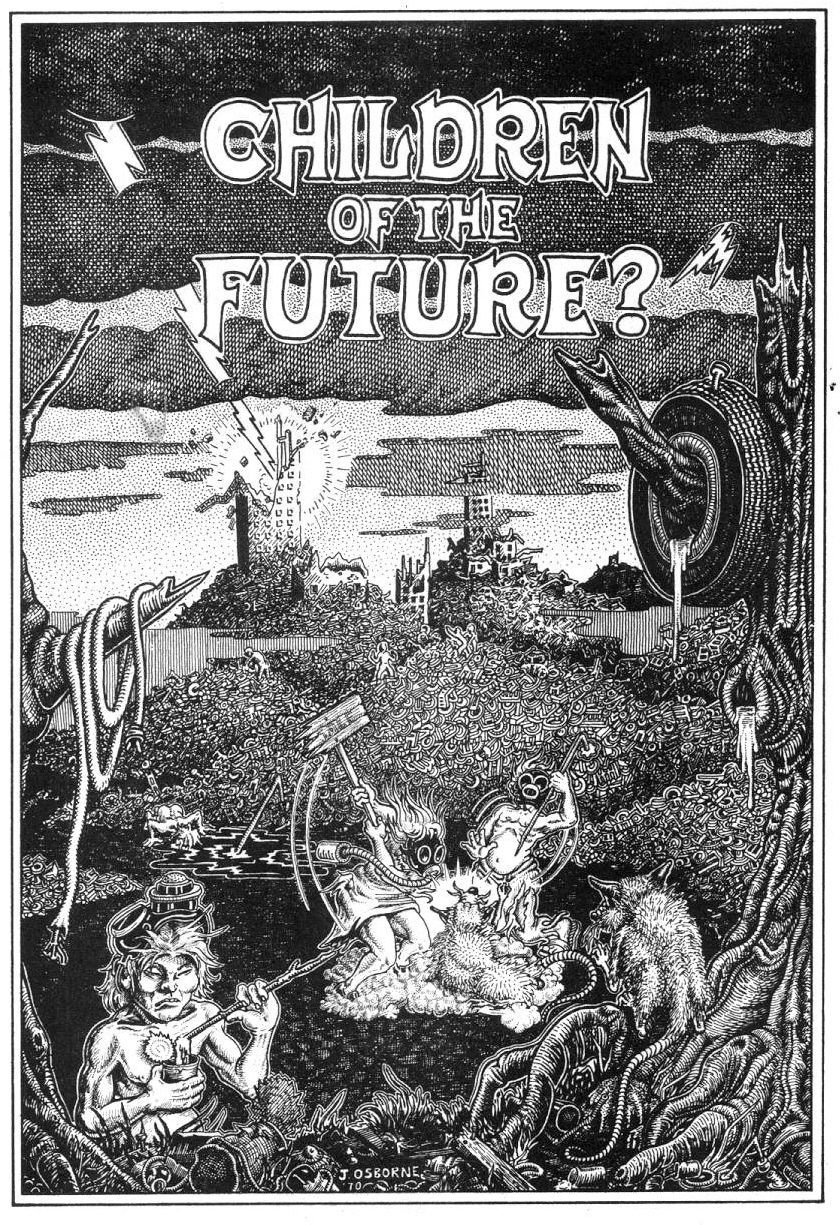

“Children of the Future?” a one-pager by Jim Osborne. From Slow Death Funnies #1, April, 1970, Last Gasp.

“Children of the Future?” a one-pager by Jim Osborne. From Slow Death Funnies #1, April, 1970, Last Gasp.

