Right after WWII, the German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously declared that to write poetry after Auschwitz was barbaric. Adorno later recanted on his knee-jerk reaction, stating that “‘Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured have to scream… hence it may have been wrong to say that no poem could be written after Auschwitz.” Still, his initial proscription is often invoked as something of an imperative, or at least guiding principle, in 20th and 21st century art. Often stated boldly as “no poetry after Auschwitz,” it’s usually taken to mean that, after the horrors of the Holocaust, art has no valid aesthetic response to history, or perhaps even humanity, at least not in any of its traditional forms. Even more tricky, of course, is just how to represent the Holocaust itself. The severity of the event seems to call for a witnessing limited to facts alone, one devoid of any artifice or metaphor.

Over half a century later authors still wrestle with this issue. I just finished reading Yann Martel’s forthcoming novel Beatrice and Virgil, his follow-up to 2001’s Booker Prize-winning book club favorite, Life of Pi, a novel I’ve never read. (Beatrice and Virgil comes out mid-April and I’ll run a full review then). Very early in the book the protagonist Henry, a successful author, describes the book he is writing, a follow-up to his bestseller. It’s about:

the ways in which that event was represented in stories. Henry had noticed over years of reading books and watching movies how little actual fiction there was about the Holocaust. The usual take on the event was nearly always historical, factual, documentary, anecdotal, testimonial, literal. The archetypal document on the event was the survivor’s memoir, Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, for instance. Whereas war–to take another cataclysmic human event–was constantly being turned into something else. War was forever being trivialized, that is, made less than it truly is.

After waxing a bit more on artistic representations of war — romantic, epical, comedic, etc. — Henry seems to come about to Adorno’s point (never named in Martel’s text, for what it’s worth):

No such poetic licence was taken with–or given to–the Holocaust. That terrifying event was overwhelmingly represented by a single school: historical realism. The story, always the same story, was always framed by the same dates, set in the same places, featuring the same cast of characters.

Henry concedes a few exceptions to this rule, like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, before wondering:

why this suspicion of imagination, why this resistance to artful metaphor? A work of art works because it is true, not because it is real. Was there not a danger in representing the Holocaust in a way always beholden to factuality? Surely, amidst the texts that related what happened, those vital and necessary diaries, memoirs, and histories, there was a spot for the imagination’s commentary. Other events in history, including horrifying ones, had been treated by artists, and for the greater good.

Henry’s desire to write an artistic account of the Holocaust, or to write about how one writes about the Holocaust–to write a poetry (of sorts) after Auschwitz–does not, significantly, derive from any personal, historical, or cultural impetus. His concern seems, in many ways, an academic’s regard for aesthetic theory, leading him to envision his book as a split between fiction and essay, with the pieces being published in one book at “opposite” ends (i.e., one would have to flip the book upside down and over to access the text on the other side). What Henry fails to see–Henry, not Martel, let’s be clear–is that he has no legitimate response to the Holocaust. When pressed by a gang of editors, along with a bookseller and a critic, to answer the simple question “What is your book about?”, Henry retreats into a series of wonderfully vague literary generalities:

My book is about representations of the Holocaust. The event is gone; we are left with stories about it. My book is about a new choice of stories. With a historical event, we not only have to bear witness, that is, tell what happened and address the needs of ghosts. We also have to interpret and conclude, so that the needs of people today, the children of ghosts, can be addressed. In addition to the knowledge of history, we need the understanding of art.

But just what “the understanding of art” might mean here, Henry is unable to say. His book is shot down, and, thankfully, Martel’s book Beatrice and Virgil manages to be a novel-about-not-being-about-the-Holocaust-but-being-about-the-Holocaust-but-not-really-being-about-the-Holocaust, which is all for the better, really. (Did that sentence make any sense? No? Sorry. I promise to (attempt to) clarify in my full review of Beatrice and Virgil). Otherwise, Henry might have fallen into the sweet lull of what critic Lee Siegel has described as Nice Writing. Here’s an excerpt from Siegel’s 1999 essay “Sweet and Low”:

For at least the past decade, American writers have been pouring forth a cascade of horror stories about their condition or the condition of their characters. The Holocaust, ethnic genocide, murder, rape, incest, child abuse, cancer, paralysis, AIDS, fatal car accidents, Alzheimer’s, chronic anorexia: calamities drop from the printer like pearls. These are elemental events of radically different proportions, and the urge to make imaginative sense of them is also elemental. Some contemporary writers treat these subjects strongly and humbly and insightfully, but too many writers engaged in this line of production turn out shallow and distorted work. They seem merely to be responding to a set of opportunities created by a set of social circumstances. In their hands, human suffering goes unimagined, and the imagination goes hungry and deprived.

To return to Adorno’s dictum–no poetry after Auschwitz–the grim spectacle of history should not be fodder for “a set of opportunities created by a set of social circumstances.” Henry, a young French Canadian with no Jewish roots is utterly divorced from any authentic response to the Holocaust. He could write an academic essay on the subject, or a navel-gazing bit of metafiction that dithered over storytelling itself, but he essentially already has an answer to his own question of why there are so few artistic responses to the Holocaust–that to re-imagine or re-interpret or otherwise re-frame the real events of the Holocaust in art is to, at once, open oneself to dramatic possibilities of failure. Failure would derive from the radical inauthenticity of having merely used, rather than illuminated, one of history’s worst horrors (my verb “illuminate” here stands inauthentic, I admit). Henry–and perhaps, implicitly, Martel–eventually manages to respond to the Holocaust in his art, but I’ll save a discussion of that for a full review of Beatrice and Virgil.

