Is The Running Man a good film?

I have no idea, but I’ve watched it at least a dozen times in the past 20 years, and I’ll watch it again. The 1987 film is certainly not the singular artistic vision of a supremely gifted auteur; it is not well-acted; the set design is imitative at best and terribly cheesy at worst; the costumes are silly; the music sucks. But The Running Man is zany fun, not least of all because its clumsy satire of a society clamoring to be entertained at any cost is as relevant as ever. Ironically though, The Running Man’s satire inevitably reproduces the exact thing it aims to critique: a loud, violent, silly distracting entertainment.

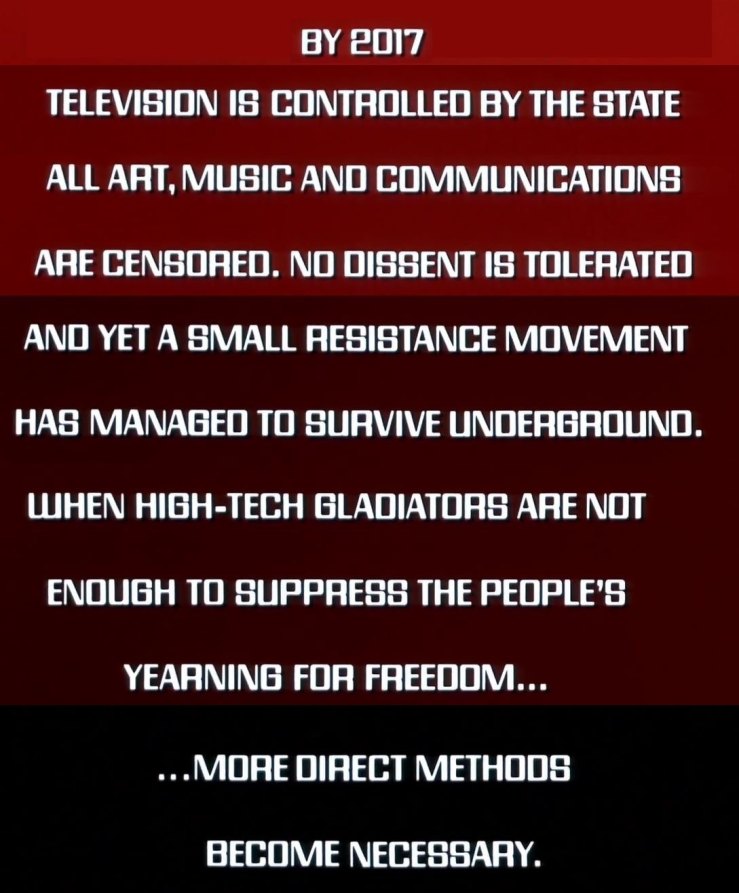

The Running Man foreground’s its plot in a (now retro-)futuristic font scroll at the film’s outset:

Those “high-tech gladiators” (dressed in ridiculous outfits and bearing ridiculous names like “Subzero” and “Captain Freedom”) stalk “contestants on a TV show called The Running Man. The show is hosted by Damon Killian, played by Richard Dawson (who you may know from reruns of Family Feud). Dawson fits into the film better than any other player—indeed his loose, improvisational, menacing charm is part and parcel of an entertainment empire built on attractive deception. He’s the consummate Master of Ceremonies, presiding over every aspect of his media empire. Dawson’s nemesis is Arnold Schwarzenegger, who plays Ben Richards, a former cop framed for a massacre. There’s a lot of fake news in Running Man, including an extended sequence of digital editing where faces are mapped onto body doubles. Schwarzenegger winds up on The Running Man, kills a bunch of stalkers, clears his name, and becomes a figurehead of the resistance.

Director Paul Michael Glasser (who played Starsky on Starsky and Hutch and later directed the Shaq-vehicle Kazaam) brings a workman-like approach to the film. His shots are often clumsy, and moments that should telegraph horror often come off as funny or just silly, as early in the film when a prisoner’s head explodes when he tries to escape a labor camp. Glasser makes no attempt to rein in Schwarzenegger’s ham. We get scenes where Schwarzenegger tries to imbue his character with a small measure of realism or pathos, and yet his mugging one-liners undercut any character building. He’s a cartoon of a cartoon, which is as it should be.

