Previously:

Not-really-the-rules recap:

I will focus primarily on novels here, or books of a novelistic/artistic scope.

I will include books published in English in 1975; I will not include books published in their original language in 1975 that did not appear in English translation until years later. So for example, Thomas Bernhard’s Korrektur will not appear on this list because although it was published in German in 1975, Sophie Wilkins’ English translation Correction didn’t come out until 1979.

I will not include English-language books published before 1975 that were published that year in the U.S.

I will fail to include titles that should be included, either through oversight or ignorance but never through malice. For example, I failed to include Dinah Brooke’s excellent 1973 novel Lord Jim at Home in my Best Books of 1973? post because I didn’t even know it existed until 2024. Please include titles that I missed in the comments.

So, what were some of the “Best Books of 1975?”

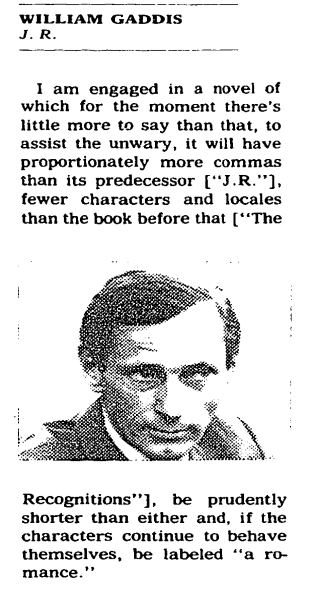

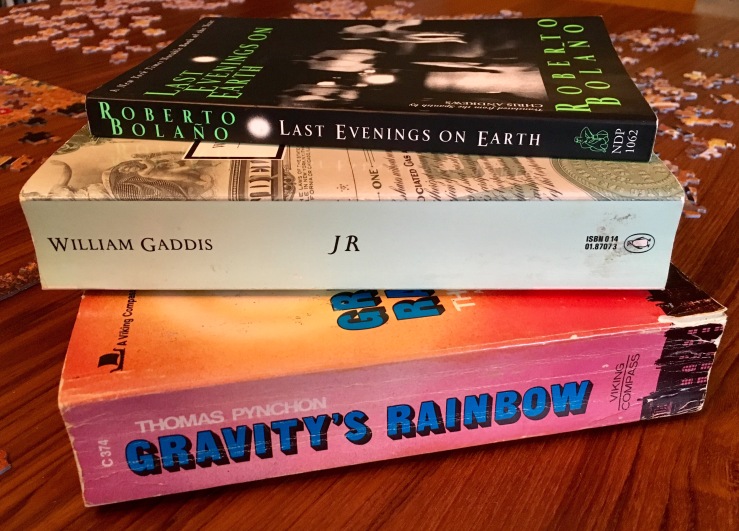

William Gaddis’s novel J R, one of the greatest 20th c. American novels, was published in 1975. I’ll make note of it first as an artistic ballast against the commercial list I’m about to offer up: The New York Times Best Seller list for 1975.

James Michener’s 1974 novel Centennial dominates the NYT list through winter and spring of 1975 (save for a brief one-week blip when Joseph Heller’s 1974 novel Something Happened published in paperback). By the summer, Arthur Hailey’s The Moneychangers rose to the top of the bestseller, the first novel of 1975 to do so. Judith Rossner’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar and E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime competed for the top slot throughout the fall of ’75, with Agatha Christie’s final Poirot novel Curtain taking over in the winter.

My sense is that of these bestsellers, Ragtime‘s critical reputation has probably endured the strongest. The editors of the NYT Book Review included Ragtime in their 28 Dec. 1975 year-end round-up, along with Donald Barthelme’s The Dead Father, Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, Peter Handke’s A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, Peter Matthiessen’s Far Tortuga and V. S. Naipaul’s Guerrillas.

