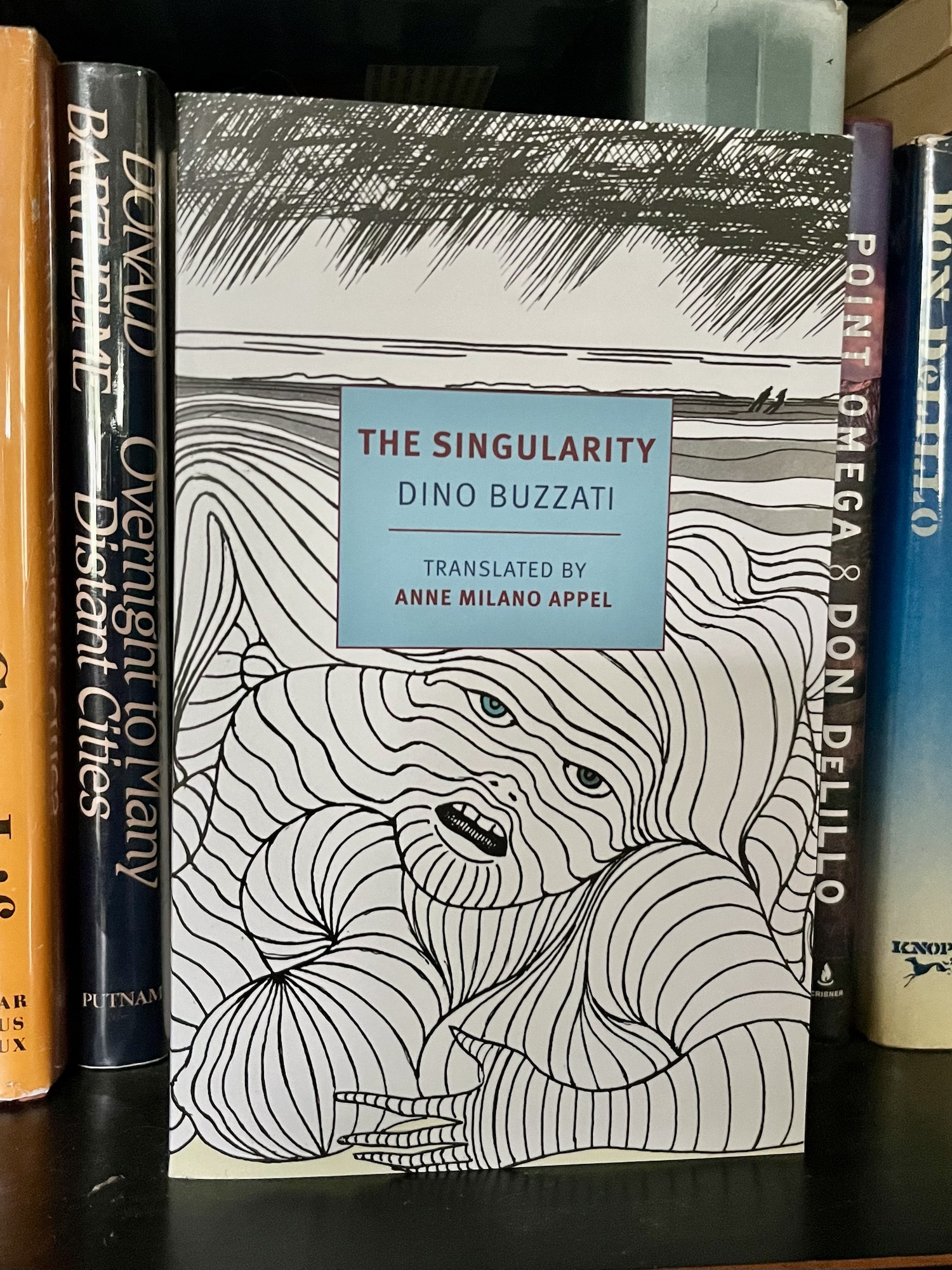

Got a review copy of Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste, a slim lil fellow from NYRB in translation by Charlotte Mandell. The back cover includes a blurb from William H. Gass—

Monsieur Teste is a monster, and is meant to be—an awesome, wholly individualized machine—yet in a sense he is also the sort of inhuman being Valéry aimed to become himself: a Narcissus of the best kind, a scientific observer of consciousness, a man untroubled by inroads of worldly trivia, who vacations in his head the way a Platonist finds his Florida in the realm of Forms.

