Does [the novel’s] ironic tone (which often feels like a reflex, a tic) preclude sincerity? Is all this talk of community no more than an artful confection, the purest kind of cynicism? The question is impossible to resolve, so each of these episodes — and indeed the book as a whole — takes on a sort of hermetic undecidability.

Ryan Chang: Hey man, I just skimmed the NYT review—per the excerpt you provided—because I don’t want Kunzru clouding any of my response. It’s certainly a question I too grapple with, and I think Kunzru is right insofar that the question is “undecidable” but not for the reason(s) he suggests. I agree with you that he dodges the question, whether or not from editorial pressure or a reticence to actually address “hermetic undecidability.”

For one, I’m not sure myself if The Author ever arrives at the Whitmanic model of democracy he posits. I’m also not sure if he is supposed to “arrive” in the sense that a finality is set. I guess I also want to riff a bit on how finality might be described. Is finality then something static; as in, somehow 10:04 transmits–electrocutes, reverberates–through its readership, now coeval (the when negligent, the position of the reader enmeshed in the text is the same at 10 PM here as it is at 5 AM there), the novel’s theses and everything is suddenly Whitmanic? Community successfully reimagined and cemented? That sounds too easy, too convenient, too short-sighted. Or is it a kind of arrival into an embodiment of time that exists outside of conventional literary clocks, which is also a Market-based clock — it’s my sense that the kind of democracy Whitman envisions in his work is one constantly in flux, a “reality in process” and thus in opposition to the capitalist clock? That is, we know we are supposed to “stop” working at 5, the embodiment of the currency-based clock disappears after 5, but it’s a contrasting relationship. Our time outside of the currency then absorbs a negative value (I think The Author only mentions once or twice how we are all connected by our debt, a negativity projected into the future), though the illusion of the clock is that we are “free” in our time. OK: in a literary sense, wouldn’t this be a sense of a text’s world stopping, a suspension that retroactively pauses the whole book? That 10:04 ends not only with a dissolution of prose into poetry, but also The Author into Whitman and thus recasting the first-/third-person narrator into a lyric-poet mode suggests the book’s integration into our, the reader’s, time (and also, retroactively, the entirety of the text). In that sense, for me, the issue whether or not The Author of 10:04 integrates the book fully into a Whitmanic model is not necessarily the point — it is that he, and also we hopefully through him — actively participate in remaking a “bad form of collectivity” less so.

I can’t argue that 10:04 is itself an exercise in “stylized despair,” but it is not only despair in which the text traffics. You say the “bad forms of collectivity our narrator is forced to partake in” — yes, he is forced, and think the ennui you read in him is part of the point. The arc of this book reminds me of the Rilke quote I posted a while ago, the one that starts with “I am learning to see.” I suppose, for The Author, he is learning to re-see: not only with Marxist glasses (labor relations, debt, etc). but also what energies Marx transmogrified into Whitman might reinvest in bad collective forms. The line “modernist resistance to the market” suggested a kind of surrender to the failure of the conservatism the great Difficult Modern Poets (Pound is one that easily comes to mind) developed in their work as a political project, a moment of re-conceptualization of his own political project. What The Author holds onto is that collective; I guess this leads me to a question about your reading of Whitman — do you not read in him a sense that inherent contradiction is not only a) the fabric, weaves and quilts of the American subject (and I cringe to use this metaphor, but it is himself who uses it) and thus b) integral to Whitman’s politics? I also want to say that the optimism of Whitman has always been sentimental for me. It also seems that Whitman is OK with being a capitalist, whereas The Author of 10:04 is not, at least not in his America. Perhaps we can use Marx to better color in Whitman’s collectivism. In Democratic Vistas, Whitman says, “…[The] fear of conflicting and irreconcilable interiors, and the lack of a common skeleton, knitting all close, continually haunts.” Knitting all close — I love this miserly image of the selfish hoarder, of making her own shawl for only herself. There’s nothing American about this for Whitman (and in many ways this has totally happened.) The “lack of a common skeleton,” too, is a lack of a collectivity. 20th-C. Communism, among several travesties and tragedies, stripped agency from the “I” in an effort to curb capitalistic greed. Late capitalism gives the “I” so much power (ostensibly, Marx would, of course, go to task, but I guess the ideological reality of Capitalism would say that the “I” is everything and everything) that she’s “knitting all close” to these other “I”‘s with no sense of skeletal inclusion. Whitman wants Marx without any cost to the American Individual which, to me, is an utterly naïve, steroidal utopia. If the body is the metaphor Whitman chooses, he disregards that the body is not totally bonded to the mind. As I type that now I think perhaps this is why The Author is diagnosed with Marfan syndrome. This illness, this daily reminder that he’s not only an intellectual being but a fragile and material thing drives him to try and connect, à la Whitman, with the world around him. I think The Author recognizes that he can’t do much on his own, that he needs us, he needs us to build that Whitmanic skeleton. That bad form of collectivity is what we have now, and what we may always have, and it’s that struggle to make it better that’s important to The Author.

