They were entering Fairing’s Parish, named after a priest who’d lived topside years ago. During the Depression of the ’30s, in an hour of apocalyptic well-being, he had decided that the rats were going to take over after New York died. Lasting eighteen hours a day, his beat had covered the breadlines and missions, where he gave comfort, stitched up raggedy souls. He foresaw nothing but a city of starved corpses, covering the sidewalks and the grass of the parks, lying belly-up in the fountains, hanging wrynecked from the streetlamps. The city—maybe America, his horizons didn’t extend that far—would belong to the rats before the year was out. This being the case, Father Fairing thought it best for the rats to be given a head start—which meant conversion to the Roman Church. One night early in Roosevelt’s first term, he climbed downstairs through the nearest manhole, bringing a Baltimore Catechism, his breviary and, for reasons nobody found out, a copy of Knight’s Modern Seamanship. The first thing he did, according to his journals (discovered months after he died) was to put an eternal blessing and a few exorcisms on all the water flowing through the sewers between Lexington and the East River and between Eighty-sixth and Seventy-ninth Streets. This was the area which became Fairing’s Parish. These benisons made sure of an adequate supply of holy water; also eliminated the trouble of individual baptisms when he had finally converted all the rats in the parish. Too, he expected other rats to hear what was going on under the upper East Side, and come likewise to be converted. Before long he would be spiritual leader of the inheritors of the earth. He considered it small enough sacrifice on their part to provide three of their own per day for physical sustenance, in return for the spiritual nourishment he was giving them.

Accordingly, he built himself a small shelter on one bank of the sewer. His cassock for a bed, his breviary for a pillow. Each morning he’d make a small fire from driftwood collected and set out to dry the night before. Nearby was a depression in the concrete which sat beneath a downspout for rainwater. Here he drank and washed. After a breakfast of roast rat (“The livers,” he wrote, “are particularly succulent”) he set about his first task: learning to communicate with the rats. Presumably he succeeded. An entry for 23 November 1934 says:

Ignatius is proving a very difficult student indeed. He quarreled with me today over the nature of indulgences. Bartholomew and Teresa supported him. I read them from with me today over the nature of indulgences. Bartholomew and Teresa supported him. I read them from the catechism: “The Church by means of indulgences remits the temporal punishment due to sin by applying to us from her spiritual treasury part of the infinite satisfaction of Jesus Christ and of the superabundant satisfaction of the Blessed Virgin Mary and of the saints.”

“And what,” inquired Ignatius, “is this superabundant satisfaction?”

Again I read: “That which they gained during their lifetime but did not need, and which the Church applies to their fellow members of the communion of saints.”

“Aha,” crowed Ignatius, “then I cannot see how this differs from Marxist communism, which you told us is Godless. To each according to his needs, from each according to his abilities.” I tried to explain that there were different sorts of communism: that the early Church, indeed, was based on a common charity and sharing of goods. Bartholomew chimed in at this point with the observation that perhaps this doctrine of a spiritual treasury arose from the economic and social conditions of the Church in her infancy. Teresa promptly accused Bartholomew of holding Marxist views himself, and a terrible fight broke out, in which poor Teresa had an eye scratched from the socket. To spare her further pain, I put her to sleep and made a delicious meal from her remains, shortly after sext. I have discovered the tails, if boiled long enough, are quite agreeable.

Evidently he converted at least one batch. There is no further mention in the journals of the skeptic Ignatius: perhaps he died in another fight, perhaps he left the community for the pagan reaches of Downtown. After the first conversion the entries begin to taper off: but all are optimistic, at times euphoric. They give a picture of the Parish as a little enclave of light in a howling Dark Age of ignorance and barbarity.

