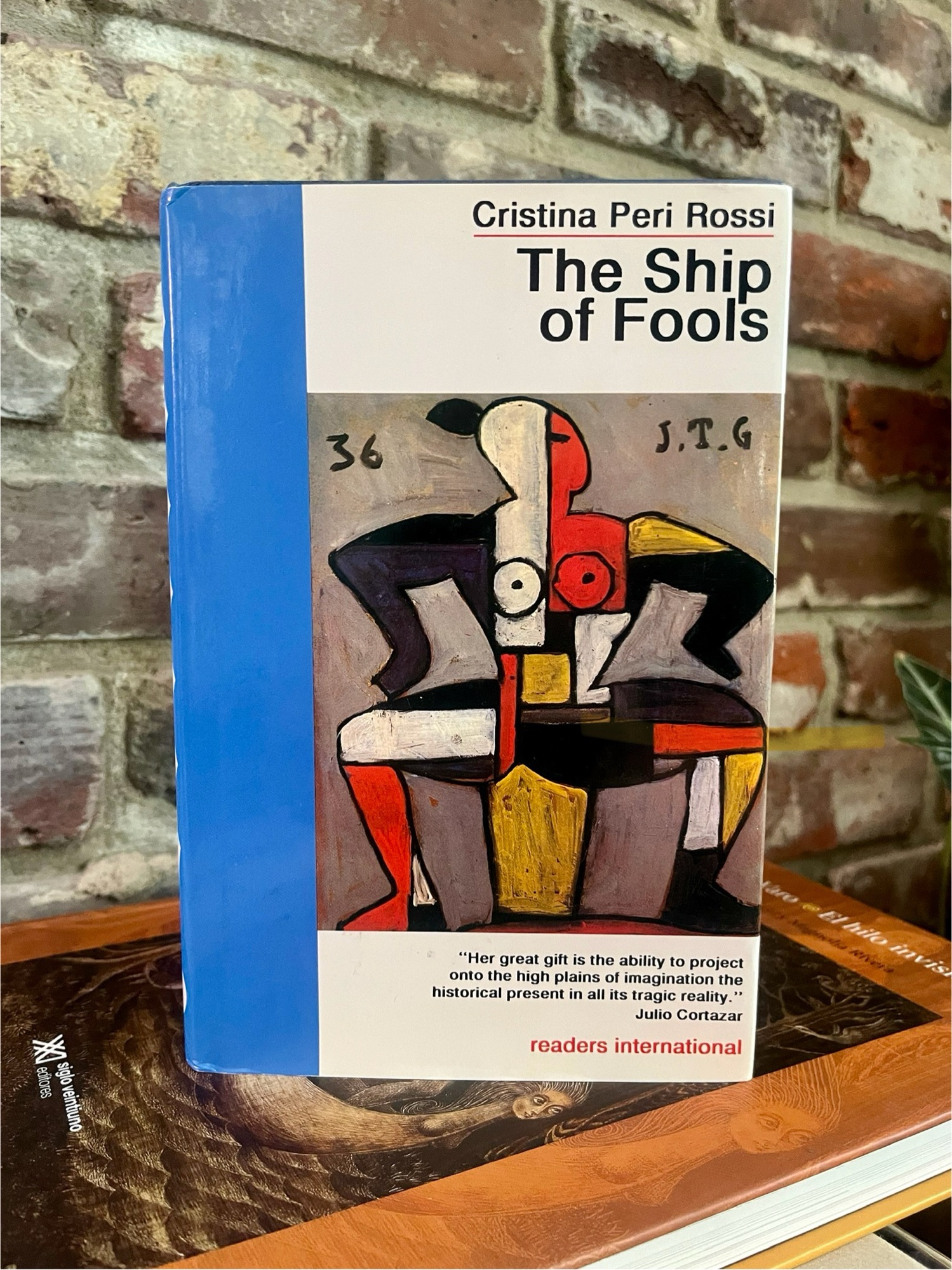

The Ship of Fools by Cristina Peri Rossi, first published in 1984 and released in English translation by Psiche Hughes in 1989, is a novel of dislocation—political, psychological, and existential. Its protagonist, Ecks, drifts from place to place in a world that feels suspended between dream and memory, never quite solid: “He felt he was travelling not in space but backwards in time.” That sense of slippage—temporal, emotional, narrative—is central to the book’s effect.

Plot is secondary, if it exists at all. The novel drifts like a bottle at sea: beautiful, opaque, marked by the presence of something urgent inside—but sealed, floating, unmoored. Like Renata Adler’s Speedboat or Ann Quin’s Passsages, this is a novel that prefers jump cuts to journeys, broken signals to neat resolutions. It unfolds in fragments, circular musings, moments of stasis that shimmer with strange possibility. At one point, a character suggests that “conversation is more a question of style than ideas,” a description of the novel itself. Style is idea in The Ship of Fools. The syntax itself seems to think.

There are recurring characters, loose thematic arcs, and strange moments of connection, but the novel often seems to turn away from linearity. It’s what the book itself calls “a story without progress,” or perhaps a tapestry of passing encounters and unresolved longings. There’s a Bolañoesque sense of drift to it, too—a wandering narrator collecting impressions like scars, haunted by disappearances that resist explanation. At the same time, there’s something in the intensity of The Ship of Fools—its visceral depictions of trauma and social rupture—that evokes the furious lyricism of Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season. Both authors understand that political horror isn’t always best addressed by realism—it seeps in more disturbingly through atmosphere, voice, and repetition.