Blah, long-winded. I hope these were English sentences. I did want to ask you, though, shortly after our last exchange, about the child-with-Alex/Roberto story line, but I wanted to wait until you’d finished the book. What did you think? I thought that Back To The Future did more than set up the temporal structure of the book, it sort of regressed The Author into a childhood. I mean, BTTF is this “crucial” movie to him in his youth; the first-/third-person narrator travels back in time (though not as far/deep) through the text; he engages with Roberto who is the age of the narrator when he watched BTTF. I want to say that within Whitman there is a kind of regression, too, back into a notion of the pure unadulterated enthusiasm of children. Coupled with the illness, the “bad form of collectivity” (ie., a “co-construction” of a child with Alex, both Father and not), the enrichment of children through Whitman also seemed to me a Utopian endeavor. Perhaps it’s my generation, my age, my heavy Bernhard-bent, but the notion that a parent — even in this “post-family” unit — could raise/develop/program a child into a better fit for a Whitmanic polity seems ludicrous and selfish on the one hand, but also totally hopeful and optimistic on the other. That writing out what a Whitmanic democracy could do for us isn’t enough, he has to take a risk on realizing that model. I am curious to hear from you if you found any kernel of hope at all in this book. Hope for a present, for a future. And also: the inclusion of Roberto’s book within the text?

ET: Ryan, I finally finished the book, reading the rest of it in two late-night sittings. I ended up enjoying the Marfa section very much, and my enthusiasm for that section carried through to much of the end of the book, despite finding many of its postmodern meta-moves annoying. I liked that the novel ended up being a Comedy—I don’t think I could forgive it a Tragic ending. I was even moved by the final image of the book, where our narrator—who identifies himself as “author” and the we (he refuses to name a we) as “reader”—arrives at a second-person plural pronoun—is that you the author’s attempt at a we? I don’t know. And, as you point out, the rhetorical trick repeats the one that Whitman tries to pull at the end of Song of Myself (“I stop somewhere waiting for you”).

RC: Ed, I’m glad you finally the finished the book; it sounds like the pay-off was somewhat worth the bothersome irony & metatextuality for you.

I agree, I think that final you is an attempt to co-construct the we, between the Reader and The Author, in the same way that Whitman continually projects himself into the future, anticipating that youwho meets him at the end of his poem, as you say, anchored in the imaginative capacity (I like the way you understand WW’s work as a single project, as if it’s always in a state of becoming, which is something I think at work in the Lerner as well — the sense that the book The Author intends to write is instead the book we read instead. The book becomes itself around the narrator). I agree, Whitman’s politics are not inseparable from his idealism (I apologize if my question was confusing), and I think it furthers our shared point that Lerner attempts, in a strange way, to become Whitman by the end of the text (In the Marfa section, note that he is unkempt, has a beard, is in a perpetual situation of loafing (I think of his regular use of “awesome” throughout)).

The anxiety you point to is related to the hope-in-peril you correctly identify in the ending, I think. There’s even more self-consciousness of his privilege which, while not totally redeeming him, still separates The Author against his peers at the literary dinner, who participate in the capitalist-consumerist machine of book publishing. I think the anxiety & self-consciousness is endearing insofar as it’s also a different form of his wariness to assert a position viz. “transfers of identity.” As he notes in that scene, each of his selves, coeval between the I and the You, watch the flickering light on the promenade from their respective present tenses (which act nicely as different angles oriented toward a work of art).

I like your reading of the inclusion of Roberto’s text, not only as a representative of the threat/specter of extinction, of our mortality, but of the possibilities after our mortality and your point that the “narrator has to exist” in writing. To true, metafictional form, The Author, in-text, is able to become truly coeval by including the text that he has co-constructed with Roberto. He inscribes a version of himself inscribed in a text.

To your last point: perhaps it’s in the flashes between the irony and self-reflexion that sincerity can arrive? I’m not sure. I’m hesitant to answer some of these questions because it’s those flashes I intuit in the text that are the most successful communications/communions with the Reader. I also enjoy this space of not knowing–not knowing is a space of possibility, which is what 10:04 is about, for me.

