Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Chapter 21:

We move from trans-Atlantic passage to Central Europe pretty quickly. Hicks’s spy handlers Alf and Pip (and like at this point I don’t think he fully realizes Alf and Pip are his handlers on whatever shadow ticket he’s picked up) — Hicks’s spy handlers Alf and Pip leave Hicks on the train while they depart into Belgrade, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

In the Quarrenders’ place emerges Egon Praediger, claiming to be of ICPC — the International Criminal Police Commission (not the Insane Clown Posse Crew), progenitor of Interpol (not the dour 2000s band, but the ICPO). Egon produces “a jarful of cocaine crystals” and grinds up some fat lines — “a routine known around Chicago as ‘hitching up the reindeer,'” the narrator informs us. While ingesting the coke, Egon eventually discloses the shadow ticket Hicks is working: “as you pursue the elusive Miss Airmont, we keep the shadow on you day and night, hoping that Bruno at a moment of diminished attention will make some fateful lunge.” (In another nod to Shadow Ticket’s Gothic motif, the narrator tells us that Egon pronounces the name Bruno Airmont “the way Dracula pronounces the name Van Helsing”).

It turns out that the Al Capone of cheese is the ICPC’s “most sought-after public enemy,” wanted for “criminal activities including murder, tax evasion in a number of countries, [and] Cheese Fraud.” For the terrible crime of counterfeiting cheese, “the International Cheese Syndicate,” or “InChSyn,” want to lock up Bruno. In a cocaine thrall, Egon riffs a bit at the sinister implications behind the scenes: “Cheese Fraud being a metaphor of course, a screen, a front for something more geopolitical, some grand face-off between the cheese-based or colonialist powers, basically northwest Europe, and the vast teeming cheeselessness of Asia.” Egon’s ranting here echoes the academic discussions of cheese back at the Airmont compound in Ch. 13, when discussion turns to breaking into the Asian markets: “How the heck do we create a market for dairy products in Japan short of invading and occupying the country outright? Taking away their tea or sake or whatever it is they drink and forcing them to drink milk like normal human beings?”

(Going back to Ch. 13 to find these lines, I realized that I’d neglected to include a Gothic reference in my riff on that chapter, where cheese is described as “a strange new form of life that was deliberately invented, like Doctor Frankenstein”).

Egon’s coked-up rant culminates in another of Shadow Ticket’s prophetic warnings of the Next Big War to Come. A glistening, entranced Egon declares:

“This is the ball bearing on which everything since 1919 has gone pivoting, this year is when it all begins to come apart. Europe trembles, not only with fear but with desire. Desire for what has almost arrived, deepening over us, a long erotic buildup before the shuddering instant of clarity, a violent collapse of civil order which will spread from a radiant point in or near Vienna, rapidly and without limit in every direction, and so across the continents, trackless forests and unvisited lakes, plaintext suburbs and cryptic native quarters, battlefields historic and potential, prairie drifted over the horizon with enough edible prey to solve the Meat Question forever…”

To repeat a claim I made in my last riff: Shadow Ticket is a bridge novel between two of Pynchon’s masterpieces, Against the Day and Gravity’s Rainbow.

And, to repeat another claim I’ve been making throughout these notes, as Hicks moves eastward, Shadow Ticket’s supernatural elements come closer to the foreground. He’s en route to Budapest, where, according to Egon, there “carouses a psychical Mardi Gras in every shade of the supernatural no matter how lurid.” We learn that “Budapest just at the moment is the metropolis and beating heart of asport/apport activities, where objects precious and ordinary, exquisite and kitsch, big and small, have been mysteriously vanishing on the order of dozens per day.” The “asport/apport” motif was first announced back in Ch. 4, via ex-vaudeville psychic Thessalie Wayward. Whereas folks back in Wisconsin were far more skeptical about — or at least reticent to openly speak about — the spooky stuff, Central Europe doesn’t try to deny it.

The chapter ends with Egon giving Hicks a present: a brand new type of pistol called the “Walther PPK.”