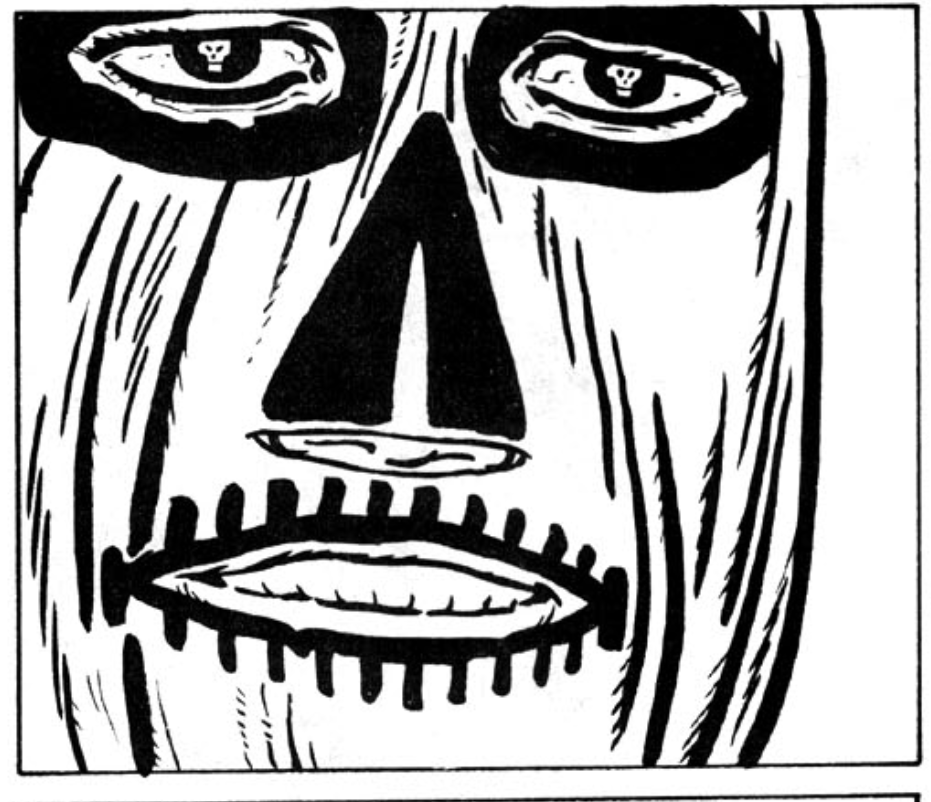

From “Nightmare World” by Basil Wolverton. Published in Weird Tales #3, Sept. 1952, Stanely Morse Publications.

