Today was the last meeting for a Tuesday-Thursday comp class that has been, or maybe I can now say had been, a fucking grind.

One bright spot was a student professing an interest in film. A few weeks ago he told me about watching Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925), and asked for recommendations. I rattled off titles, unsure how soaked he (and by extent, all) younger persons might be in (my notions of) the contemporary film canon. There are so many options now competing for eyeballs and earholes. We didn’t all grow up with our dad finishing a third beer and then insisting we stay up too late on a Sunday to catch the second half of For a Few Dollars More on the superstation. I suggested he work at checking off AFI’s “100 Years” list like I did back in circa 1998. “If something yanks at you, watch it again.”

But the kid wanted something stranger, and he followed up today. I rattled off titles, told him to email me, I’d send him a list, which he did, and then I did, send him a list that is — which was fun for me — and then I realized that I should really point him to film critic Scott Tobias’s series The New Cult Canon.

Back when the internet was still pretty good, Tobias wrote weekly column on a film he dared to place in his “New Cult Canon” — a continuation of film critic Danny Peary’s Cult Movies books. Tobias’s series ran at The AV Club (during the site’s glory years before capitalist hacks gutted it). Tobias’s New Cult Canon project intersected with an apparent wider access to films, whether it was your local library’s extensive DVD collection, Netflix sending you a disc through the USPS, or, y’know, internet piracy. Offbeat was now on the path, if you knew where to tread.

So for a few years, The New Cult Canon was a bit of a touchstone for me. It offered leads to new film experiences, made me revisit films I’d seen with an uncritical eye in the past through a new lens, and even aggravated with endorsements that I could never agree with. I loved The New Cult Canon column, and I was happy when Tobias revived it a few years ago on The Reveal.

But back to where I started, with the kid who wanted some film recommendations, wanted to immerse himself over the winter break (I’m pretty sure he used the verb immerse) — I didn’t follow up with an email to this link on IMDB of Tobias’s The New Cult Canon, which I’d to found to share with the kid who wanted some film recommendations–I started this blog instead.

As of now, there are 176 entries in The New Cult Canon. The first 162 were part of the series; original run at the AV Club. Coming across the original list this evening made me want to revisit the films, catch some of the ones I didn’t find or make time for before, and generally, like share.

The current media environment seems primed for ready-made cult movies. Film like, say, Late Night with the Devil (Cairnes, 2023) or Possessor (B. Cronenberg, 2020) are fun and compelling — but they also fit neatly into a specific market niche. (Where is the dad three beers deep who compels his youngan to stick it out with the second half of Under the Silver Lake (Mitchell, 2018)?

(If I review the previous paragraph, which I won’t, I’ll conclude I’m spoiled. Long live weird films.)

So let’s go:

Links on titles go to Tobias’s original write-ups. (I’d love to see a book of these.)

Arbitrary 0-10 score, based on How I Am Feeling At This Particular Moment.

The Alternate isn’t offered as a superior or inferior recommendation, just an alternate (unless it is offered as such).

I love Donnie Darko. I can’t remember how I first came across it, but I had the DVD and I would make people watch it. This kind of thing is maybe embarrassing to admit now; I think Donnie Darko hit a bad revisionist patch. Especially after Southland Tales and The Box.

When the director’s cut was released in theaters, sometime around 2005, I made some friends watch it with me in the theater. They fucking hated it.

I watched it with my son earlier this year and it was not nearly as weird as I’d remembered it and he enjoyed it and so did I. He got the E.T. reference and thought Patrick Swayze was a total creep.

8.5/10

Alternate: Southland Tales, Richard Kelly, 2006. (Look for the Cannes cut online.)

2. Morvern Callar, Lynne Ramsay, 2002

I knew about Morvern Callar because of its soundtrack (which was a totally legitimate way to know about a film two or three decades ago). I didn’t search Lynne Ramsay’s film out until after Tobias’s review.

This film made my stomach hurt and I never want to see it again. (Not a negative criticism.)

I feel the same way about the other two Ramsay films I’ve seen, We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and You Were Never Really Here (2017).

6.5/10

Alternate: You Were Never Really Here, Lynne Ramsay, 2017.

3. Irma Vep, Olivier Assayas, 1996

Minor fun, very French, ultimately ephemeral.

6/10

Alternate: Irma Vep, Olivier Assays, 2022 — an eight-episode HBO miniseries.