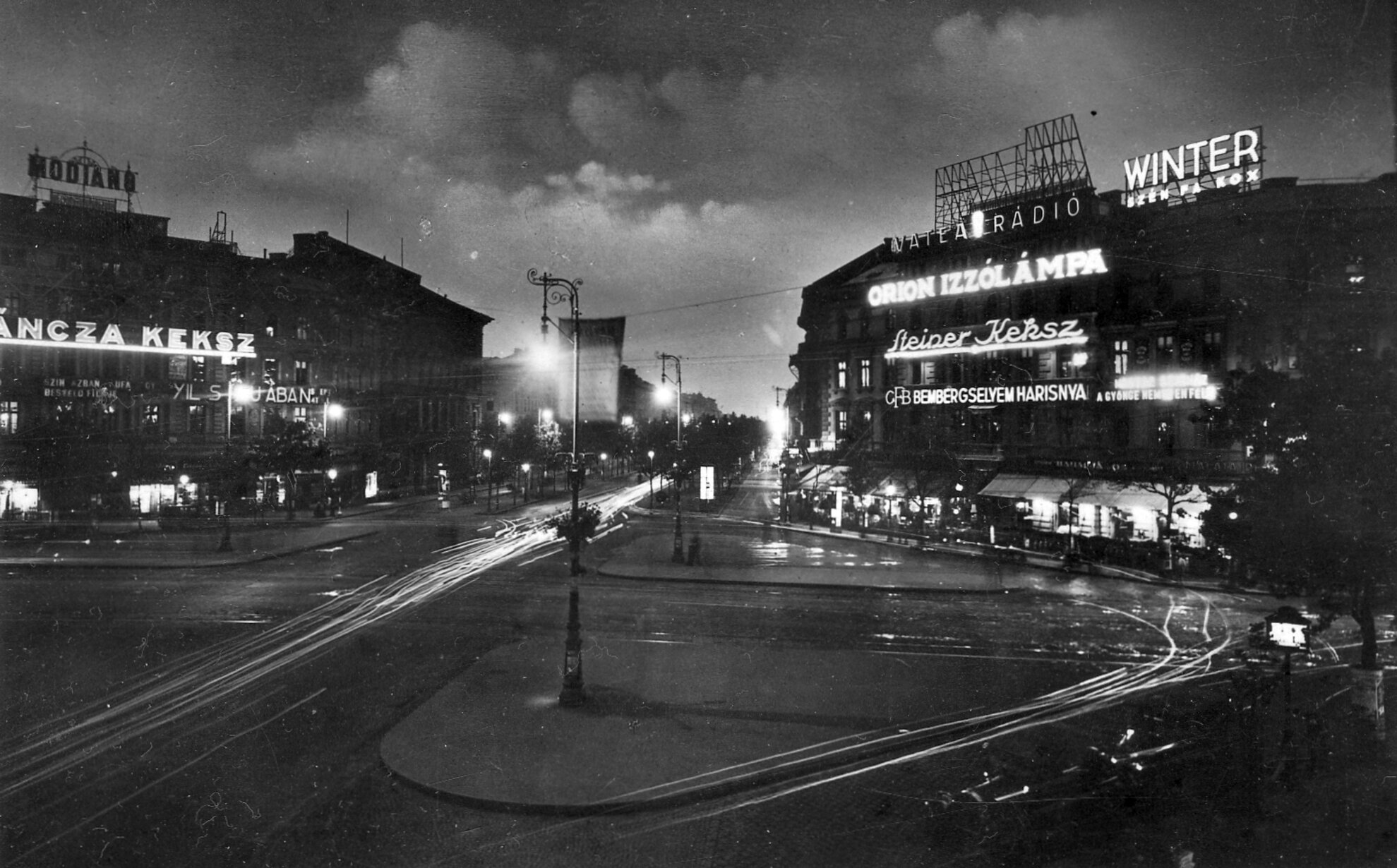

Chapter 22 begins in the Oktogon, a major intersection in Pest. Here, Hicks (and the readers) meet two new characters: Zoltán von Kiss, “once an echt working apportist, lately more of a psychic celebrity detective,” and motorcycle courier Terike who downplays her role as Zoltán’s “Glamorous Assistant.” Hicks is intrigued by Terike, and when she departs with “Szia!” — Hungarian for hello/goodbye, he responds with a “Hope so.” The pun is low hanging fruit but our boy Pynchon loves to eat from that tree.

Zoltán, or “Zoli,” as he prefers to be called has a mission for Hicks. But before getting into that (and a demonstration of his psychic and telekinetic powers), he distinguishes metaphysical Central Europe from concrete America:

“You are a practical people, Americans, everyone is either some kind of inventor or at least a gifted repairman. I myself have grown to rely too much on the passionate mindlessness which creeps over me just as an apport is about to arrive or depart. I am painfully aware of how much more exposure I need to the secular, material world.”

