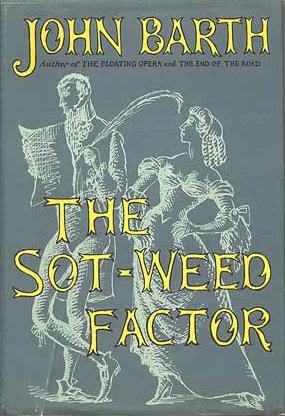

I finished the audiobook version of John Barth’s novel The Sot-Weed Factor last week. I’d tried to read the novel a few times in the past, never getting past page 56 of my Bantam mass market edition, which runs to 819 pages. That’s a long book. The unabridged audiobook runs just over 36 hours. That’s a long time. Too long, really, for what Barth has to offer here, but before I get into that, I’ll give a tip of the hat to the excellent production values and the wonderful voice talent of Geoffrey Centlivre, who is by turns expressive, wry, pathetic, bathetic, or understated, depending on what Barth’s prose calls for. He understands the novel and does an estimable job translating it.

The Sot-Weed Factor enjoys the reputation of being Barth’s finest work (although let me just go ahead and disagree with this generalized assumption that I’ve attributed to no one in particular and say up front that the novel is ultimately a boring overlong drag and anyone interested in Barth is better off starting with Lost in the Funhouse). The novel parodies a number of literary styles — Bildungsromans, picaresques, Künstlerromans, adventure stories, histories, romances, and serialized narratives in general. Adopting the language (diction, tone, syntax, form and all) of 17th century prose, Barth tells the story of Ebenezer Cooke, a real historical figure whose 1708 poem “The Sotweed Factor, or A Voyage to Maryland, A Satyr” is considered by some literary historians to be the first American satire.

Barth’s Ebenezer is an innocent soul à la Voltaire’s Candide (hero of another picaresque that has the decency to be funnier, sharper, and, ahem, much, much shorter), a would-be poet whose spurious claims to being “Poet Laureate of Maryland” come constantly under fire. Ebenezer attributes his artistic powers (which are dubious at best) to the metaphysical virtue of his virginity; one of the major conflicts of the plot of The Sot-Weed Factor is poor Ebenezer defending his cherry from the various whores and ne’er-do-well who populate the book. And there are a lot of these whores and ne’er-do-wells: rascals and pirates and pimps and thieves and slavers and sluts of every stripe shuffle through The Sot-Weed Factor, underscoring several of Barth’s themes — innocence versus experience, perception versus reality, virtue versus vice, and stability versus flux.

In my reading, this last theme — the instability of identity, particularly American identity — is the major thrust of The Sot-Weed Factor. But before going into this idea, I suppose I should share at least some of the plot, or at least try to summarize it, which is almost impossible, as it shifts and slants and reverses in every chapter. In the interest of making a (very) long story short, dear reader, and making my job a bit easier, I’ll borrow from Don D’Ammassa’s summary (he’s got a great Barth page for those inclined)—

The story is set during the 17th Century. Ebenezer Cooke is the son of a well-to-do British gentleman who owns property in the Maryland colony in the New World. Ebenezer and his sister are tutored by Henry Burlingame until his sudden dismissal while they are in their late teens. Ebenezer is sent off to boarding school, where he finds it difficult to form a bond between himself and his environment, eventually retreating into poetry. He is also afflicted by an extreme form of indecisiveness in which he is literally frozen in place, some times for hours on end, incapable of making a decision. His abstraction from the world is reminiscent of Jacob Horner and Todd Andrews, although exaggerated even further.

The plot grows rapidly more complicated. Ebenezer is apprenticed in London, where he fails to prosper. He becomes infatuated with a prostitute, despite his own militant virginity; his poor prospects are then conveyed to his father, who ships him off to the family holdings in the colonies. Ebenezer decides to request a commission from Lord Calvert, governor of Maryland, to become its official Poet Laureate, believes that he has been awarded that honor, and sets out for the new world. In the course of that journey, he rediscovers Henry Burlingame, who has taken on another identity, is kidnapped by pirates, walks the plank, and eventually reaches land.

