Hurricane Milton passed far enough south last night to leave our city relatively untroubled. There were power outages here but not the expected flooding. Most of my anxiety was focused on my family in the Tampa Bay area, all of whom are safe; we’re just not sure about the material conditions of the things they left behind.

Milton seemed to suck the summer air out of Northeast Florida; when I got out of bed and went outside to investigate the loud THUNK that woke me up at four a.m., I was shocked at how cold the air felt. It was only about 66°, but all the humidity seemed gone, even in the cold sprinkling rain. (The THUNK was our portable basketball hoop toppling over.)

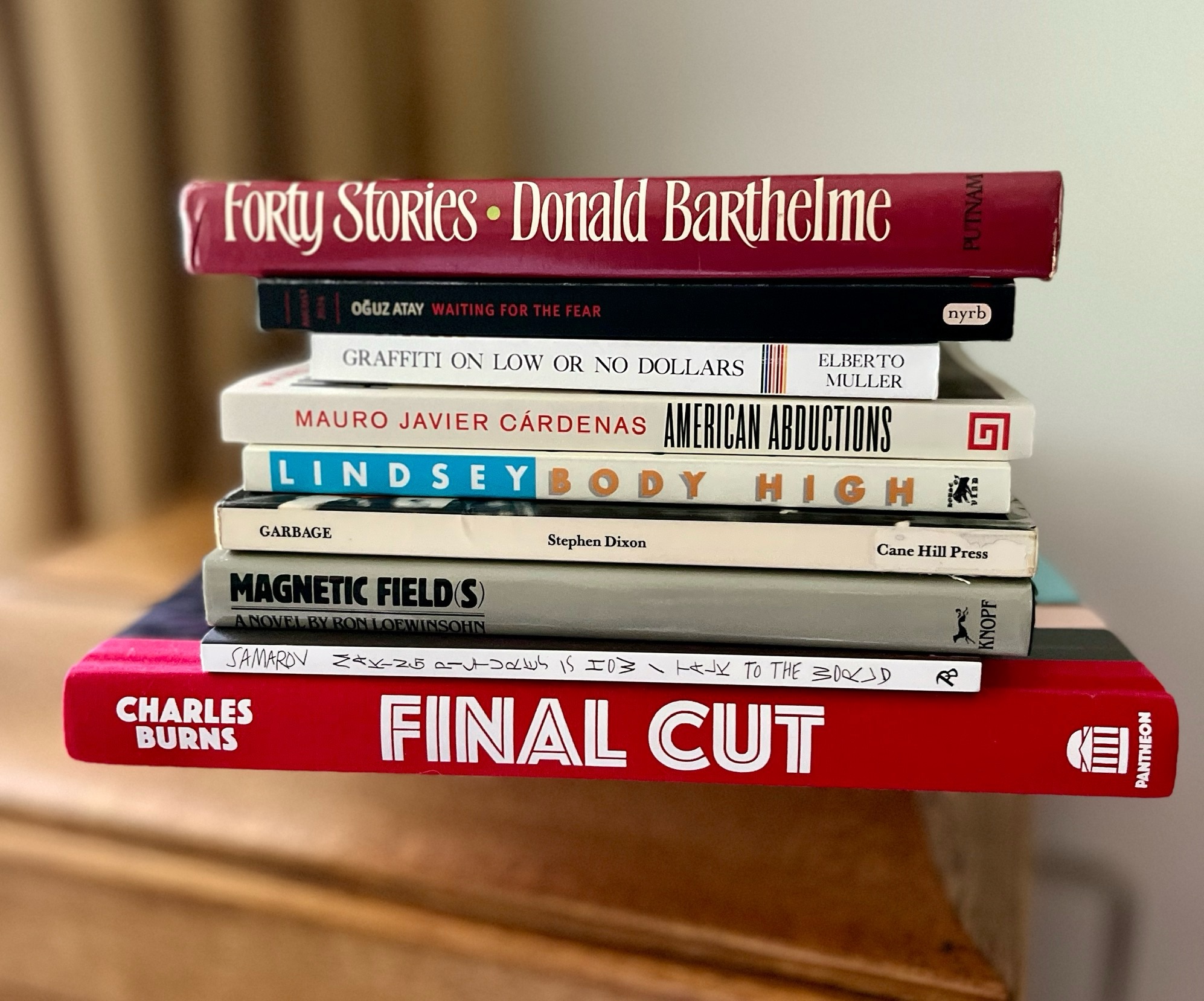

I thought I might try to knock out a review or a write-up of one of the many books I’ve finished that have stacked up as the summer has slowly transitioned to autumn. College classes have been canceled through to Tuesday. I have, ostensibly a “free” week; maybe some words, harder to cobble together for me these days, would come together, no? For the past few years I’ve focused more on reading literature with the attempt to suspend analysis in favor of, like, simply enjoying it. I realized I’d gotten into the habit of reading everything through the lens of this blog: What was I going to say about the book after reading it? I’ve been happier and read more sense freeing myself from the notion that I need to write about every fucking book I read. But the good books stack up (quite literally in a little place I have for such books); I find myself simply wanting to recommend, at some level, however facile, some of the stuff I’ve read. So forgive this lazy post, organized around a picture of a stack of books. From the top down:

Forty Stories, Donald Barthelme

A few years ago, I read Donald Barthelme’s collection Sixty Stories in reverse order. A few days ago, a commenter left me a short message on the final installment of that series of blogs: “Now do Forty Stories.” I think I have agreed–over the past week I’ve read stories forty through thirty-five in the collection. More to come.

Waiting for the Fear, Oğuz Atay; translation by Ralph Hubbell

A book of cramped, anxious stories. Atay, via Hubbell’s sticky translation, creates little worlds that seem a few reverberations off from reality. These are the kind of stories that one enjoys being allowed to leave, even if the protagonists are doomed to remain in the text (this is a compliment). Standouts include “Man in a White Overcoat,” “The Forgotten,” and “Letter to My Father.”

Graffiti on Low or No Dollars, Elberto Muller