The phrase “passionate mindlessness” recalls Mindless Pleasures — a working title Pynchon used for what would become Gravity’s Rainbow.

But onto that mission: Hicks will assist in the recovery and return of “the crown jewel of tasteless lamps… known in underworld Esperanto as La Lampo Plej Malbongusto.” (Zoli’s ever-inflating description of the lamp’s tastelessness is pure Pynchon.) Again, we get an echo of the Airmont compound back in Ch. 13, where Hicks stumbled into “an excessive number of electric lamps… Some are unusual-looking, to say the least, and few if any in what you’d consider good taste.”

While the tasteless-lamp bit is, on the surface very goofy, it nevertheless highlights the novel’s concern with what can be seen and what remains unseen; with what casts a shadow, and with what is immaterial. Zolti posits the lamp’s recovery in language that approaches a holy restoration: “even the most hopelessly ill-imagined lamp deserves to belong somewhere, to have been awaited, to enact some return, to stand watch on some table, in some corner, as a place-keeper, a marker, a promise of redemption.” I think the notion here is beautiful answer to a rhetorical question posed in the opening nightmare of Gravity’s Rainbow: “Each has been hearing a voice, one he thought was talking only to him, say, ‘You didn’t really believe you’d be saved. Come, we all know who we are by now. No one was ever going to take the trouble to save you…‘ Pynchon is for the preterite; even the ugliest light-bearer is poised for redemption.

Hicks and Zoli eventually make their way to “a neighborhood of warehouses, corner taverns, cafés and hashish bars, metallic shadows, sounds of mostly invisible train traffic” and into speakeasyish spot “turbulent with kleptos conferring in Esperanto, featuring a lot of words ending in u (‘Volitive mood,’ comments Zoltán, ‘used for yearnings, regrets, if-onlys…’)” (When I was young my mother had a friend who was a member of an Esperanto society. The notion of an invented language fascinated me; I also recognized, even as a child, that it was a doomed project. I love that Pynchon includes a few nods to L. L. Zamenhof’s utopian linguistic project, and highlights the “yearning” behind the invented grammar.) After some funny business by a vaudevillian magic act trio called Drei Im Weggla (secret agents themselves, we’re assured parenthetically) and a nonviolent showdown with “Bruno Airmont’s deputy Ace Lomax,” Hicks fulfills his mission with Zoli.

Chapter 23 sees Hicks reunite with the Quarrenders. Pips has performed a quick change glamour, to Hicks’s admiration. She tells him it’s, All part of the craft, give whoever’s watching something blonde and shiny to fix their attention, then should one need to disappear, simply get rid of it and fade into the mobility.” Like Terike and the other sleight-of-hand artists of Shadow Ticket, Pips understands the value of posing as the “Glamorous Assistant.” Later in this chapter we’ll meet another spy, Vassily Midoff, of whom we’re told “Impressions of what he looks like also vary widely. Not that he’s invisible, exactly, people see him all the time, but they don’t remember that they saw him.”

Alf soon (literally) materializes and complains of an exhausting morning at the “Crossword Suicide Café.” Alf then goes on to detail how “an unemployed waiter named Antal Gyula steps in to what was then known as the Emke Café,” committed suicide, and left a “farewell note in the form of a crossword puzzle he designed himself, whose solution will reveal the reasons he did the deed, along with the names of other people involved.” The puzzle remained unsolved, a “crypto bonanza potentially and yet just as easily somebody’s idea of a practical joke.” The note is zany and sinister, silly and sad, utterly Pynchonian but also, like, totally real.