Peri Rossi was herself an exile, having fled the civic-military dictatorship of Uruguay in 1972. She fled the regime, first to Barcelona and later Paris, and this personal history pulses quietly through every page. The Ship of Fools isn’t autobiographical in the conventional sense, but its texture is soaked with the disorienting logic of exile: the sense of being always elsewhere, never quite present, both seen and unseen.

One of the pleasures of The Ship of Fools is the way it captures fleeting impressions in striking, lyrical language. Descriptions of people and places often feel like fragments from a half-remembered dream. The narrator describes a girl “bursting with youth; with that radiant beauty which, more than a quality of feature or of line, is the result of organic perfection that only later would begin to fall apart, breaking its essential but precarious harmony.” Elsewhere, the sea is evoked with the precision of a surrealist painting: “Green eyes and wide sea, swinging hips and plunging necklines. The sea was rolling like the water in a glass. Or the ship was. The ship was a glass floating on the high tide.” It’s not hard to imagine Jodorowsky filming this image—bodies on a tilting horizon, symbolic without being decipherable.

Beneath the dreamlike surface runs a steady current of political urgency. Ecks is an exile, and many of the novel’s characters—some named, some merely sketched—are displaced or disappeared. “To disappear is no longer voluntary,” the narrator tells us, “but acquires passive form: ‘We are being disappeared.’” It’s a haunting line that collapses grammar and violence in a single breath. One character, laboring in a sinister “camp for the disappeared,” wonders “if there was still any point in measuring time by the clock, when it seemed like ten years to him and twenty to his friend suffering agonies about him.” These grim lines are delivered without sentimentality, but with unmistakable clarity. The book never lectures. It haunts instead.

The novel’s philosophical core is found in its reflections on art, memory, and identity. One of the longest and most striking passages describes the medieval Tapestry of Creation:

There the missing parts unfurl, fragments intimating the larger harmony of the universe. What we love in any structure is a vision of the world that gives order to chaos, an hypothesis which is comprehensible and restores our faith, atoning for our having fled and scattered before life’s brutal disorder. We value in art the exercise of mind and emotion that can make sense of the universe without reducing its complexity. Immersed in such art one could live one’s life, engaged in a perfectly rational discourse whose meaning cannot be questioned because it resides in an image containing the whole universe.

What surprises and will always surprise is the notion that a single mind could conceive of such a convincing and pleasing structure, moreover a happy one, a structure which as well as being a metaphor is also a reality.

This longing for order—however temporary or illusory—is deeply felt throughout the novel, even as its own structure resists resolution. The moment we seek meaning, it slips sideways. Identity, like narrative, fractures under pressure.

That same ambiguity runs through the book’s treatment of gender. Lucía, one of the more vivid figures in Ecks’s drifting life, is described as “dressed in men’s clothes,” her appearance perfectly androgynous. Ecks is both drawn to and overwhelmed by her. “He saw the unfolding of two parallel worlds… yet inseparably connected in such a way that the triumph of one would cause the death of both.” Later, another character remarks, “Don’t we all attribute ourselves a sex? And spend our lives proving it?” Gender is not a stable identity but a performative act—one repeated until it congeals into something that passes for truth.

Memory and history, too, are always in motion. “Ship captains and sailors of the past were those who best knew the universe,” the narrator reflects. Their journals once held the world’s accumulated knowledge: “One referred…to these journals” to understand distant plants, animals, and stars. But now, “they stopped writing and their main tasks became trade and war…Their journeys are now shorter and safer. But also less interesting.” It’s a quiet lament for a world that’s abandoned curiosity for control.

Ecks himself seems increasingly hollowed out by this world. “I stopped my work. Since then wheat and chaff have mixed. Under the grey sky the horizon is a smudge, and no voice answers.” His sense of loss—of self, of direction, of connection—is profound. “I shall lose,” he thought, and then: “I’ve already lost.” Like a Bolaño narrator spiraling through half-empty towns or an Ann Quin character trying to read meaning into chaos, he is less a man than a vessel for disappearance.

And yet, The Ship of Fools still finds a kind of poetry in this fragmentation:

Dreams have their own logic; only in the ambiguity of daylight do we need to reason and compare, to pin down the weft of things. Dreams are so persuasive, they need no argument.

Peri Rossi’s novel lives in that twilight logic, where estrangement becomes its own kind of truth. Exile, here, is not just a matter of borders—it is a way of seeing. “Those who live always in the same place… do not realize that to be a stranger is a temporary situation, one that can be altered; in fact they assume that some men are strangers and others not. They believe that one is born — and does not become — a stranger.” In The Ship of Fools, everyone becomes a stranger, even to themselves.

In the end, the novel is both deeply political and deeply personal. It captures what it feels like to live under systems that make life feel increasingly unreal, to grasp for meaning in a world of exiles and silence, to lose and keep losing—and yet keep imagining, keep remembering, keep writing. Our days, the novel suggests, “are no different from the past, except in the number of tyrants, their systematic methods and the cold logic with which they lead the world to madness.”

Although it is often bitterly funny, The Ship of Fools is not a cheerful book. But it lingers like a half-remembered dream, like the texture of a forgotten language, like a map you keep reading even after the landmarks have vanished. Very highly recommended.