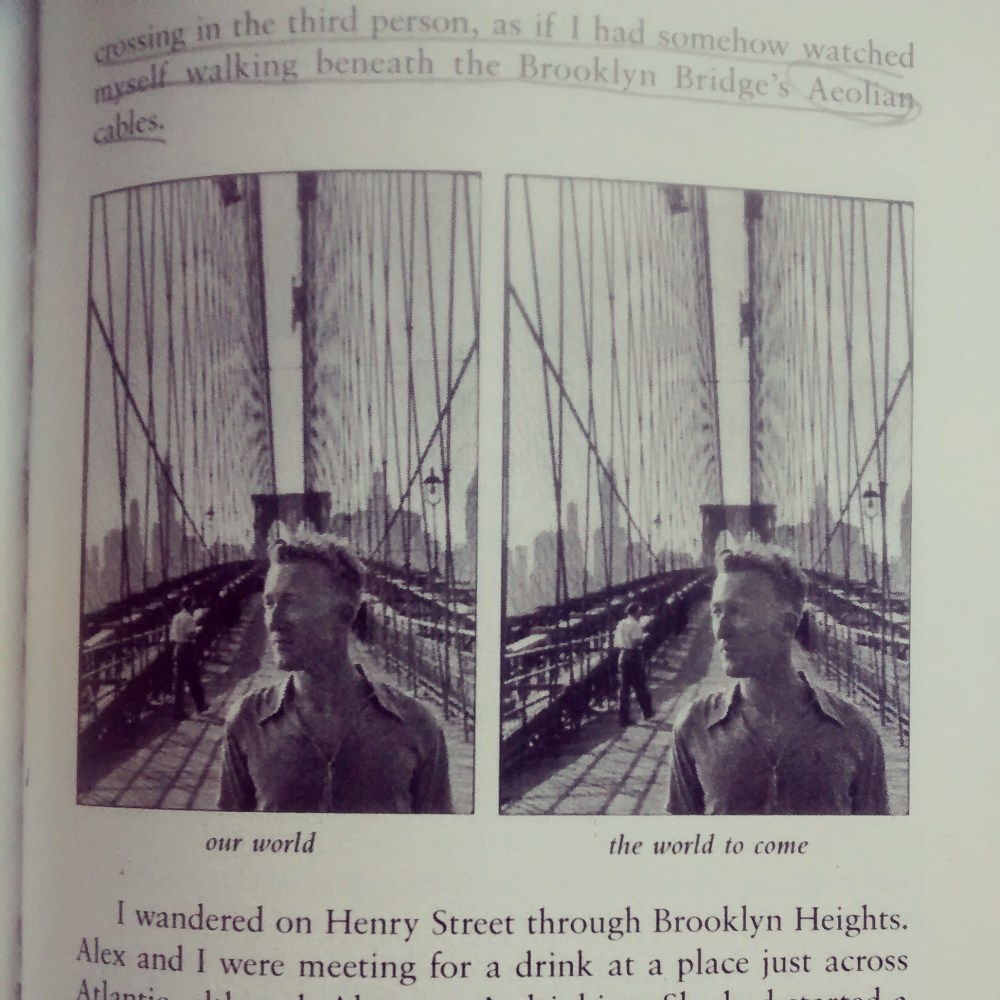

ET: Ryan, your last line about a “space of not knowing” gives me an easy lead in to a last question for you—how did the images in the book affect your reading/interpretation? My digital galley simply said [Illustration TK] whenever an image was to be inserted; it wasn’t until I got to the end of the book (which, in a digital book, I think readers are far less likely to like, flick back to) that I saw a list of image credits, but even then that list wasn’t organized into page numbers or even, I think, the order in which the images are supposed to appear.

RC: Agh, that’s frustrating. They are definitely important. My immediate reaction is: “No! They’re integral to the text!” but that might be because the naive, shallow answer is that the illustrations are illustrative of the text, that they work in tandem. To that end, they did help to concretize the Author’s art criticism essays, to repeat the little Hasidic fable that functions as a kind of epigraph, or prologue.

They did their best job when they tried to force the reader into seeing/reading the same phenomena from different angles or, in Lerner’s analogy, different temporalities, as his Whitmanic project is wont to do. I attached two of the best examples, and one other one that I thought didn’t work so well.

To end with who we started with, the comparison to Sebald is obvious, but I think dead-ended. Again, I think this is just a technique that Sebald did so well it’s become one avenue among many of his that writers will be stealing for a long time. That said, I think Sebald’s use is much more effective, more visceral. I don’t know why, perhaps for the fact that images play a much more integral role in his work than Lerner’s. There’s a greater variance of the size of images (I think in Rings he has that two-page spread), and they actually interrupt the text rather than buttress it, that they operate on the same register of prose. Sebald may be equating the visual to the textual whereas Lerner may be equating the textual to the visual. Does that make any sense at all? It could be the other way around for Sebald and Lerner, but that’s how I’m reading the Lerner.

[…] banaliteit een vorm van cynisme en wil Lerner ontsnappen aan zijn eigen vragen? Dat wordt hier […]

LikeLike

[…] 10:04, Ben Lerner […]

LikeLike

[…] implicitly, whatever other small town, would have to be transposed, if you like, into another key. To mention Lerner again (briefly) — do you remember that scene in the book, with the first hurricane, the […]

LikeLike