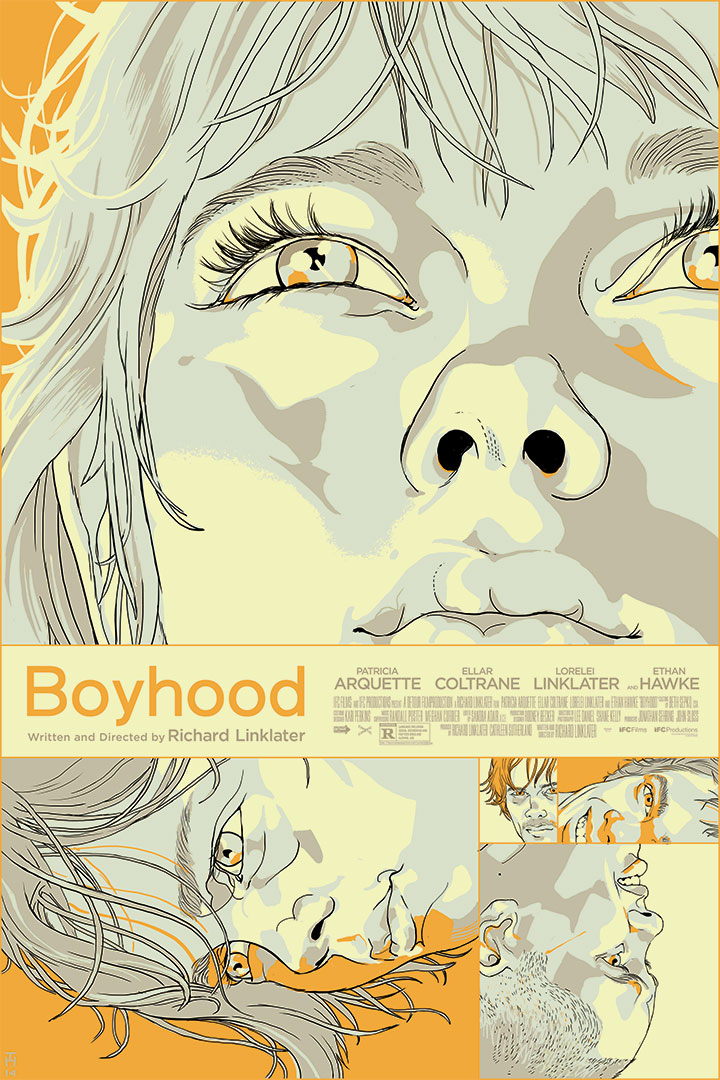

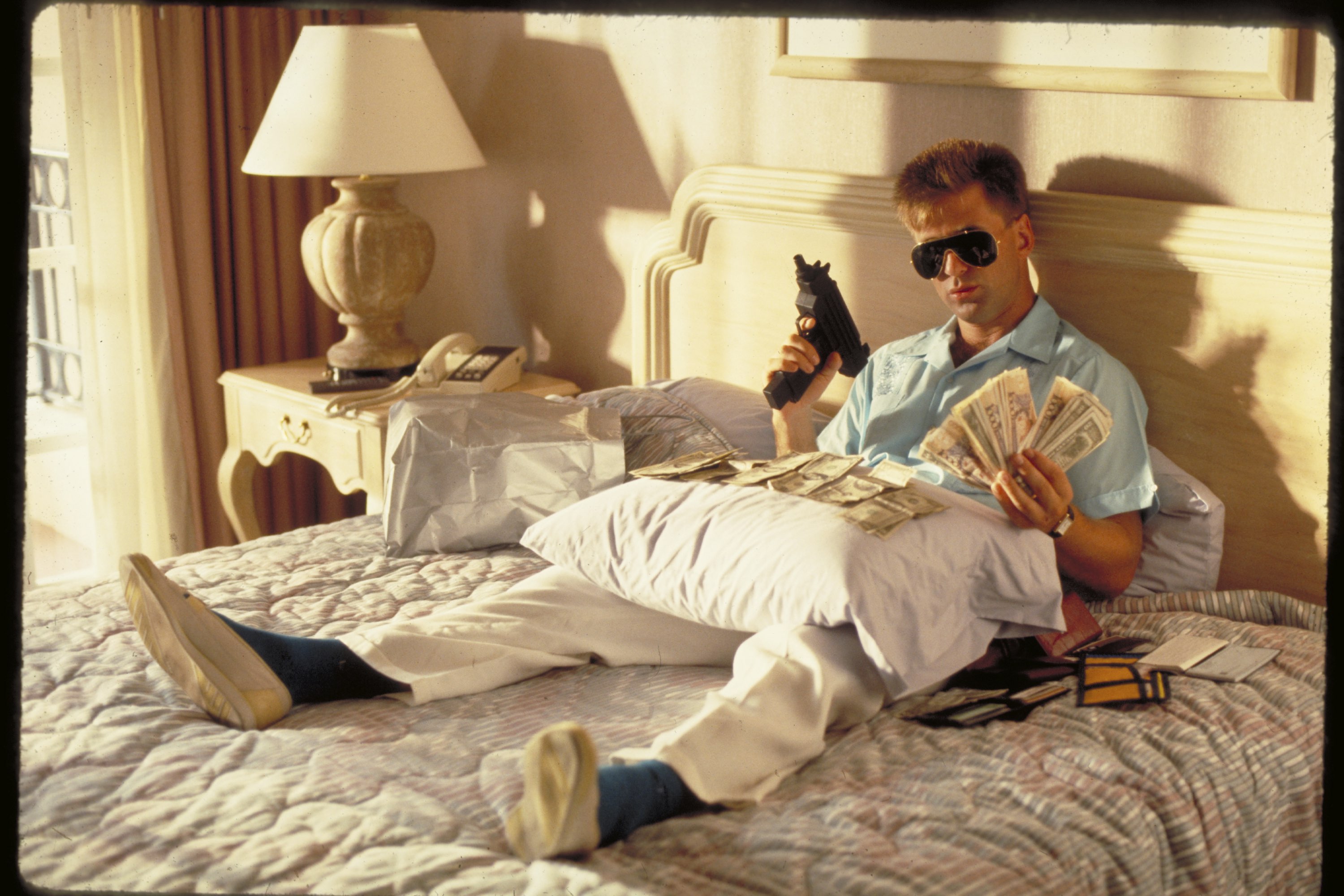

4. Miami Blues, George Armitage, 1990

Miami Blues is a very strange film. Except that it’s not strange: it’s a tonally-coherent, self-contained, “pastel-colored neo-noir,” as Tobias writes—but it feels like it comes from a different world. Alec Baldwin and Jennifer Jason Leigh seem, I dunno—skinnier? Is skinnier the right word?—here. The thickness of fame doesn’t stick to them so heavily. Miami Blues is fun but also mean-spirited, vicious even. It’s also the first entry on here that I would never have watched had it not been on Tobias’s recommendation.

7.5/10

Alternate: Grosse Pointe Blank, George Armitage, 1997

5. Babe: Pig in the City, George Miller, 1998

“Yeah, she thinks she’s Babe: Pig in the City.“

A perfect film.

10/10

Alternate: The Road Warrior, George Miller, 1981

6. They Live, John Carpenter, 1988

Another perfect movie, and one that only gets better with the years, through no fault of its own. They Live was certainly on the list I emailed the student. Roddy Piper (a rowdy man, by some accounts), also starred in Hell Comes to Frogtown (Donald G. Jackson and RJ Kizer, 1988) the same year, a very bad film, but also maybe a cult film.

10/10

Alternate: Like literally any John Carpenter film.

