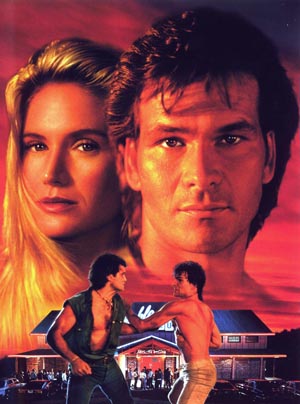

Twenty years after its release, Rowdy Herring’s neo-western Road House holds up better than ever. The film stars an iconic Patrick Swayze as a philosophical cooler named Dalton hired to clean up a road house bar. In this process, Swayze’s Dalton discovers that the small town is under the thumb of the bullying gangster Brad Wesley (played with zealous malice by Ben Gazzara). Dalton cleans up, kicking ass without bothering to take names, and leaving a not-unsubstantial body count. This short plot review in no way conveys the brilliance of this film, which can’t really be captured in words–Road House must be witnessed. You have to see the rampant brawling, hear the awesome dialog (sample: “Pain don’t hurt), experience the spectacle that is Road House. That said, not everyone can appreciate what’s going on here: it merits a 5.7 out of 10 at IMDB and a 42% at Rotten Tomatoes. In short, the film is divisive. In his original review of the film, Roger Ebert wrote, “Road House exists right on the edge between the “good-bad movie” and the merely bad. I hesitate to recommend it, because so much depends on the ironic vision of the viewer.” A careful reading of Ebert’s review reveals that he really enjoyed the film. “Was it intended as a parody?” he asks. “I have no idea, but I laughed more during this movie than during any of the so-called comedies I saw during the same week.”

Ebert’s question of intentionality is instructive (if not ultimately that important). Any savvy viewer–especially those with a fine-tuned sense of “ironic vision”–will have to ask herself whether director Rowdy Herring and his crew meant to create such a sublime parody, or if the resulting masterpiece is just a happy accident. The simple answer to the question is that it doesn’t really matter, of course, but I still find it a curious issue of aesthetics, especially in light of a new breed of action films that are particularly self-aware. These include Jason Statham’s Crank films (2006 and 2009), movies that ask the viewer to suspend any rudimentary understanding of physics in exchange for ninety-minute doses of adrenaline overdrive. I’ve actually just described most Statham vehicles, but it’s the knowingness of the Crank movies that make them such a joy: part of the joke is that the film recognizes its ludicrousness. The Cranks want to make sure that the audience gets that they get that the audience is getting what the films are getting at. 2007’s Shoot ‘Em Up, starring Clive Owen and Paul Giamatti operates on the same principle. Shoot ‘Em Up is a series of action set pieces so ridiculous that the phrase “over the top” doesn’t even begin to function as a critique (during one of the film’s many, many gun battles, Owen’s character delivers a baby and then cuts the umbilical cord by shooting it). In a sense, films like Shoot ‘Em Up and Crank operate outside of any normal critique, including not just visual cues but also dialog to announce their parodic intent (Giamatti’s villain exclaims that “Violence is one of the most fun things to watch,” at one point). This isn’t to say that it’s impossible to be critical of such films (it’s very, very possible, actually), just that the films incorporate a sort of generational “ironic vision” of their audience as part of the viewing experience.

Indeed, these films count their success on the audience’s ability to “get”–and appreciate–the irony being conveyed. While action films have long used irony and meta-fictional devices as part of their vocabulary, those devices have usually been an invitation to the viewer to deepen his or her fantastical identification with the film. 1993’s Schwarzenegger vehicle The Last Action Hero is a consummate example here; in this dreadful film an action hero comes to life at the behest of a young boy who becomes a surrogate for the audience. The meta-troping here isn’t so much ironic; rather, it’s just another reification of hero-spectacle-audience dynamics. Films like Shoot ‘Em Up and Crank, in contrast, ultimately disconnect the heroic-identification most traditional action movies strive for. This isn’t to say that the audience member’s ironic vision prevents him or her from living vicariously for 90 minutes through the hero (or, more accurately, anti-hero)–it’s just that the vicarious, distorted nature of the identification is always on display. Put another way, Shoot ‘Em Up, Crank, and other movies that fit this mold (these might include Tony Scott’s unfairly maligned 2005 film Domino, 2008’s Death Race, 2007’s Smokin’ Aces, and even Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror (although surely that particular film is a separate discussion)) invite their audiences to both revel in and mock the conventions of heroic narrative filmmaking. These films take place entirely within scare quotes; there’s no danger that their irony might be misinterpreted. Only the most callow of viewers will not “get” the intentionality of parodic irony here (contrast Ebert’s unconfused review of Shoot ‘Em Up with his questioning of Road House; there’s not a hint of nervousness that the silliness of the latter might be unintentional). These films wink so often at the viewer that the gesture becomes a distracting nervous tic.

While I have a certain fondness for the parodic, ironic action films I’ve mentioned, I have to admit that their greatest failure is, ironically, their defining characteristic. They announce their parodic content at all times, squashing any of the anxieties about intention that a viewing of Road House engenders, and, in doing so, they lose an unqualifiable, unquantifiable joy. The greatest parodies never announce themselves as such, and thus create a contradictory balance of trust and anxiety from savvy viewers. In my estimation, no one does this better than director Paul Verhoeven, auteur behind Robocop, Starship Troopers, and Showgirls. Verhoeven’s films are doubly generous: on one hand, they function beautifully as straightforward Hollywood fare; on the other hand, with the assistance of a particular ironic vision, they are brilliant satires of not just culture and politics, but also of the very art of filmmaking and the implicit contract between film and audience. In contrast with the studied irony of certain latter day action movies, the films of Verhoeven don’t blink, let alone wink at their audience, making the irony that much more delicious. Road House, without the benefit of a director with the oeuvre of Verhoeven, is certainly one of the most quizzical documents of the late eighties. Is the film self-aware? Swayze’s winning performance gives nothing away, allowing the audience to fully identify with his rampant bad-assery. There is no simple answer to the question the film must prompt to any contemporary viewer, just as it did to Ebert in 1989: “Is this for real?” It’s that anxiety of indulgence, of undecidability, this central ambiguity that makes Road House such a joy to watch. The film does not force you to watch it through any particular ideological lens. Celebrate Road House‘s 20th anniversary by giving it a proper re-viewing; whether you bring your ironic vision is up to you.

[…] Week continues at Biblioklept. Road House (read my essay!) is one of my favorite films of all time). Share this:Like this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

LikeLike

[…] My gut feeling, which might be entirely wrong, is that Spring Breakers is an expensive prank, a film shot entirely in ironic quotation marks that the viewer will never see because Korine will never call attention to them. (This potentially puts Spring Breakers in the same territory as masterpieces like Road House and RoboCop). […]

LikeLike