We have the right to convey the fictive of any reality at all–and there is nothing that is not real—by any method we wish, and to have as our goal, if we so opt, only that we maintain the reader’s tension, the solitary indication, itself mercurial, of a work-of-art event.

Syntax being nothing more nor less than the codification of selected usages, we may alter syntax or reject it wholly.

We may compose the fictive in such a manner that the result is ambiguous, baffling and sometimes altogether impossible significantly to paraphrase-but so long as the piece seizes and holds the reader, a basic meaning, impossible to state in language as we know it, has been established, a meaning that belongs to a time series of seizing-and-holding.

The notion, we submit, of clarity, remains simply a notion, real enough, of course, under whatever category it is sub-sumed, but of no universal vigor, necessarily, nor marked by socalled objective truth; clarity is a notion identifying a particular social agreement in a one-to-one sense as to what construct evokes similarity of analysis.

Empirically all that is demonstrable is that we experience as creator or audience a series of perceptions. Now, if we set forth that demonstration in the fictive in such a fashion as to generate and sustain tension in the reader whether or not he is mystified by the significs, we have met the sole possible criterion.

We are not of course here in any way concerned with the alleged scalar values of a given fiction-the notion of value belongs to ad hominen pleaders usually involved in depressing or elevating a status for economic reasons—just as we cannot in any way be concerned with the alleged scalar values of the given reader. Fiction and reader are conjoined, and may not with any sense be disjunct if we are trying to penetrate the nature of the esthetic.

Such being the case, I believe we can with some innocence look at the choices of the contemporary avant-garde herein, and digest them according to our lights or chiaroscuras.

We need remember only how much more we usually discern if we take the trouble, to begin with, to clean our own canvasses-within reason.

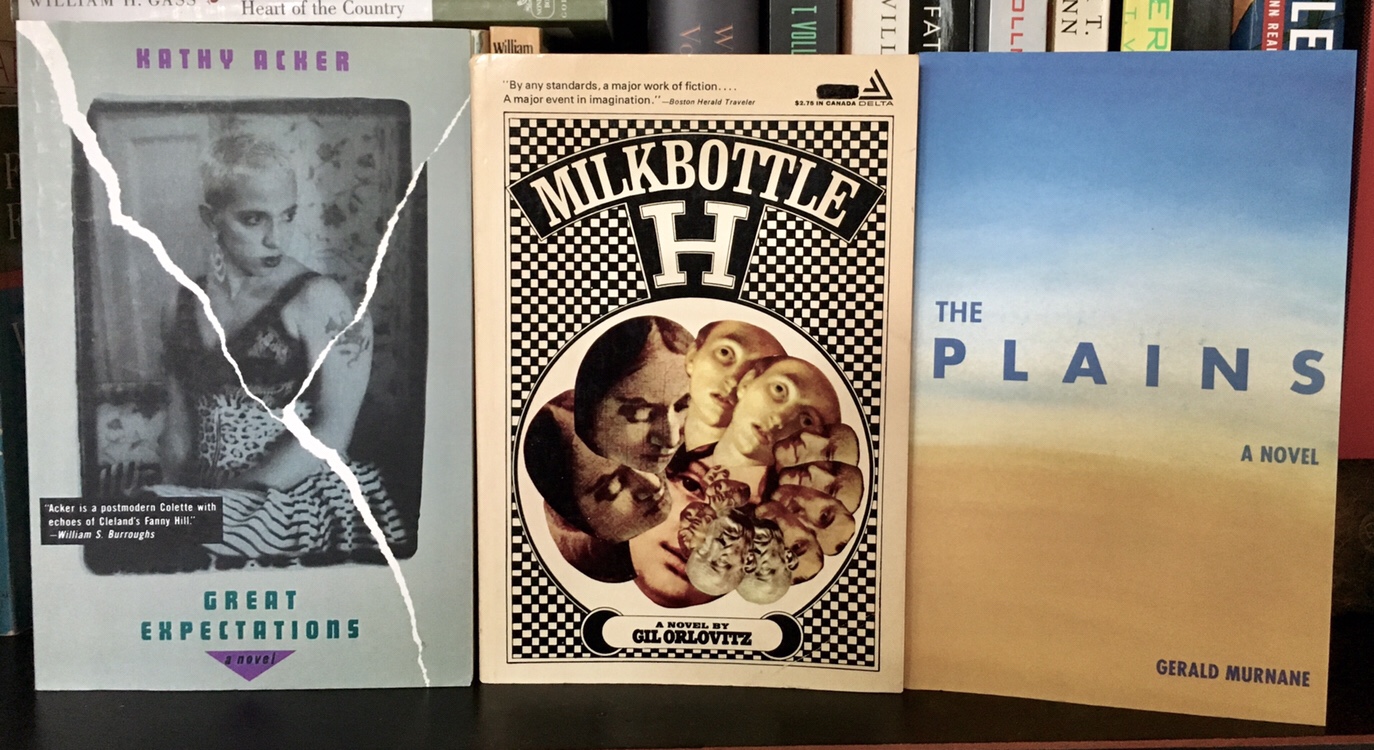

—Gil Orlovitz

Gil Orlovitz’s introduction to The Award Avant-Garde Reader (1965).