Subtitled An Alternative Guide to Aesthetics and Grifting throughout the United States and Canada, Elberto Muller unfolds as a series of not-that-loosely connected vignettes, sketches, and fully-developed stories, each titled after the state or promise of their setting. The main character seems a loose approximation of Muller himself, a bohemian hobo hopping freights, scoring drugs, and working odd jobs—but mostly interacting with people. It kinda recalls Fuckhead at the end of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son (a book Graffiti spiritually resembles) praising “All these weirdos, and me getting a little better every day right in the midst of them.” Muller’s storytelling chops are excellent—he’s economical, dry, sometimes sour, and most of all a gifted imagist.

American Abductions, Mauro Javier Cárdenas

If I were to tell you that Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s third novel is about Latin American families being separated by racist, government-mandated (and wholly fascist, really) mass deportations, you might think American Abductions is a dour, solemn read. And yes, Cárdenas conjures a horrifying dystopian surveillance in this novel, and yes, things are grim, but his labyrinthine layering of consciousnesses adds up to something more than just the novel’s horrific premise on its own. Like Bernhard, Krasznahorkao, and Sebald, Cárdenas uses the long sentence to great effect. Each chapter of American Abductions is a wieldy comma splice that terminates only when his chapter concludes—only each chapter sails into the next, or layers on it, really. It’s fugue-like, dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish. It’s also very funny. But most of all, it’s a fascinating exercise in consciousness and language—an attempt, perhaps, to borrow a phrase from one of its many characters, to make a grand “statement of missingnessness.”

I liked Jon Lindsey’s debut Body High, a brief, even breezy drug novel that tries to do a bit too much too quickly, but is often very funny, gross, and abject. The narrator, who telegraphs his thoughts in short, clipped sentences (or fragments cobbled together) is a fuck-up whose main income derives from submitting to medical experiments. He dreams of scripting professional wrestling storylines though, perhaps one involving his almost-best friend/dealer/protector/enabler. When his underage-aunt shows up in his life, activating odd lusts, things get even more fucked up. Body High is at its best when it’s at its grimiest, and while it’s grimy, I wish it were grimier still.