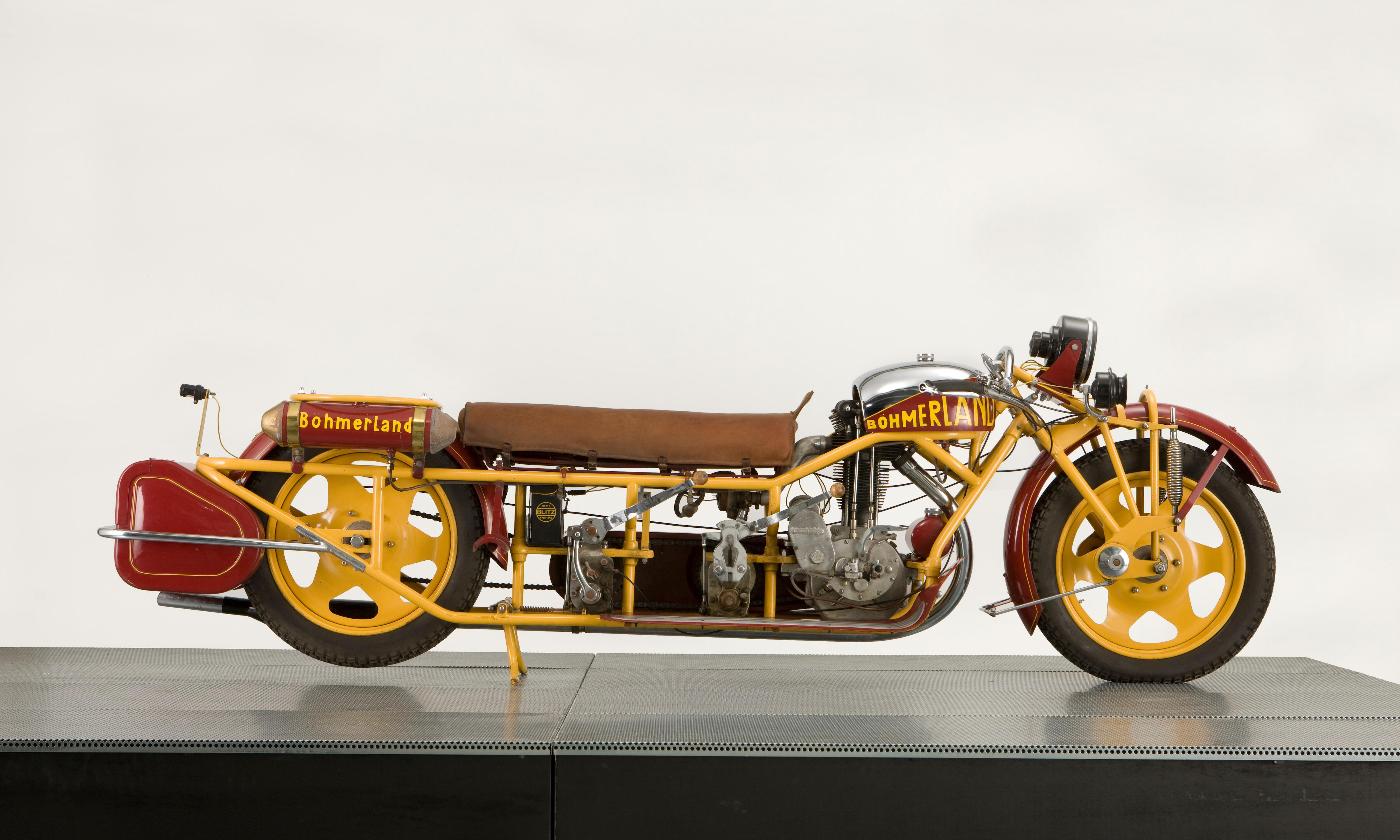

The chapter ends with the “nightclub apport trio Schnucki, Dieter, and Heinz, seated one behind another on a Böhmerland Long Touring motorcycle, ten and a half foot wheelbase, red and yellow paint job, riding patrol…” The spectacle upsets Vassily Midoff, who senses a fourth “invisible rider” at the motorcycle’s stern. He hits the high road, “spooked…back into invisibility,” the narrator noting that “for a trinity to be effective, and not just a set which happens to contain three members, there must be a fourth element, silent, withheld. A fourth rider, say, working a phantom gearbox…”

Perhaps the invisible fourth rider alludes to Carl Jung’s Answer to Job, which argues for a unified, reconciled quaternity, and not a trinity; a symbolic totality that acknowledges the shadow (ticket?) suppressed by the idealized triad. In Jung’s schema, the fourth element completes the cycle by restoring what has been excluded, granting wholeness rather than perfection. The phantom rider becomes an embodiment of that hidden completion, an invisible force that trails behind the spectacle of the three visible figures, suggesting that beneath their exuberant surface rides the unacknowledged presence that makes the whole thing work. (Or perhaps threatens to undo it.)