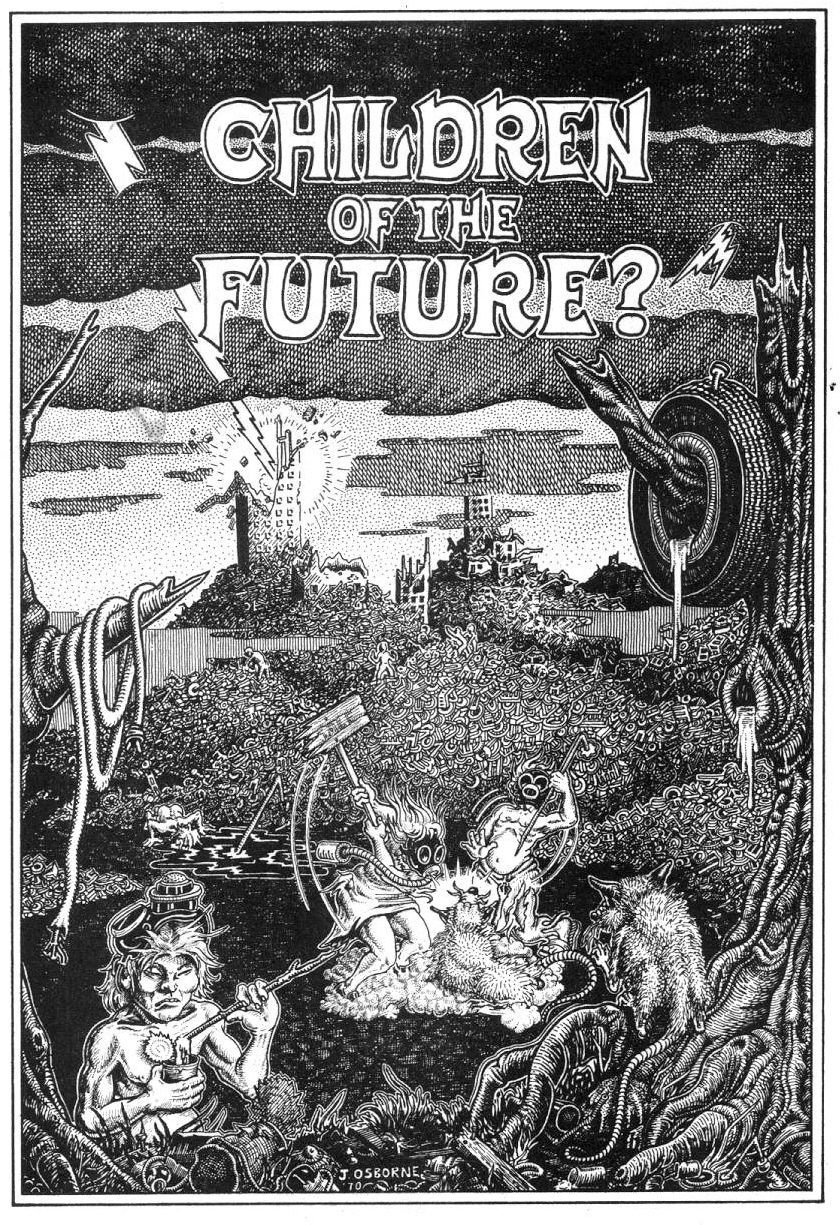

A page from Ben Passmore’s graphic novel Black Arms to Hold You Up, Pantheon, 2025. Assata Shakur passed away on 25 Sept. 2025. She was free.

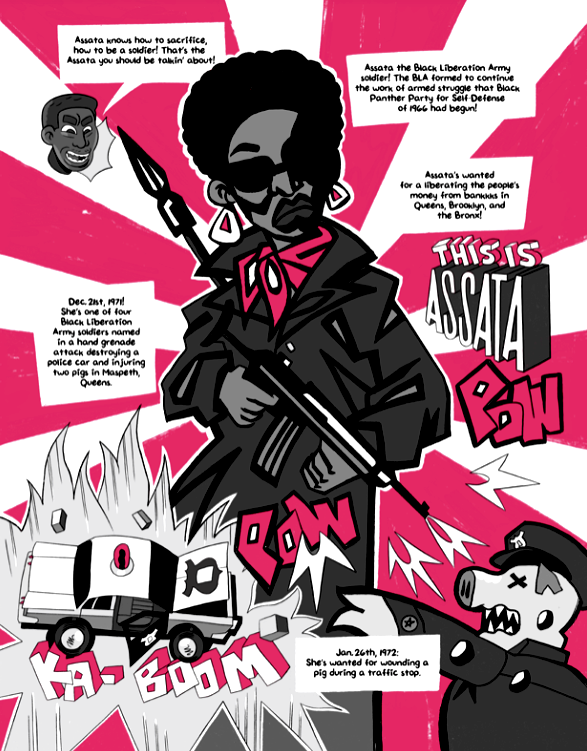

A one-pager by Robert Crumb from Weirdo #2, Summer 1981, Last Gasp.

A one-panel gag by Jay Lynch (as “Phil Space”) from Gothic Blimp Works #3, 1969, the East Village Other.