Garbage, Stephen Dixon

I don’t know if Dixon’s Garbage is the best novel I’ve read so far this year, but it’s certainly the one that has most wrapped itself up in my brain pan, in my ear, throbbed a little behind my temple. The novel’s opening line sounds like an uninspired set up for a joke: “Two men come in and sit at the bar.” Everything that unfolds after is a brutal punchline, reminiscent of the Book of Job or pretty much any of Kafka’s major works. These two men come into Shaney’s bar—this is, or at least seems to be, NYC in the gritty seventies—and try to shake him down to switch up garbage collection services. A man of principle, Shaney rejects their “offer,” setting off an escalating nightmare, a world of shit, or, really, a world of garbage. I don’t think typing this description out does any justice to how engrossing and strange (and, strangely normal) Garbage is. Dixon’s control of Shaney’s voice is precise and so utterly real that the effect is frankly cinematic, even though there are no spectacular pyrotechnics going on; hell, at times Dixon’s Shaney gives us only the barest visual details to a scene, and yet the book still throbs with uncanny lifeforce. I could’ve kept reading and reading and reading this short novel; it’s final line serves as the real ecstatic punchline. Fantastic stuff.

Magnetic Field(s), Ron Loewinsohn

I ate up Loewinshohn’s Magnetic Field(s) over a weekend. It’s a hypnotic triptych, a fugue, really, with phrases sliding across and through sections. We meet first a burglar breaking into a family’s home and learn that “Killing the animals was the hard”; then a composer, working with a filmmaker; then finally a novelist. Magnetic Field(s) posits crime and art as overlapping intimacies, and extends these intimacies through imagining another life as a taboo, too-intimate trespass.