William Gaddis’s J R won the 1976 National Book Award for fiction; Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory took the NBA for nonfiction; the NBA for poetry went to John Ashberry’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, and Walter D. Edmond’s Bert Breen’s Barn won the NBA for children’s literature. NBA finalists that year included Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, Vladimir Nabokov’s story collection Tyrants Destroyed, Johnanna Kaplan’s Other People’s Lives, Larry Woiwode’s Beyond the Bedroom Wall, and The Collected Stories of Hortense Calisher. (Robert Stone’s excellent 1974 novel Dog Soldiers won the 1975 NBA, if you’re keeping track).

If Bellow was sore about losing the NBA to Gaddis, he could console himself with the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for Literature (for Humboldt’s Gift). The 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature went to Eugenio Montale “for his distinctive poetry, which, with great artistic sensitivity, has interpreted human values under the sign of an outlook on life without illusions.” Montale did not publish a book in 1975.

The 1975 Booker Prize shortlisted only two of eighty-one novels (both published in 1975): Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Heat and Dust and Thomas Keneally’s Gossip From the Forest. Heat and Dust took the prize.

The American Library Association’s Notable Books of 1975 list echoes many of the titles we’ve already seen, as well as some interesting outliers: Andre Brink’s self-translation of Looking on Darkness (banned by South Africa’s apartheid government), Alan Brody’s Coming To, Ben Greer’s prison novel Slammer, Dagfinn Grønoset’s Anna (translated by Ingrid B. Josephson), Donald Harrington’s The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks, Anne Sexton’s The Awful Rowing toward God, and Mark Vonnegut’s memoir The Eden Express.

The National Book Critics Circle Awards for 1975 were Doctorow’s Ragtime, R.W.B. Lewis’s biography Edith Wharton, Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, and Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory.

The 1975 Nebula Awards long list is particularly interesting. Along with sci-fi stalwarts like Poul Anderson, Alfred Bester, and Roger Zelzany, the Nebulas expanded their reach to include Doctorow’s Ragtime and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. William Weaver’s translation of Invisible Cities was actually published in 1974 — as was the Nebula winner for 1975, Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. Significant Nebula Awards shortlist titles published in 1975 include Joanna Russ’s The Female Man, Robert Silverberg’s The Stochastic Man, and Tanith Lee’s The Birthgrave. Most notable though is the inclusion of Samuel R. Delaney’s cult classic Dhalgren.

The 1976 Newberry Award went to Susan Cooper’s 1975 novel The Grey King; the Newberry Honor Titles were Sharon Bell Mathis’s The Hundred Penny Box (illustrated by Diane and Leo Dillon) and Laurence Yep’s Dragonwings. Other notable books for children and adolescents published in 1975 include Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, Beverly Cleary’s Ramona the Brave, and Roald Dahl’s Danny, the Champion of the World.

Awards aside, commercial successes for 1975 included Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, Joseph Wambaugh’s The Choirboys, Jack Higgins’s The Eagle Has Landed, James Clavell’s Shōgun, Michael Crichton’s The Great Train Robbery, Lawrence Sanders’s Deadly Sins, and Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda.

Some critical/cult favorites (and genre exercises) from 1975 include: Martin Amis’s Dead Babies, J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man, Charles Bukowski’s Factotum, Rumer Godden’s The Peacock Spring, Xavier Herbert’s insanely-long epic Poor Fellow My Country, Gayl Jones’s Corregidora, David Lodge’s Changing Places, Bharati Mukherjee’s Wife, Gary Myers’s weirdo fiction collection The House of the Worm, Tim O’Brien’s debut Northern Lights, James Purdy’s In a Shallow Grave, James Salter’s Light Years, Anya Seton’s Smouldering Fires, Gerald Seymour’s Harry’s Game, Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy, Glendon Swarthout’s The Shootist, and Jack Vance’s Showboat World.

I’ve only read about fifteen books mentioned here (although I’ve abandoned several of them more than once (I’m looking at you Illuminatus! Trilogy and Dhalgren), so my own “best of 1975” list is uninformed and provisional, and frankly pretty obvious to anyone who checks in on this blog semi-regularly. My picks for ’75: J R, William Gaddis; The Dead Father, Donald Barthelme; High-Rise, J.G. Ballard.