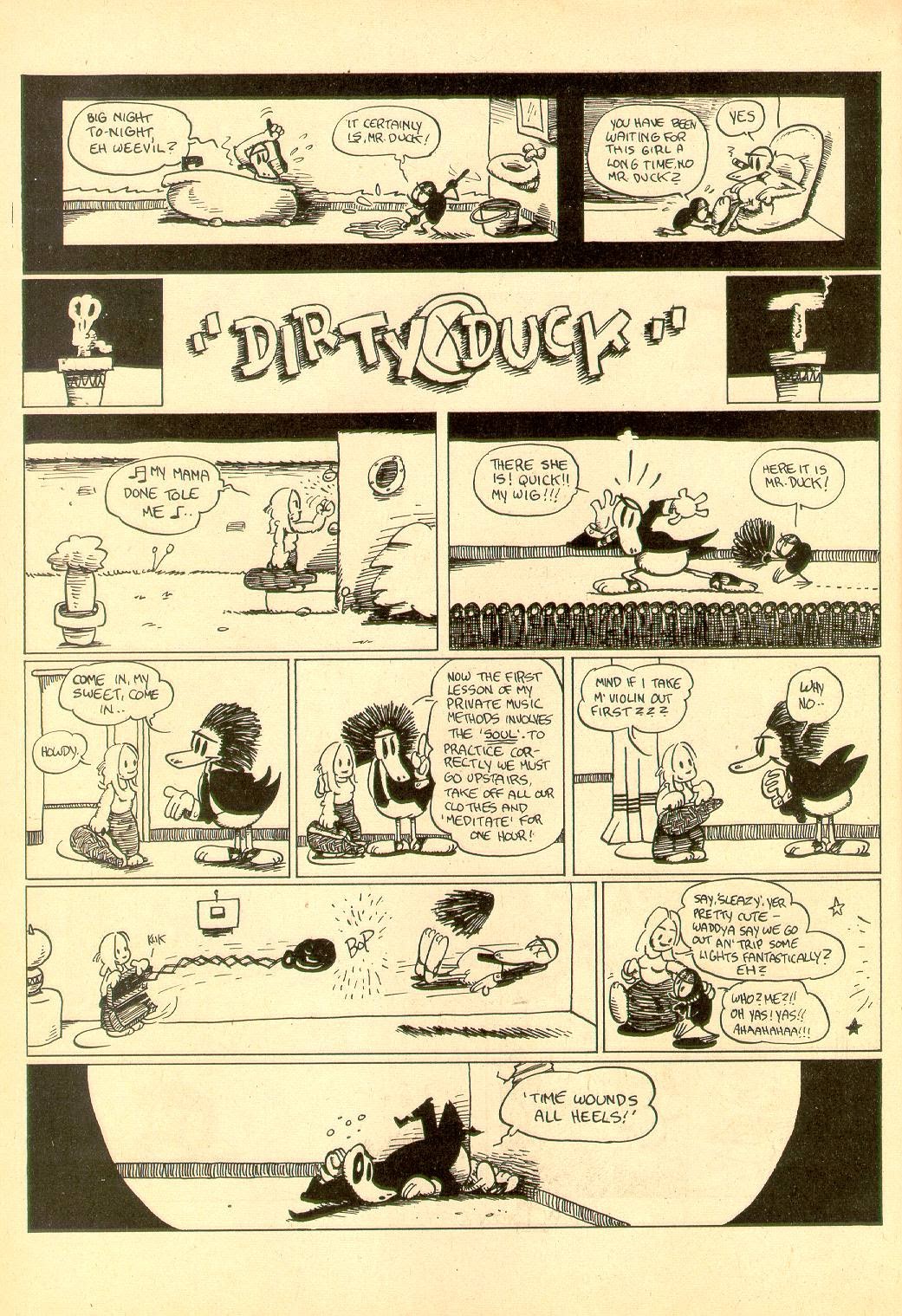

A “Dirty Duck” strip by Bobby London. From Air Pirates Funnies #1, July 1971, Last Gasp.

Art from “Tomb of the Space Gods” by Alexis Ziritt; from Space Riders #3, June 2015 by Alexis Ziritt (artist), Fabian Rangel, Jr. (writer), and Ryan Ferrier (letterer)Rory Hayes. Published by Black Mask Studios.

Art/text attributed to “Marks.” Back cover of Mother’s Oats Comix #2, August, 1971, Rip Off Press.

![]()

From “The Creature in the Tunnels” by Rory Hayes. Published in Bogeyman Comics #1, 1969, Twelve A.M. Publications.