Schwarzenegger’s campy performance is balanced by María Conchita Alonso, who invests her foil Amber with a soul that belies the cheesy lines she’s forced to deliver. Alonso has the closest thing to a character arc in The Running Man, and arguably, she anchors the film—she’s a stand-in for the film’s viewer, a normal person who gets swept up into adventure. Yaphet Kotto also stars in The Running Man, but he’s woefully underused, perhaps because his acting is simply too good; his naturalism doesn’t mesh in the film’s campy tone. Other bit players work wonderfully though. Mick Fleetwood and Dweezil Zappa try to play it cool as resistance fighters, but the effect on screen is endearingly goofy. Mick Fleetwood would have been about 40 when the film came out, but he looks like he’s about 70…which is how old he is now. (There is a fan theory about this, of course). Dweezil wears a goddamn beret. The stalkers include professional wrestlers Professor Tanaka and Jesse “The Body” Ventura, professional wrestler and opera singer Erland Van Lidth De Jeude, and NFL great Jim Brown. Ventura apparently could not be restrained from eating the scenery around him. He twitches and snarls, and delivers his lines as if he were speaking to Mean Gene Okerlund. It seems if director Glasser simply let his actors play versions of themselves. This is reality TV, after all.

The real success of Glasser’s direction is, ironically, the limitations of his aesthetic vision. The film looks like a TV show, and indeed, the strongest shots approximate TV shows and their live audiences. The Running Man is at its best when blending its satire of cheap Hollywood elements into the film proper, as in the ludicrous reality TV clips interspersed throughout (like Climbing for Dollars), or in the repeated montages set to cheesy wailing keytar jams, featuring a troupe of sassy flash dancers, the camera ogling their buns of steel. Ironically too, the fight scenes between the stalkers and Schwarzenegger’s team are actually the dullest element of the film—they look like bad TV (which is basically what they are). The Running Man wants to satirize the way cheap entertainments distract a populace and cheapen human worth, but it uses the same tools as the cheap entertainments it wants to skewer.

The Running Man is about spectacle culture, and is hence larded with shots of crowds reacting to what they see on screens. The film’s viewer can see the silly crowds cheering the stalkers or booing Schwarzenegger or enjoying Dawson’s charms, but the viewer is also a spectator himself. In the words of Dawson’s Killian, the film strives to “give the people what they want” — which here means an uplifting ending—Viva La Resistance!—a zany horrific comedy that simultaneously critiques and condones our worst impulses And yet the resistance uses the same tools to defeat the oppressive entertainment empire—video editing designed for mass consumption by a spectacle society. It’s Pop Art without the “Art.”

The Running Man is slightly stupid, which is a great part of its enduring charm. Its greatest stupidity is in its attempts to be clever—but again, there’s the charm of it. It’s a film about Bad TV that actually looks and feels like Bad TV. The film is like the less-talented but affable little cousin of Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop, which came out the same year. Both films satirize an emerging media-driven dystopian culture, but Robocop is actually a good film. The Running Man winks a bit too much (in contrast to, say, 1989’s Road House, probably the best film I can think of that plays its satire so straight that it potentially confounds its viewers).

And yet for all its silly weaknesses and bad hyperbole, The Running Man’s prognosis of American culture is painfully accurate. Fake news, bad actors, a TV president, lives thoroughly mediated by media, degradation of the human condition as entertainment—the Omnipresent Screen as the Ultimate Authority. The Running Man‘s 1987 vision of the future seems more accurate than the future posited in the film I watched yesterday, 1984. And yet 1984 captures an emotional truth that The Running Man sets out to crush or gloss over or convert into something artificial, the idea or representation of a feeling, but not the feeling itself. That’s what entertainment does.

How I watched it: On a large television, via a streaming service, with semi-full attention.