In her debut novel, All the Living, C.E. Morgan tells the story of Aloma, a would-be pianist who forgoes her dreams of artistic freedom to play wifey to her young lover Orren who must take sole responsibility of running the family tobacco farm after his family dies in a car accident. Aloma knows nothing about farming and even less about the grief Orren suffers. She’s an orphan herself, but with no memory of her own parents, she finds it hard to connect to overworked Orren as he slowly slips away. A nearby minister who hires her to play church services paradoxically relieves and exacerbates Almoa’s despair when he enters her life. Morgan’s novel is a slow-burn, often painful, sometimes slow, but also guided by a poetic spirituality that resists easy interpretations. (Oh, and she’ll also make you run for a thesaurus every few pages). All the Living is new in trade paperback from Picador, available now.

In her debut novel, All the Living, C.E. Morgan tells the story of Aloma, a would-be pianist who forgoes her dreams of artistic freedom to play wifey to her young lover Orren who must take sole responsibility of running the family tobacco farm after his family dies in a car accident. Aloma knows nothing about farming and even less about the grief Orren suffers. She’s an orphan herself, but with no memory of her own parents, she finds it hard to connect to overworked Orren as he slowly slips away. A nearby minister who hires her to play church services paradoxically relieves and exacerbates Almoa’s despair when he enters her life. Morgan’s novel is a slow-burn, often painful, sometimes slow, but also guided by a poetic spirituality that resists easy interpretations. (Oh, and she’ll also make you run for a thesaurus every few pages). All the Living is new in trade paperback from Picador, available now. Anne Michaels’s The Winter Vault begins in Egypt, in 1964, where Canadian engineer Avery Escher is part of a team trying to help the Nubians who will be displaced by the Aswan High Dam. He and his wife Jean share a houseboat on the Nile, but what might have been a year of romantic adventure devolves into the tragedy of a culture displaced and a family eroded. The pair separate and return to Canada, where Jean takes up with Lucjan whose stories of Nazi-occupied Warsaw inform the novel’s second half. The Winter Vault is poetically dense and often overly-lyrical, sometimes offering self-important and ponderous dialogues in place of concise plotting. And while Michaels treats the tragedies of the occupied Poles and Nubians with a certain sensitivity, her engagement veers awfully close to what Lee Siegel has termed “Nice Writing.” The Winter Vault is new in trade paperback from Vintage on April 6, 2010.

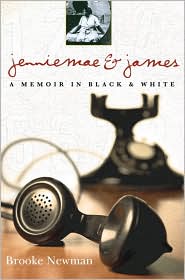

Anne Michaels’s The Winter Vault begins in Egypt, in 1964, where Canadian engineer Avery Escher is part of a team trying to help the Nubians who will be displaced by the Aswan High Dam. He and his wife Jean share a houseboat on the Nile, but what might have been a year of romantic adventure devolves into the tragedy of a culture displaced and a family eroded. The pair separate and return to Canada, where Jean takes up with Lucjan whose stories of Nazi-occupied Warsaw inform the novel’s second half. The Winter Vault is poetically dense and often overly-lyrical, sometimes offering self-important and ponderous dialogues in place of concise plotting. And while Michaels treats the tragedies of the occupied Poles and Nubians with a certain sensitivity, her engagement veers awfully close to what Lee Siegel has termed “Nice Writing.” The Winter Vault is new in trade paperback from Vintage on April 6, 2010. Jenniemae & James is Brooke Newman‘s new memoir about her father’s unlikely relationship with the family maid. James Newman was a brilliant mathematician (he coined the term “googol”); Jenniemae Harrington “was an underestimated, underappreciated, extremely overweight woman who was very religious, dirt poor, and illiterate.” Newman wants us to see a unique–and deep–friendship between the pair that defies 1940s/50s norms in Washington D.C., but it’s hard not to think that there’s at least some whitewashing going on here. Undoubtedly the two shared an affinity and connected through a love of numbers, but it’s hard to see more in this than an employer-employee relationship–and one still colored by the politics of the pre-Civil Rights era. Jenniemae, black mammy, sassy, Southern, larger-than-life, quick with folk wisdom and colorful quips–it all seems like a one-sided vision, a take on the Magical Negro trope that resists human complexity. Still, Newman’s tone is sincere, her pacing is swift, and the book reads with the pathos that memoir lovers demand. Jenniemae & James is new in hardback from Harmony/Random House March 30, 2010

Jenniemae & James is Brooke Newman‘s new memoir about her father’s unlikely relationship with the family maid. James Newman was a brilliant mathematician (he coined the term “googol”); Jenniemae Harrington “was an underestimated, underappreciated, extremely overweight woman who was very religious, dirt poor, and illiterate.” Newman wants us to see a unique–and deep–friendship between the pair that defies 1940s/50s norms in Washington D.C., but it’s hard not to think that there’s at least some whitewashing going on here. Undoubtedly the two shared an affinity and connected through a love of numbers, but it’s hard to see more in this than an employer-employee relationship–and one still colored by the politics of the pre-Civil Rights era. Jenniemae, black mammy, sassy, Southern, larger-than-life, quick with folk wisdom and colorful quips–it all seems like a one-sided vision, a take on the Magical Negro trope that resists human complexity. Still, Newman’s tone is sincere, her pacing is swift, and the book reads with the pathos that memoir lovers demand. Jenniemae & James is new in hardback from Harmony/Random House March 30, 2010