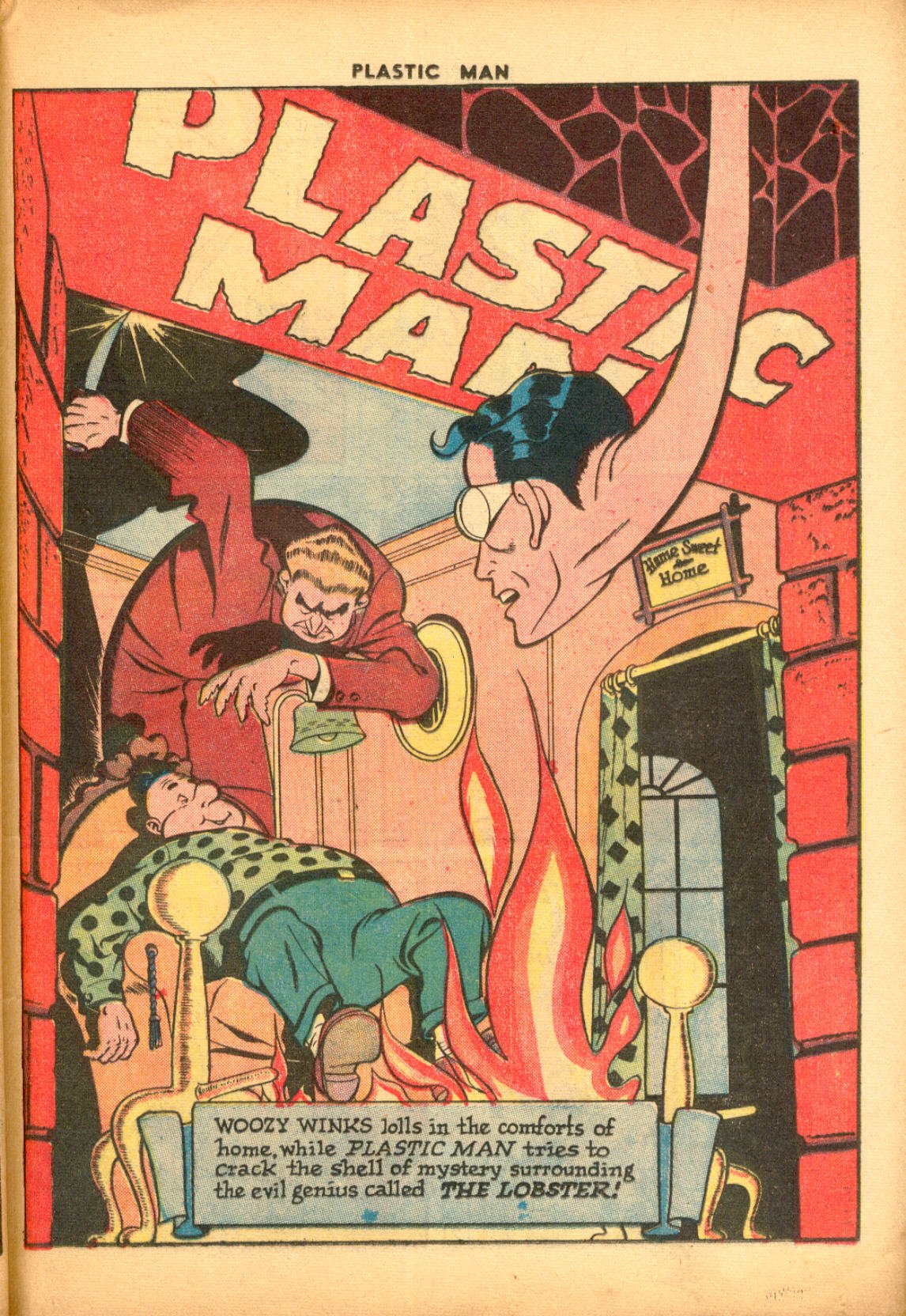

From “The Lobster” by Jack Cole, Plastic Man #4, July 1946, Quality Comics.

