1. I got a Kindle Fire for Christmas this year, and have been using it for about a month now. I’m not sure how to go about “reviewing” this product, so I’m going to riff a bit.

2. Let’s get the whole Amazon-as-Evil-Empire thing out of the way up front: Yes, Amazon’s business practices are unsavory; yes, attempting to decimate the publishing industry as it currently exists is Not Good; yes, their practices threaten brick-and-mortar stores (the kind that actually pay local and state taxes!); yes their practices work to undermine key figures in the publishing industry—y’know, people like editors.

3. Picking up on that last clause: self-publishing (and the self-publishing “revolution” that e-readers like the Kindle Fire entail) may seem fine and dandy cotton candy, but there’s a reason that editors (and publishers and publicists, etc.) exist. These people make books better. These people make books. (And no, by the way, I’m not interested in reading your self-published ebook, so quit sending me email blasts).

4. Seems like I’m riffing out a lot of context, so let’s keep going: Perhaps you read whinypants Jonathan Franzen decrying the impending moral failures/societal breakdown that will result from ebooks replacing print editions. Franzen’s position is, of course, reactionary and conservative, and deeply rooted in the fear that the perfect Platonic permanence of books will be subverted or decimated.

5. Franzen’s reaction is rooted in part against a (common, teleological, utopian) misconception about the longevity and stability of digital content. Simply put, many people are operating under a dramatic misunderstanding of just how unstable digital content is. Where will all these books be stored, and in what format? Who will be responsible for archiving these materials?

6. A simple thought experiment, germane to item 5 above: Think back on all the obsolete media that you have used in your lifetime. I am in my thirties; my list would include cassette tapes, VHS tapes, laser disks, floppy disks, minidiscs, CDRs . . . (I don’t include vinyl records in this list. I still own hundreds of them and play them regularly).

7. To recontextualize: Printed books are a far more stable format than ebooks.

8. To wit: Ursula LeGuin in her essay “Staying Awake” from a 2008 issue of Harper’s:

The book itself is a curious artifact, not showy in its technology but complex and extremely efficient: a really neat little device, compact, often very pleasant to look at and handle, that can last decades, even centuries. It doesn’t have to be plugged in, activated, or performed by a machine; all it needs is light, a human eye, and a human mind. It is not one of a kind, and it is not ephemeral. It lasts. It is reliable. If a book told you something when you were fifteen, it will tell it to you again when you are fifty, though you may understand it so differently that it seems you’re reading a whole new book.

9. Points 2-8 seem like so much hemming and hawing, so much reticence to discuss what I seemed to promise at the outset: Some sense of what reading on the Kindle Fire is like.

10. Some things I like very much about reading on the Kindle Fire:

It creates its own light for night reading.

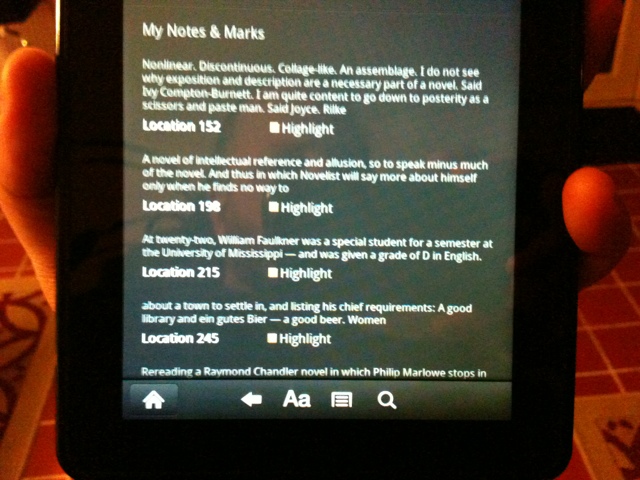

It’s easy to highlight and annotate passages (and then open up a new screen to look at just those highlights and annotations, isolated from the text proper).

It’s lightweight and ergonomic and, when I read with it over my head, my wrists don’t constrict and go tingly.

It holds a lot of books.

11. Some things I like about the Kindle Fire that I would think I wouldn’t like about the Kindle Fire, were I to read such a list from another person:

I can determine how far I have read into a book as a percentage.

I can stop and browse the internet in the middle of reading.

I can look up words or even wikis as I go by simply hovering a finger over a word or phrase.

12. My daughter loves the thing. Loves loves loves it. She is probably the primary user. She is four and a half. I think the interactive books she adores are marvelous.

13. Some things I don’t like about the Kindle Fire:

No book smell.

One texture for all books: This is probably the biggest problem I can see with the Kindle Fire.

It requires a battery charge, so there’s a built in level of accessibility; a sense that one must needs “prepare” ahead of time to read, perhaps (unlike our old friend the print book, which only requires a light source).

No bath time reading.

I can’t read it around my daughter, because she will attempt to take it, or, at minimum, curl up in my lap.

It is not possible to have like three or four books open at once.

