dogs barking?” And this is the story of a father who is carrying his son… it’s an astonishing story, my God, that enough would have given Rulfo a place in the history of literary classics…The father is taking the son [who is wounded]. The father really doesn’t want to take the son because he is so ambivalent at the life the son has led. He believes that the son actually killed the mother because of his behavior. But he has to take him. The son is covering his ears, and he can’t hear for that reason, and the son is supposed to be the one that would hear the dogs barking when they approach the town where they will find the doctor. But you have the impression that the father might be walking in circles, to prolong the agony. And so it could be, “Don’t you hear the dogs barking?” “You don’t hear the dogs barking.”

I would send my translation to Harold [Augenbraum, co-translator], and he would say, “are you sure of this? What has Schade done? What other options do we have here?” We would have five or six options and I would go back to my original one, try to defend it, until we finally had the one that worked best.

In the story, the father still carries the son. And the father takes some joy, I think, about making his son cry about his mother.

I have to tell you of an experience that transformed my life. Last November [2012] when the book came out, I got an invitation from a high-security prison in upstate New York. The inmates were all reading, in a class, The Plain in Flames. They wanted me to come and talk about the translation. I have never had such a rapt, passionate audience, and we spent a long time discussing that particular story. It has been said that no one understands Hamlet better than a person who has committed a crime, who has actually murdered. And in this particular case, I can tell you that this, between twenty-five and sixty year olds, all of them criminals in one way or another reading the story, transformed my way of seeing the story. They had either the burden of having killed someone, or understood that condition… and they felt the ambivalence of the father’s duty in a way that I had never seen before. It’s as if the story had been written for them.

I see immense differences in the design in both translations. First, with the illustrations and the very stylized text for the story titles in The Burning Plain. One of Rulfo’s photographs graces the cover of The Plain in Flames, and it strikes me as being very similar to his writing, as you say “realismo crudo,” interested with the rawness of life. The Burning Plain almost looks like a collection of fairy tales because of this sort of design. Did you have any say in the use of font, whether or not there would be illustrations, or any other matters of design?

I admire Rulfo as a writer without reservations, even though not everything that he wrote is superb and supreme, enough of it is to put him, in my view, in that shelf of classics that ought to be read for generations. I admire him not in equal measure, but almost, as a photographer as well. His photographs, when you see them, you will realize, are about those silences, and about that sense of desolation and isolation that exists in the Mexican countryside.

I wanted, and thus I petitioned to the Juan Rulfo Foundation, to use more than one photograph, and to see if one or two, or maybe more, could be used in the interior. They told us right away no, and you can only use one on the cover. I was at first disappointed – I thought it would be beautiful for the reader to see the photographs in connection with the book, because this a visual window, by the author himself, to his own stories, unfiltered, untarnished by a translator. Photography doesn’t have a translation, it comes as you see it. But they denied it, and now I think that I am grateful that they did, because the stories are read as stories, and that’s the way Rulfo wrote them. He did not write them to be accompanied by the photographs – they are published in separate volumes.

I am thrilled that I chose the one on the cover. If I have a reservation – and my editor and I claim that reservation – it’s that the font is a little too small. I wish it was a little larger, but I did not have any control on how the book was designed in its interior. I like the spareness, the big spaces of white; I like that we didn’t have any folksy type of imagery. But the stories live or die on their own merit. The same thing is true for the translation.

The complaint that I have about the font has to do with my aging. When I was younger I could read this in an easier way. Now I still can but I can perfectly sympathize with somebody who would say, “Oh, I’m sure those are great stories but the font is too small and I can’t read them.” And I think they should be accessible also to readers who might have that challenge.

I want to ask how that makes you feel as a writer and a translator. The design of the book has an immense impact on your reading. With The Burning Plain, the book itself is such an odd shape…

You have to think, also, in the 1960’s, Latin America was seen as a factory of folklore, much more connected to that kind of mythical past than the United States, which was already moving so fast into a post-capitalist stage of society. So, this style, this design of The Burning Plain reflects the way publishers and translators were looking at Latin America in that period, and here, with The Plain in Flames, I’m happy to say that, if this is a reflection of how we see it, Latin Americans have become contemporaries with the rest of the world, and we don’t need to turn it into folk stories – we can read them as legitimate, authentic, wonderful stories the way we would read them from an author from Russia or from Italy or Egypt or any other part of the world.

I grew up in Mexico and I came at age twenty-five to the United States. It was much easier for me to translate from English into Spanish, because Spanish was a language in which I had grown up in. English is my fourth language. And so it took me years to feel comfortable in English. I have reached a certain point in my life, linguistically, that there is a symmetry between the comfort that I have in Spanish and the comfort that I have in English. For that reason, if the same invitation by an editor had come to me fifteen years ago, when Spanish was much more a powerful force in my linguistic life and English was coming second, I would have had to say no, I don’t think I’m capable of translating Rulfo into English. In 2011, this symmetry was such that I thought I could do a service to Rulfo, that probably somebody who is a native English language speaker cannot do, because for me now the two languages are balanced.

Did that symmetry with English and Spanish come in any way from reading English literature?

It comes from literally having my life cut in two. Half of my life was spent outside the United States, and half of my life now has been spent within the United States, meaning I’ve lived my life inside and outside of English. And after twenty-five years the language becomes you, and you become the language. It comes from reading, it comes from being exposed to the language, it comes from becoming that culture – I am now an American, and a Mexican… I don’t know which is which.

What was your favorite story to translate? And which is your favorite story to read?

“It’s Because We’re So Poor,” the first one that I translated, it’s the story of a boy who is sitting next to his sister and their cow is carried away by the flooded river and he’s describing how their world has collapsed and how the reputation of the family is now in question… I adore that story. I adore “You Don’t Hear Dogs Barking.” If I had to choose ten stories from any writer and do an anthology for the future where only these ten stories would be read… that story would be there.

This is the moment to say that a good short story writer has ten, fifteen, maybe less, five stories to write, and that he or she spends his or her time trying to find which of those stories are going to be final… and many of them are exercises. Many of them are rehearsals for the big crime that will be committed in the defining story. I think some of the stories come as preparations for the great stories that you have in the book. But even a not-fully-developed story by Rulfo is an incredible story.

I am in the minority in not thinking that Pedro Paramo is a better book than this. There are many who think that Pedro Paramo is his greatest contribution. I believe El Llano en Llamas is the greatest contribution. I think some stories here are eternal.