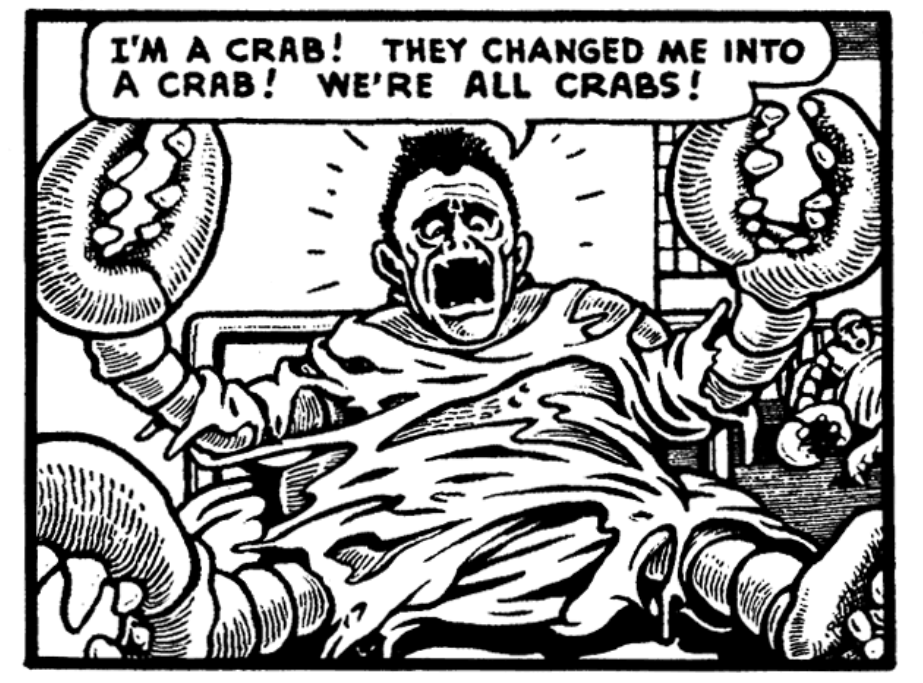

From “They Crawl by Night” by Daniel Keyes and Basil Wolverton, Journey Into Unknown Worlds #15, February 1953, Atlas Comics. Reprinted in Basil Wolverton’s Gateway to Horror #1, June 1988, Dark Horse Comics.

From “Lost in the Andes!” by Carl Barks, Four Color Comics #223, 1949.