Can’t read .cbr files. Why? Why?

I had to buy a USB micro B cable to connect the Kindle to the computer that I use to store digital content. Why not include this cable, Amazon? (It’s almost as if the company wants consumers to be solely reliant on Amazon’s services as a content provider . . .)

14. I’ve found it nearly impossible to read an electronic book on the Kindle that I started as a print book. For example, I’m about half-way through Teju Cole’s novel Open City; the kind publicist who sent it to me also sent me an electronic version of the text. I began the print copy in earnest, but the other night, after reading a bit of Hawthorne on the Kindle, I found myself wanting to sink back into Cole’s Sebaldian orbit. When I found my place in the text though, I felt alienated, bleak even, as if I were not reading the definitive version of Cole’s book but instead its cheap ghost. There is no intellectual or objective justification for this feeling. Call it a vibe or a habit.

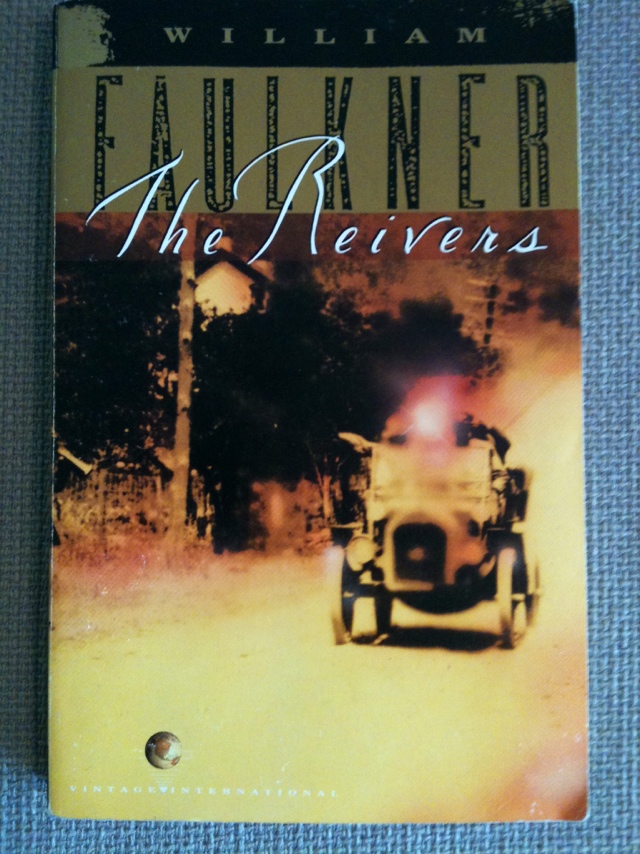

15. Books that I enjoy reading on the Kindle Fire:

David Markson’s The Last Novel, which perhaps begs to be read on such a device.

Anything by Nietzsche, but his aphoristic works especially.

A .pdf version of Luigi Serafini’s rare and expensive book The Codex Seraphinianus (one of many verboten tomes on my Kindle, but remember the name of this site if you please . . .)

Anything by Whitman, especially letters and other non-essentials that I would not normally pursue.

Ditto Hawthorne.

Ditto Dickinson.

Ditto Melville.

Oh, and beyond the overlooked and underfamous works of certain American Renaissance faves: Moby-Dick too, which seems looser, freer, more aphoristic on the Kindle. (Why?)

Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, which seems simultaneously dated and futuristic. Like William Gibson with a strong streak of Pynchonian sillies.

And Gibson: Rereading Burning Chrome. Had forgotten how good some of these shorts are.

Houellebecq’s Whatever: its brevity, its succinctness gels with my nascent Kindle habits, or perhaps instructs my Kindle habits, or more likely creates my Kindle habits.

16. To return to a point in #13 above: The Kindle Fire necessarily imposes a uniform texture on every book that one reads on it; this would be true of any e-reader. Sure, you can change the background (white, black, or a sepia color, which is what I prefer), fonts, sizes, spacing, etc. — but there is no sense of physicality, of individual identity, of, dare I say it, specialness, to the texts. I am aware that these are terribly subjective and overtly Romantic terms, but hell, I like physical books. I like their covers and their smells and their discolorations. I like leaving bookmarks in every book that I finish or abandon—I almost always find a new bookmark for every book that I read (the autobookmark on the Kindle is useful, but how can it compare with a photograph of my son or drawing by my daughter or a postcard from a stranger or a scrap of poetry from a discontinued textbook or an old grocery list of my wife’s from years before we were married?).

17. I titled this post “A Riff on the Kindle Fire,” but that’s a bit ambiguous I suppose: I did not compose the post on the Kindle Fire, which I find awkward re: blogging/wordprocessing. I used a laptop (with some help from an iPhone). Maybe the preposition “about” would be more suitable.

18. By way of closing, after four weeks with the thing:

It’s light.

It’s convenient for night reading, but you probably shouldn’t take it in the bath.

No book smell.