Making Pictures Is How I Talk to the World, Dmitry Samarov

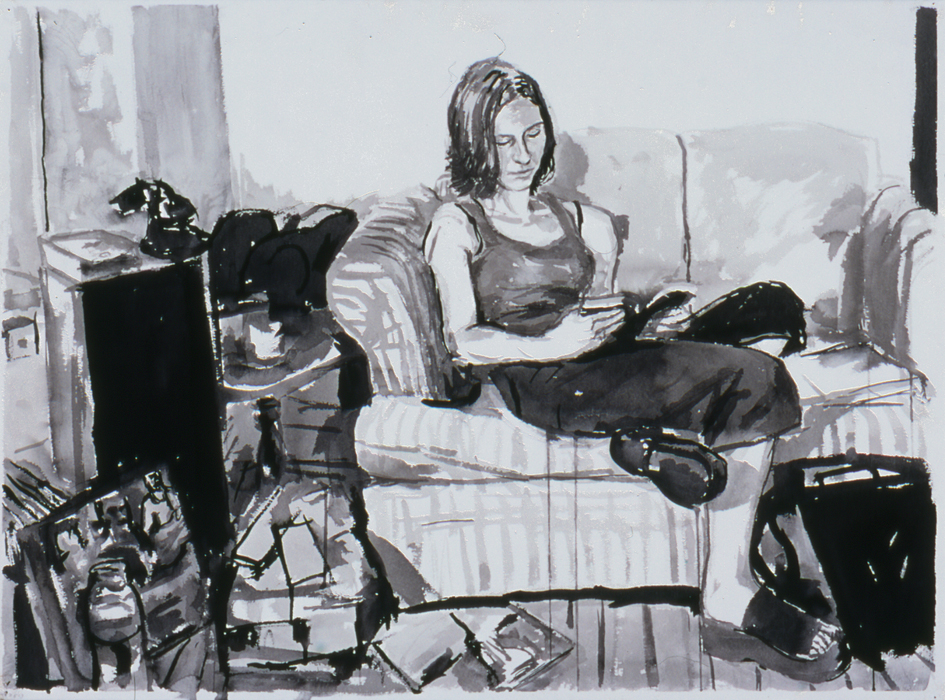

Making Pictures spans four decades of Samarov’s artistic career. Printed on high-quality color pages, the collection is thematically organized, showcasing Samarov’s different styles and genres. There are sketches, ink drawings, oils, charcoals, gouache, mixed media and more—but what most comes through is an intense narrativity. Samarov’s art is similar to his writing; there isn’t adornment so much as perspective. We get in Making Pictures a world of bars and coffee shops, cheap eateries and indie clubs. Samarov depicts his city Chicago with a thickness of life that is better seen than written about. Some of my favorite works include interiors of kitchens, portraits of women reading, and scribbly but energetic sketches of indie bands playing live. What I most appreciate about this collection though is that it showcases how outside of the so-called “art world” Samarov’s work is–and yet this is hardly the work of a so-called “outsider” artist. Samarov trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and yet through his career he has remained an independent, “not associated with an institution such as an art gallery, college, or museum,” as he writes in his book.

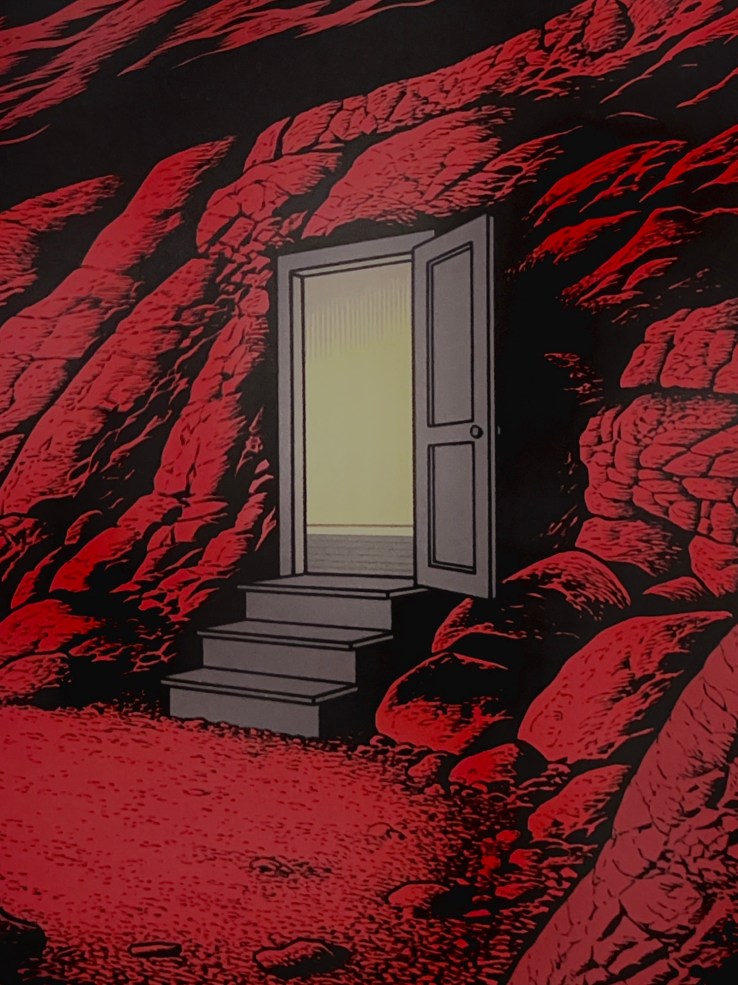

Final Cut, Charles Burns

I don’t know anything about Charles Burns’s upbringing, his youth, his personal life, and I don’t mean to speculate. However, it’s impossible not to approach Final Cut without pointing out that for several decades he’s been telling the same story over and over again—a sensitive, odd, artistic boy who is out of place even among others out of place. This is in no way a complaint—he tells the story with difference each time. And with more coherence. Final Cut is beautiful and sad and also weird enough to fit in neatly to Burns’s oeuvre. But it’s also more mature, a mature reflection on youth really, intense, still, but without the claustrophobia of Black Hole or the mania of his Last Look trilogy. There’s something melancholy here. It’s fitting that Burns employs the heartbreaking 1971 film The Last Picture Show as a significant motif in Final Cut.