What the fuck does Gass mean by “Florida” here? I really want to know.

This style of post, the book acquired post, is an established, which is to say tired, blog post format on this blog, Biblioklept, probably going back a decade now, born from a glut of review copies piling up, mostly unasked for but many asked for, books that stack up their own measures of guilt, unread, or then maybe read, months, years later—but the post style is ephemeral, yes, fluffy, sure, embarrassing even maybe. The form is stale; I apologize. I do think the Valéry book seems pretty cool.

I have a not-insubstantial stack of newly acquired new (and used books) stacked on the cherry side table by the black leather couch that I should have made book acquired posts about. These have piled up over the last few weeks. These are not interesting sentences (several of the books seem very interesting).

I am not going to find the new form I want here, am I?

When I was a freshman in high school, my then-girlfriend’s older brother gave me a mixtape that a girl had given him. He didn’t like anything on the mixtape; he liked Buddy Holly. I can’t remember why he gave me the tape—I think I saw it in his car and asked about it. But it ended up changing my life in some ways, as small giant things like songs or books or films can do when they come over you at the right time and place.

There were a few bands on the tape that I knew or had heard of, and even some I owned albums by, like the Cure and the Smiths. But for the most part, the tape opened a new aural world to me. I heard My Bloody Valentine, Big Star, Ride, the Cocteau Twins, and This Mortal Coil, among others, for the first time. There were also two songs by one band: Slowdive’s “When the Sun Hits” and “Dagger.”

(This particular blog post is no longer about acquiring a Valéry translation; it is about something else.)

Those songs are from Slowdive’s 1993 classic Souvlaki. I owned it on cassette. That cassette melted, just slightly, on the top of my 1985 Camry’s dashboard in like August of 1995. The tape was just warped enough not to fit into a cassette deck. I liked to imagine how it would sound. The next year, my lucky privileged ass found a used CD of Slowdive’s follow-up, Pygmallion on a school trip to London. Slowdive kinda sorta broke up after that.

I have always been a proponent of bands breaking up. I think a decade is long enough; get what you need done in five or six albums and move on. There are many many exceptions to this rule. But generally, I don’t think beloved bands—by which I means bands beloved by me—should keep going on too long. And if they break up, they should stay broken.

But I bought Slowdive’s 2017 reunion album Slowdive used at a St. Petersburg record store and listened to it again and again, amazed at how strong it was, how true to form. My kids liked it a lot. And then they put out a record last year, Everything Is Alive—I like that one too (not as good as the self titled one).

(There’s no point to any of this; I might’ve had some wine; I might just feel like writing.)

I guess if you’d told me back in ’95 or ’05 or even ’15 that I’d see a reunited Slowdive twice in one year I’d say that that sounded silly. (The ’15 version of me that had seen Dinosaur Jr.’s dinosaur act wouldn’t have been interested.) But we went out into the woods to see Slowdive this Sunday. They played the St. Augustine Amphitheatre to a large, strange, diverse crowd, out there in the Florida air. A band named Wisp, TikTok famous I’m told, opened, and they were pretty good. But Slowdive was perfect—better than back in May in Atlanta—echo and reverb ringing out into Anastasia State Park.

We stayed in a cheap motel off of AIA that night—another sign of my age. When I was younger, I could drive six hours, watch a band, and drive the six hours back without blinking. We are about 45 minutes from St. Augustine. It was a nice night out.

A younger version of me could’ve read the 80 pages of Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste in the time it took to twiddle my thumbs in this post and write a real (and likely bad) review to boot. Again, apologies. I’m getting old, a dinosaur act. But I can’t break up, not now.

Slowdive, St. Augustine Amphitheatre, 10 Nov. 2024

Slowdive, St. Augustine Amphitheatre, 10 Nov. 2024