The titular figure in Heinrich Böll’s 1963 novel The Clown is Hans Schnier, a man whose personal and professional life is burning down around him as he howls in (often hilarious) despair. During a performance at a third-rate venue, Hans purposefully injures his knee and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) as he reflects on his past.

The titular figure in Heinrich Böll’s 1963 novel The Clown is Hans Schnier, a man whose personal and professional life is burning down around him as he howls in (often hilarious) despair. During a performance at a third-rate venue, Hans purposefully injures his knee and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) as he reflects on his past.

His common-law wife Marie has returned to the conservative Catholicism she was raised on, and subsequently left Hans; even worse, shes’ taken up with a bourgeois hack named Zupfner. Marie and Hans initially came together as teens, sexing it up in their provincial German town. After scandalizing all the decent ex-Nazis in town, they retreat to the comparatively cosmopolitan city of Bonn and begin a life (in sin) together, traveling from venue to venue and performance to performance as Hans’s career grows.

It becomes clear through the course of The Clown — which is essentially Hans’s long, angry rant against complacent conformity — that Marie is merely an object for Hans, a romantic idealization. He repeatedly tells us that she doesn’t get his art–

I don’t believe there is anyone in the world who understands a clown, even one clown doesn’t understand another, envy and jealousy always enter into it. Marie came close to understanding me, but she never quite understood me. She always felt that as a “creative person” I must be “deeply interested in absorbing as much culture as possible.” She was wrong.

Hans is always the outsider, even to the woman he loves. Still, Marie represents both comfort and some sense of continuity for this traveling artist whose life is basically a series of hotels, train rides, and performances. Without her, Hans is lost, adrift without an anchor, pure vitriol aimed at a society he rebukes at every turn. Consider his parents, for instance, rich Protestants with a penchant for providing patronage to middling writers — Hans’s hate for them is almost metaphorical, a hate that extends to their religion and their complicity in the evils of WWII. While The Clown is a highly personal story, the tale of an artistic soul tortured in the absence of his love, it’s also an indictment of postwar Germany, a milieu all-too ready to whitewash its sins in the easy absolution of cheap religion.

At times the nuances of The Clown’s argument against the conformist postwar German culture were lost on me. Hans’s many references to the particular rhythms and contrasts of Teutonic Protestants and Catholics were beyond my ken. Still, this rarely detracted from my enjoyment or involvement in the novel. Its caustic bite and extreme depression is tempered by ironic humor and expansive knowledge. Here’s an early passage in the book that I think shows off these attributes and obsessions while highlighting a bizarre metaphysical conceit that I don’t know how to properly work into this review–

I felt sick. I forgot to say that not only do I suffer from depression and headaches but a I also have another, almost mystical peculiarity: I can detect smells over the telephone. . . . I had to get up and clean my teeth. Then I gargled with some of the cognac that was left, laboriously removed my makeup, got into bed again, and thought of Marie, of Christians, of Catholics, and contemplated the future. I thought of the gutters I would lie in one day. For a clown approaching fifty there are only two alternatives: gutter or palace. I had no faith in the palace, and before reaching fifty I had somehow to get through another twenty-two years.

So we learn that our hero is only in his late twenties, yet already romanticizes a dramatic life of failure; he sees himself as the failed artist down in the gutter, perhaps dreaming of the stars. And he can smell through the phone!

At its core, The Clown is a searing attack on hypocrisy, one grounded in a sense of time and place. And it’s this grounding that gives the book the weight — the concreteness of truth — to transcend its postwar setting and remain relevant today in a world where language, religion, and custom all provide societies and their institutions a kind of metaphysical escape hatch to avoid squarely assessing the gaps between mantra and action. Hans shows us that it takes a jester to truthfully comment on the absurdity of modernity; it’s the trickster whose pantomimes tap into the most mundane gestures to expose the intricate ways these gestures might disguise ugly, banal, or even evil intentions. Great stuff.

The Clown is new in print again from Melville House.