Rat meat didn’t agree with the Father, in the long run. Perhaps there was infection. Perhaps, too, the Marxist tendencies of his flock reminded him too much of what he had seen and heard above ground, on the breadlines, by sick and maternity beds, even in the confessional; and thus the cheerful heart reflected by his late entries was really only a necessary delusion to protect himself from the bleak truth that his pale and sinuous parishioners might turn out no better than the animals whose estate they were succeeding to. His last entry gives a hint of some such feeling:

When Augustine is mayor of the city (for he is a splendid fellow, and the others are devoted to him) will he, or his council, remember an old priest? Not with any sinecure or fat pension, but with true charity in their hearts? For though devotion to God is rewarded in Heaven and just as surely is not rewarded on this earth, some spiritual satisfaction, I trust, will be found in the New City whose foundations we lay here, in this Iona beneath the old foundations. If it cannot be, I shall nevertheless go to peace, at one with God. Of course that is the best reward. I have been the classical Old Priest—never particularly robust, never affluent—most of my life. Perhaps

The journal ends here. It is still preserved in an inaccessible region of the Vatican library, and in the minds of the few old-timers in the New York Sewer Department who got to see it when it was discovered. It lay on top of a brick, stone and stick cairn large enough to cover a human corpse, assembled in a stretch of 36-inch pipe near a frontier of the Parish. Next to it lay the breviary. There was no trace of the catechism or Knight’s Modern Seamanship.

“Maybe,” said Zeitsuss’s predecessor Manfred Katz after reading the journal, “maybe they are studying the best way to leave a sinking ship.”

The stories, by the time Profane heard them, were pretty much apocryphal and more fantasy than the record itself warranted. At no point in the twenty or so years the legend had been handed on did it occur to anyone to question the old priest’s sanity. It is this way with sewer stories. They just are. Truth or falsity don’t apply.

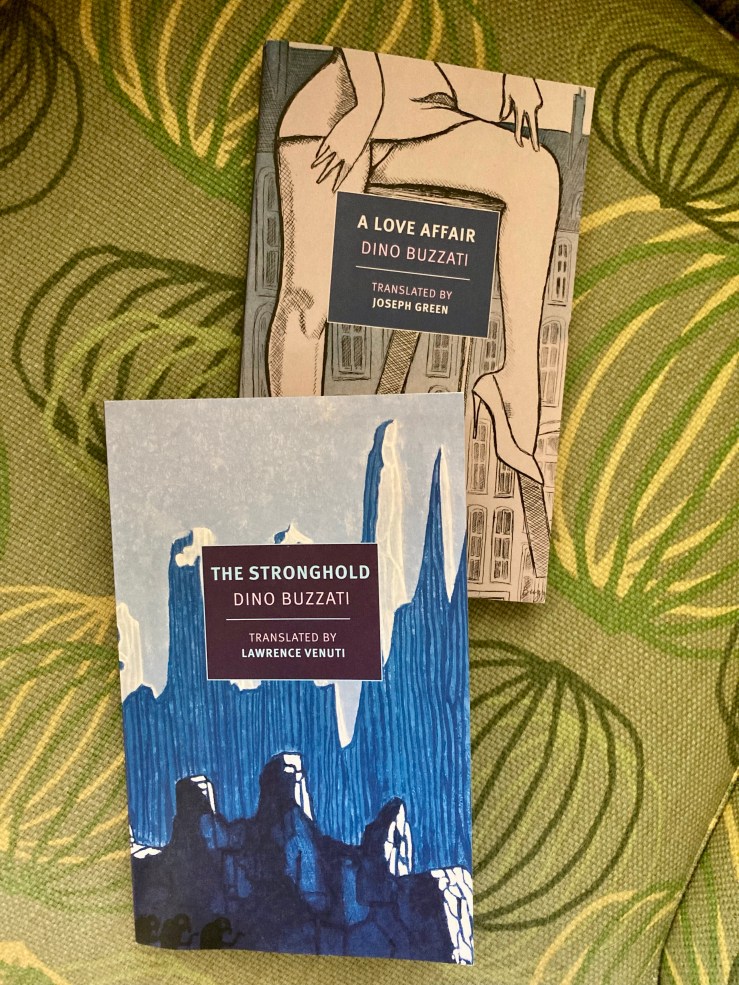

From Thomas Pynchon’s 1963 novel V.