Does [the novel’s] ironic tone (which often feels like a reflex, a tic) preclude sincerity? Is all this talk of community no more than an artful confection, the purest kind of cynicism? The question is impossible to resolve, so each of these episodes — and indeed the book as a whole — takes on a sort of hermetic undecidability.

Ryan Chang: Hey man, I just skimmed the NYT review—per the excerpt you provided—because I don’t want Kunzru clouding any of my response. It’s certainly a question I too grapple with, and I think Kunzru is right insofar that the question is “undecidable” but not for the reason(s) he suggests. I agree with you that he dodges the question, whether or not from editorial pressure or a reticence to actually address “hermetic undecidability.”

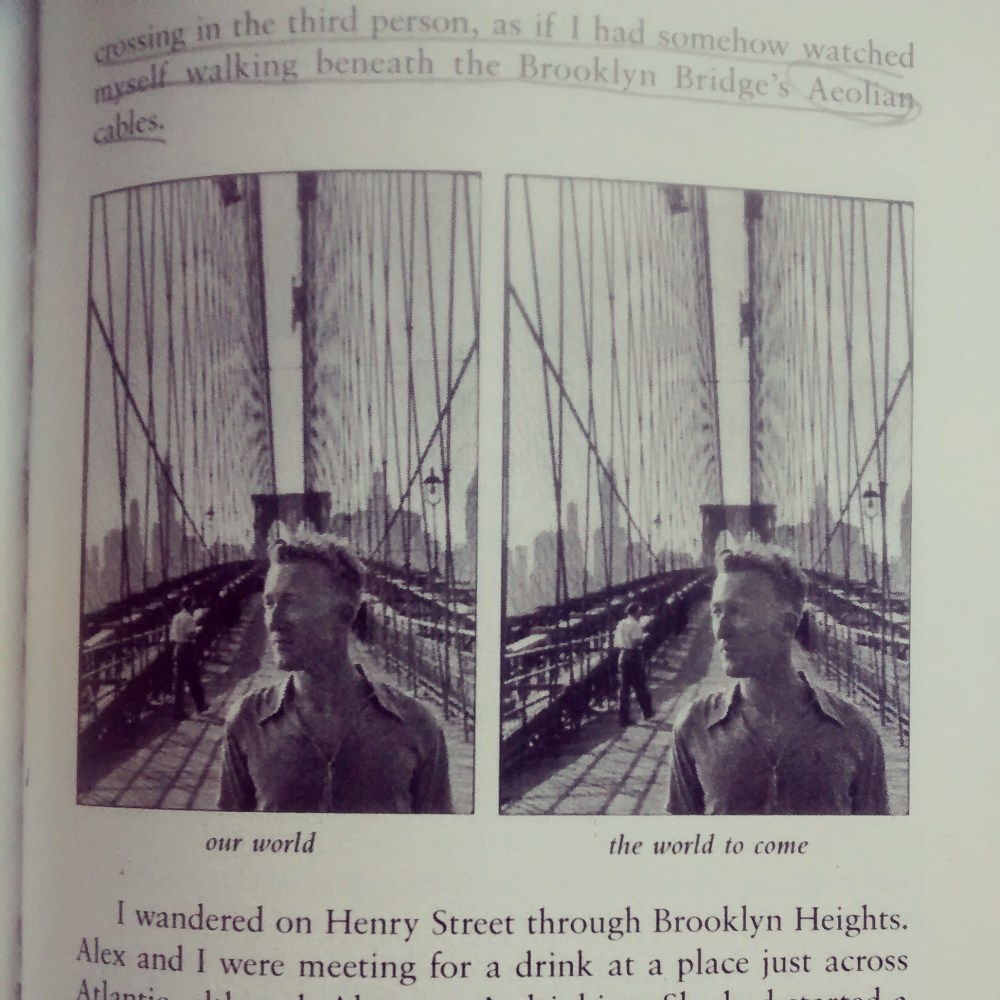

For one, I’m not sure myself if The Author ever arrives at the Whitmanic model of democracy he posits. I’m also not sure if he is supposed to “arrive” in the sense that a finality is set. I guess I also want to riff a bit on how finality might be described. Is finality then something static; as in, somehow 10:04 transmits–electrocutes, reverberates–through its readership, now coeval (the when negligent, the position of the reader enmeshed in the text is the same at 10 PM here as it is at 5 AM there), the novel’s theses and everything is suddenly Whitmanic? Community successfully reimagined and cemented? That sounds too easy, too convenient, too short-sighted. Or is it a kind of arrival into an embodiment of time that exists outside of conventional literary clocks, which is also a Market-based clock — it’s my sense that the kind of democracy Whitman envisions in his work is one constantly in flux, a “reality in process” and thus in opposition to the capitalist clock? That is, we know we are supposed to “stop” working at 5, the embodiment of the currency-based clock disappears after 5, but it’s a contrasting relationship. Our time outside of the currency then absorbs a negative value (I think The Author only mentions once or twice how we are all connected by our debt, a negativity projected into the future), though the illusion of the clock is that we are “free” in our time. OK: in a literary sense, wouldn’t this be a sense of a text’s world stopping, a suspension that retroactively pauses the whole book? That 10:04 ends not only with a dissolution of prose into poetry, but also The Author into Whitman and thus recasting the first-/third-person narrator into a lyric-poet mode suggests the book’s integration into our, the reader’s, time (and also, retroactively, the entirety of the text). In that sense, for me, the issue whether or not The Author of 10:04 integrates the book fully into a Whitmanic model is not necessarily the point — it is that he, and also we hopefully through him — actively participate in remaking a “bad form of collectivity” less so. Continue reading “A Conversation about Ben Lerner’s Novel 10:04 (Part 2)”