What seems to’ve begun happening out here on the route with some regularity is that impulses disallowed in normal society are surfacing unexpectedly and being acted upon. Some more benevolent than others, spontaneous pig rescue, for example.

Unaccustomed bustle one day in the repair shop, where the ill-tempered Sándor Zsupka, across whose path few who have ever ventured care to do so again, currently on the run from a number of felony charges, including actual bodily harm, is putting together a pig-customized helmet and goggles combination revealing along with his criminal activities a gift for millinery.

“This is your…”

“Spirit guide, and even a spirit guide can do with some extra windproofing now and then. Further questions?”

“Never seen a pig quite like this…”

She’s a Mangalica, a popular breed in Hungary at the moment, curly-coated as a sheep, black upper half, blonde lower. And that face! One of the more lovable pig faces, surrounded by ringlets and curls. Squeezita Thickly should only look half this adorable.

No more than idly cruising the countryside, Sándor happened to get off on one of those fateful back roads, and there in a steep farmyard were a family and their livestock, a cute meet, you’d say, though not half as cute as the pig herself. “Oh and this is Erzsébet, we’re eating her for Christmas.”

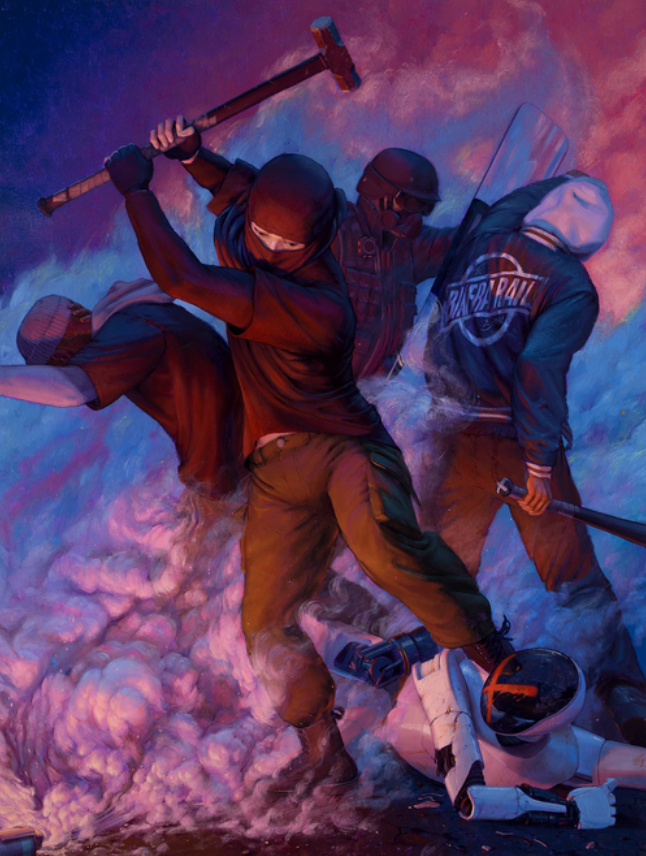

Hell they are. Sándor and some barroom accomplices perform a snatch-and-grab in the middle of the night, the pig pretending to be asleep, as she is picked up, installed in the sidecar of Sándor’s rig, and spirited away, just like that. Next thing anybody knows she’s riding in the sidecar, done up in helmet and goggles, beaming, posing like a princess in a limousine. Anybody feels like commenting, they don’t.