The complexity and twisted humor that ensue cannot be adequately described in a few words. Secret identities are revealed, coincidences flourish, absurd situations follow in rapid sequence. Ebenezer is honored and disgraced, is captured by angry natives and threatened with death. He discovers pieces of a secret journal of the adventures of John Smith and Pocahontas, and helps Henry Burlingame discover the truth about his own origins. There is considerable bawdy content, much of it surrounding the mysterious process by which John Smith managed to sexually satisfy Pocahontas.

I’m impressed with D’Ammassa’s concision here—he neatly puts together the major elements of a sprawling, fat novel. As you may see from D’Ammassa’s summary, The Sot-Weed Factor is all about the instability of place, the lack of solid ground in swampy Maryland, the discontinuity of historical narrative, the inability of art to overcome reality, and the rapid reversals of fortune and identity that might occur in a New World. It’s all “assy-turvy,” to use one of the character’s terms. The Sot-Weed Factor here shows its post-modern bona fides; there’s a constant inconstancy, a doubling of people, places, things, and then a trebling. Ebenezer’s Old World romantic virtues—his insistence on the metaphysical value of his virginity and the power of his feeble poetry—are not just contested but obliterated (only poor Eb’s too blind to see this). Barth reworks American history, dismantling and satirizing the Pocahontas narrative, and emphasizing the plight of the native Americans, enslaved Africans, and indentured Europeans in this brave new world.

The book is also a dismantling of literary history, a jab at metaphysical poetry and identity narratives like Tom Jones or the work of Dickens. While Ebenezer spouts the loftiest supplications to his airy muse, Barth keeps his humor stuck sloppily in the toilet. The Sot-Weed Factor surpasses any ribald work I’ve ever read. The book is larded with dick jokes, fart jokes, jokes about diarrhea, jokes about sex and venereal diseases and so on—it culminates with (as D’Ammassa points out above) a riff on 17th century Viagra. In short, Bath focuses most of his keen literary powers on the kind of sophomoric japes that might keep Bevis and Butthead’s attention. Again, it’s all “assy-turvy.”

Barth’s toilet humor is at times funny, but it becomes tiresome over the book’s long duration, especially when it’s often the sole reward for long expanses of poorly-conceived exposition. I found myself bored to tears at times listening to The Sot-Weed Factor, and had to force myself to continue in its final third, a challenge that became easier when the narrative finally picked up a bit. Just a bit though. The book’s major problem is not its bloat though, or its saggy exposition, or even its redundant fart jokes. No, these feel more a symptom than a cause, and I think they are symptom of a too self-satisfied (or self-satisfying) author; over its 800+ pages (or 36+ hours), The Sot-Weed Factor reveals itself as the literary equivalent of a very bright writer jacking off to his own research. In what must be the worst case of unrestrained writing I’ve ever seen (or heard, I suppose), Barth allows two of his characters, catty women arguing, one English, one French, to trade insults with each other, all various euphemisms for “whore.” This process goes on for minutes in the audiobook version and for six goddamn pages in my Bantam edition and, like much of the details in this fat beast, does little or nothing to add to the narrative. It’s as if in his research Barth has dug up dozens and dozens of lovely little antiquated slurs and can’t bear to edit a single one. If the process rewards Barth, it does little for the reader.

But if literary diarrhea is the mode of the book, then I guess it mirrors one of The Sot-Weed Factor’s many rude motifs. Personally, I wish I had my time back. There’s great value in reimagining the origin of America (I think immediately of Terence Malick’s The New World or Toni Morrison’s A Mercy or even some of William Blake’s work), but Barth’s narrative seems too self-indulgent and unrewarding to make any real claims to democratic (or, if I’m feeling harsh, artistic) insight. Perhaps The Sot-Weed Factor is the kind of novel that remains indivisible from its form, and perhaps to a contemporary reader like me this form is just too flabby and flaccid to spark spirit. As I’ve tried to communicate here, Barth has a sharp intellect and he’s more than capable of performing a wry, wise, and often funny analysis of early American history. But he indulges too much in his own sophomoric games and winks too often at the reader. It’s amazing that such a long book could feel so hollow.