I hate and have always hated Clerks and every other Kevin Smith film I’ve seen. I remember renting it from Blockbuster my junior year of high school because of some stupid fucking write up in Spin or Rolling Stone and thinking it was bad cold garbage, not even warm garbage — poorly-shot, poorly-acted, unfunny. Even at (especially at?j sixteen, Smith’s vision of reality struck me as emotionally-stunted, stupid, etiolated, and even worse, dreadfully boring. I remember sitting through Chasing Amy and Dogma in communal settings, thinking, What the fuck is this cold, cold garbage?

But Tobias’s inclusion of Smith’s bad awful retrograde shit makes sense — Clerks spoke to a significant subset in the nineties, no matter how bad the film sucks.

0.5/10

Alternate: As Smith has never made an interesting film, let alone a good one, my instinct is to go to Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1990) — but that shows up later in the New Cult Canon. So, I dunno–a better film about friends and problematic weirdos: Ghost World, Terry Zwigoff, 2001

8. Primer, Shane Carruth (2004)

Let’s not end on a sour note.

I think that it was Tobias’s New Cult Canon series that hipped me to Primer, Shane Carruth’s brilliant lo-fi take on time travel. Carruth made the film for under ten grand, but it looks great and is very smart, and most of all, trusts its audience by throwing them into the deep end. (Primer is perhaps the inverse of Clerks. I hate that sentence, but I won’t delete it. They don’t belong in the same universe, these films; Primer builds its time machine out there!)

10/10

Alternate: Upstream Color, Shane Carruth, 2013