From “The Paradox Man, Ch. 2” by Barry Windsor-Smith, Storyteller, 1996

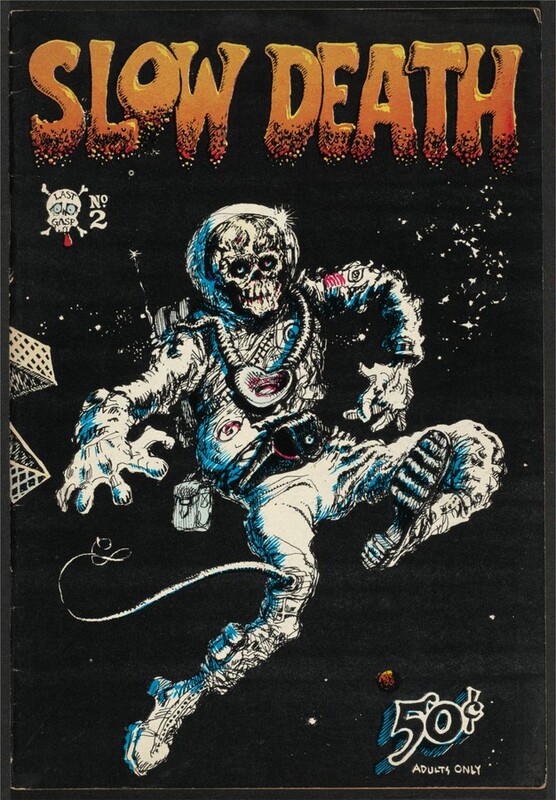

Cover for Slow Death #2, 1970 by Jack Jackson and Dave Sheridan

From “A Folk Tale” by Gilbert Hernandez, Love and Rockets #27, 1982

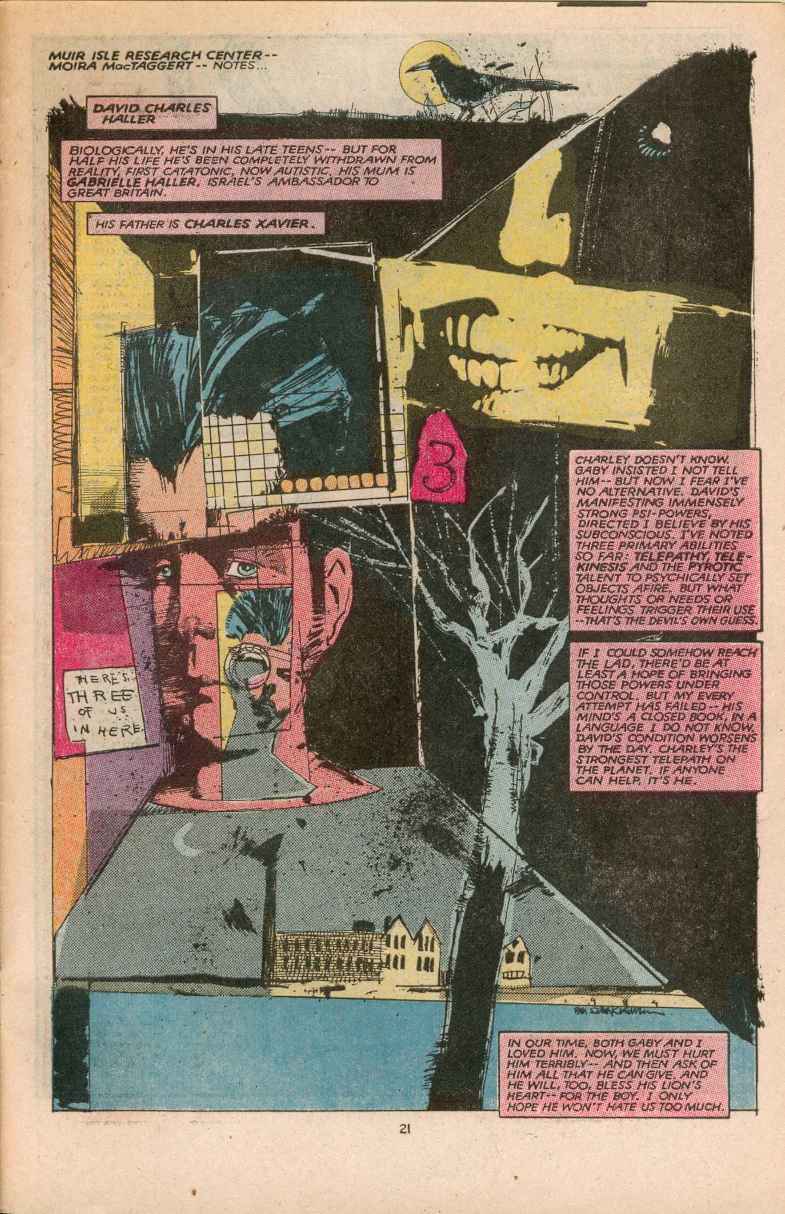

From New Mutants #25, 1985 by Bill Sienkiewicz and Chris Claremont

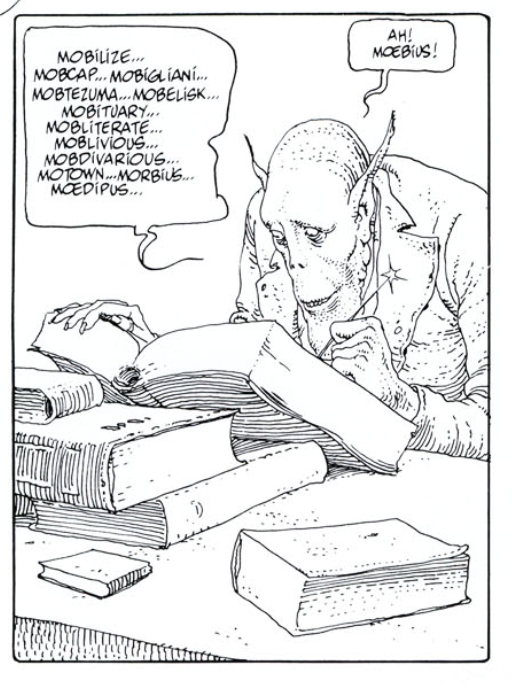

From Moebius’s illustrations for Robert Bloch’s Contes de Terreur, 1975; reprinted in Metallic Memories, 1992.