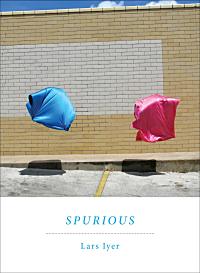

I shouldn’t be reading five novels at once. It’s a terrible idea, a symptom of a bad habit that I thought I’d broken, but after abandoning Levin’s tedious tome

I shouldn’t be reading five novels at once. It’s a terrible idea, a symptom of a bad habit that I thought I’d broken, but after abandoning Levin’s tedious tome  Iyer’s book dovetails nicely with W.G. Sebald’s first novel, Vertigo, which I picked up expressly to get the bad taste of Shteyngart out of my brain. Both books are haunted by Kafka, both blur the lines between fiction and biography, both are works of and about flânerie, and both are melancholy. The book comprises four sections; the first section tells the story of the romantic novelist Stendhal (or, more to the point, a version of Stendhal); the second section details two trips Sebald made to Italy, one in 1980, and one in 1987; the third

Iyer’s book dovetails nicely with W.G. Sebald’s first novel, Vertigo, which I picked up expressly to get the bad taste of Shteyngart out of my brain. Both books are haunted by Kafka, both blur the lines between fiction and biography, both are works of and about flânerie, and both are melancholy. The book comprises four sections; the first section tells the story of the romantic novelist Stendhal (or, more to the point, a version of Stendhal); the second section details two trips Sebald made to Italy, one in 1980, and one in 1987; the third  section, which I just read last night, describes a trip Kakfa took to Italy near the end of his life. I’m almost certain that I’ve read this section, “Dr. K Takes the Waters at Riva,” before — but I can’t remember where or when. It was strange reading it, almost as if I were experiencing some of the vertigo that permeates the volume. Full review forthcoming.

section, which I just read last night, describes a trip Kakfa took to Italy near the end of his life. I’m almost certain that I’ve read this section, “Dr. K Takes the Waters at Riva,” before — but I can’t remember where or when. It was strange reading it, almost as if I were experiencing some of the vertigo that permeates the volume. Full review forthcoming. Continuing in this Teutonic vein is Heinrich Böll’s novel The Clown (also Melville House). It’s postwar Germany, and Hans Schnier is a clown who’s crashing and burning. He hurts himself–purposefully–during a performance (at one of the increasingly more provincial venues he finds himself playing for these days) and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) and reflects on his past. What’s eating him up? His gal Marie, basically his common-law wife, has reverted back to her Catholic ways and up and left him for some chump named Zupfner. Schnier rants against a complacent and complicit German bourgeoisie, spitting vitriol against Protestants and Catholics alike; some of the best parts of the novel though are his ravings about art and the role of the “artiste” in society. Also: he can smell over the phone. Full review soon.

Continuing in this Teutonic vein is Heinrich Böll’s novel The Clown (also Melville House). It’s postwar Germany, and Hans Schnier is a clown who’s crashing and burning. He hurts himself–purposefully–during a performance (at one of the increasingly more provincial venues he finds himself playing for these days) and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) and reflects on his past. What’s eating him up? His gal Marie, basically his common-law wife, has reverted back to her Catholic ways and up and left him for some chump named Zupfner. Schnier rants against a complacent and complicit German bourgeoisie, spitting vitriol against Protestants and Catholics alike; some of the best parts of the novel though are his ravings about art and the role of the “artiste” in society. Also: he can smell over the phone. Full review soon. Wesley Stace’s new novel Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (new from Picador) is a musical murder mystery set in the early part of 20th century Britain. Our (seemingly less than reliable) narrator Leslie Shepherd is a music critic with an aristocratic background who likes to spend his weekends collecting folk songs with other rich boys in the towns surrounding their country manors. He’s smitten (platonically, of course) with Charles Jessold, a middle class composer with a spark of avant-garde genius, and wins the younger man’s friendship quickly when he tells the story of Carlo Gesualdo, a fifteenth century composer/lord who kills his wife and her lover. (Notice the etymological connection between their names?) This tale of murder and cuckoldry is doubled in the ballad “

Wesley Stace’s new novel Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (new from Picador) is a musical murder mystery set in the early part of 20th century Britain. Our (seemingly less than reliable) narrator Leslie Shepherd is a music critic with an aristocratic background who likes to spend his weekends collecting folk songs with other rich boys in the towns surrounding their country manors. He’s smitten (platonically, of course) with Charles Jessold, a middle class composer with a spark of avant-garde genius, and wins the younger man’s friendship quickly when he tells the story of Carlo Gesualdo, a fifteenth century composer/lord who kills his wife and her lover. (Notice the etymological connection between their names?) This tale of murder and cuckoldry is doubled in the ballad “